After Steve by Tripp Mickle

/After Steve: How Apple Became a Trillion-Dollar Company and Lost Its Soul

By Tripp Mickle

William Morrow, 2022

If readers encountering Wall Street Journal reporter Tripp Mickle’s new book After Steve: How Apple Became a Trillion-Dollar Company and Lost Its Soul can get past the whopper in right there in the title – the US Supreme Court notwithstanding, companies don’t have souls – they’re in for a reading experience that’s in equal measures fascinating and subtly soiling.

It’s tempting to rush in and exonerate Mickle himself, making vague comments about a reporter simply reporting, but that would be overly generous – he’s brought on a healthy share of criticism himself, eyes wide open. He looked at the changes brought to Apple’s management and stock value in the wake of the death of Steve Jobs in 2011, and he decided not only to dress those up in the language of apostolic succession but also to pick a side.

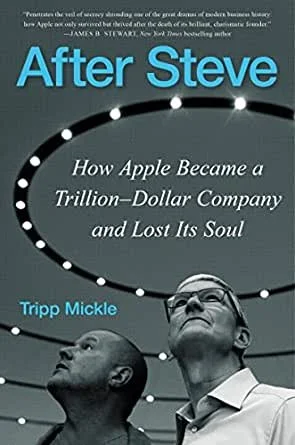

The two sides on offer are pictured on the US cover of the book: Tim Cook, Apple’s “king of commerce,” and Jony Ive, Apple’s visionary product designer. Ive was instrumental in the development of some of the company’s most iconic products, including the iPhone, the informal star of Mickle’s book. Cook was a company man, working his way up through the ranks until he stood at the right hand of Steve Jobs, trusted with the company as Jobs’s health failed.

Any hint that Jobs was a mean-spirited bully who leveraged the ideas of other people to make himself world famous is entirely absent from the narrative here; his divinity is taken as a given, as is Apple’s exceptional status as more of a cultural force than a corporation looking to maximize profits. And this rhetorical tactic very much extends to Mickle’s portrayal of Ive, whose foibles might be occasionally mentioned (a particular favorite: he ordered his Apple engineering team to drop everything in order to improve the soap dispensers on his latest private jet) but who’s consistently portrayed as pure-souled man-child in a world of, no pun intended, jobbing adults. “His seriousness at Apple events and at work concealed his tremendous sense of humor among friends,” readers are told at one point, and, hilariously, when U2 plays at a private party of his, we get non-ironic lines like this: “He then began to bounce up and down and sing along, as friends around him joined in, testifying to the fullness of life outside Apple.” U2 plays at your party, you sit on a throne during the proceedings, Barack Obama Skypes in his best wishes – yes indeed, it’s the little things.

The presentation of Cook is pointedly the opposite. Here, too, there are efforts to include sympathetic notes. When Cook sometimes visited the head office after Jobs’s death, we’re told that Cook “would push open the door and step inside to feel his predecessor’s presence. He compared those moments of reflection to visiting a grave site.” But the contrast is intended and hits like a metronome; the narrative leaves Ive happily dancing at a party and pivots immediately to Cook cozying up to the Trump administration.

And always, the book returns to that weird notion, the “soul” of a phone company. Gradually, over the course of many well-researched and sleekly-written chapters (no book on such a subject has any business being this wonderfully readable), Cook’s pragmatic, materialistic approach transforms Apple into a place where Ive feels like an alien, even though he’s never explicitly alienated by anybody. Cook’s approach works, Apple’s profits skyrocket, but Mickle has done such a skillful job in shaping his story that even in the midst of such Niagara gouts of money and burgeoning political power, readers might view these things as marks of failure rather than success. “Jobs’s presentations had enthralled people because they had been centered around it-just-works devices that were so intuitive that he had barely had to explain them. The magic had come from pulling them out of the box,” Mickle writes. “But Cook was introducing a financial construct, not a product.”

That’s where the soiling part breaks in throughout the book, the implication that this pallid Gradgrind sullied the non-financial “soul” of Apple by turning it into a multi-trillion-dollar company. This is the kind of Saint’s Life that’s only possible in a world of what online commenters refer to as “late-stage capitalism.” After Steve wallows in this kind of soteriological parsing, and that aspect of the book is purely revolting even though the book itself is tremendously enjoyable. True believers will finish it and gaze at their iPhones with renewed affection – until the new model drops.

-Steve Donoghue is a founding editor of Open Letters Monthly. His book criticism has appeared in The Washington Post, The American Conservative, The Spectator, The Wall Street Journal, The National, and the Daily Star. He writes regularly for The Boston Globe, the Vineyard Gazette, and the Christian Science Monitor. He’s a books columnist for the Bedford Times Press and the Books editor of Big Canoe News in Georgia, and his website is http://www.stevedonoghue.com.