Into the Breach: "Battle Royale" and "The Hunger Games"

/In the back of our ninth grade class, you may or may not recall, there sat a silent, studious boy whom everyone ignored. He wasn’t chubby enough to bully. He didn’t have the acne to scatter female cliques. Even the teacher, busy with students who achieved things or had problems, left him be. Such invisibility worked in his favor. Devoted to fictitious worlds, he wrote and drew continuously. Socials and first kisses, trivialities compared with the act of creating, only wrinkled his nose. His imagination, however, intensified, as he learned to focus it through the noisy social web of the surrounding classroom.

Outside school, cult cinema and underground comics educated the boy further. Their clever characters and violent plots invited interaction better than people did. And yet, bittersweet osmosis occurred. The boy couldn’t escape- not without dropping out- an upbringing steeped in teen drama as well as subversive pop culture. He soldiered through, taking notes. Had we realized? No. Thinking nothing of the boy’s inner life, we thrived in the angst-ridden realm as the queen bee, the super-jock, the teacher’s pet. We never reached out, never shared his enthusiasms.

So the boy hated us, one and all.

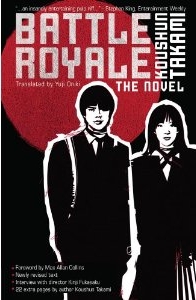

That’s one guess at the origin of Koushun Takami’s 1999 novel Battle Royale. A masterpiece of reptilian purity, it feels like an exploitation film more than anything you would find in a bookstore’s science fiction aisle. It has been translated into eight languages, and in 2000, the film version became one of Japan’s highest grossing ever, reaching $25 million.

The plot centers on 42 students, between fifteen and sixteen years old, who are trapped on an island. Their homeland, part of the Greater Republic of East Asia, is a successful fascist state where rock music is illegal, virtually nothing is imported, and “American Imperialists” are the enemy. More importantly, the public has conceded to a lottery that subjects teens to a brutal event called the Program. One student can leave the island, but only after he or she has survived the murder of the rest. Facilitating the mayhem are explosive tracking collars, exotic weapons, and 24 short hours. The purpose of such an exercise? To elicit terror, and eventually blind allegiance, from the populace.

If this sounds like the darkest horse among Japan’s plentiful pop exports, it is. Battle Royale has no galactic monarchies or spiky-headed ninjas. It has no giant lizards or demonic robots. The novel’s only outsized feature is its body count.

Takami was born in 1969. He missed Japan’s castration by the atomic bombs Little Boy and Fat Man. He missed the following decade of reconstruction, and the decade after that during which a liberal U.S. economic model proved Soviet communism to be the silliest of ventures. The boom years of his adolescence were uneventful. He walked the not-so-uniquely Western path to success: graduating Osaka University with a literature degree, and then abandoning a liberal arts correspondence course.

Still, one event from Takami’s youth, the Asama-Sanso hostage crisis of 1972, might have colored his writing. During the crisis, five members of the United Red Army trapped a woman in the lodge below Mount Asama, holding off police with gunfire for ten days. The final storming of the lodge was broadcast live on television for a (then) unprecedented ten hours and forty minutes. It resulted in two police deaths, but also the hostage’s rescue.

Ultimately, Asama-Sanso precipitated a massive drop in support for Japan’s leftist movements, which had grown and radicalized throughout the 1960s. In the film version of Battle Royale, we’re told that the Greater Republic of East Asia wants to suppress youth culture and encourage obedience. Further explanations appear in a prologue text, revealing a fifteen percent unemployment rate and the boycotting of school by 800,000 students.

On the eve of 1990, a 30 year-old Takami witnessed Japan’s bubble economy burst. The steep financial decline of the following two decades has been named the Lost Years. By 1991, however, Takami had begun his career with the news company Shikoku Shimbun, where he covered politics, police reports and economics, until 1996.

The idea of children slaying each other on an island should ring a bell, or better yet, pound a bongo drum. William Golding gave us Lord of the Flies in 1954, iconically presenting the theme that savagery lurked below our humanity, even among the most civilized. And because it is vibrant literature, Golding’s novel has permeated Western culture; there are two film versions, from 1963 and 1990; author William Butler’s 1961 novel The Butterfly Revolution, about a summer camp, is indebted to Golding; and the Simpsons have given homage to each novel, in the episodes Das Bus and Kamp Krusty.

But how to describe Battle Royale in the cultural continuum? As a novel, it clears the genre of literature with a moon-jump. Even as a fan, I insist that it lands in the hazy borderland between fiction thriller and smut. And as one reads to page twenty, then thirty, it becomes obvious that this was Takami’s intent. He sketches the bulk of his cast with dismissive speed:

At the front of the bus… was a group of noisy girls: Yukie Utsumi (Female Student No. 2), the class representative, looked good with braided hair; next to her was Haruka Tanizawa (Female Student No. 12), Yukie’s exceptionally tall volleyball teammate. Izumi Kanai (Female Student No. 5) was a preppy whose father was a town representative… They were the mainstream girls. You could call them the “Neutrals.”

Several pages of such paragraphs, and one thinks, “Yes, a lot of typical kids will soon die.” Which is never in doubt, because at the end of each of the first few chapters, we receive a clinical reminder that there are: 42 STUDENTS REMAINING.

That number drops quickly, once the students wake up in a classroom on the island. “I’ll kill you, you bastard,” screams a boy named Yoshitoki at their smug keeper, Sakamochi. From this page on, Takami establishes the pulpy tone that has made Battle Royale a cult classic:

…[the soldiers] resembled a chorus group, like the Four Freshmen. The men in fatigues… all lifted their right hands in a dramatic, emotionally charged pose. But their hands were holding guns.

Shuya saw Yoshitoki’s bulging eyes open even wider.

The three automatic pistols exploded all at once. Just as he was stepping out into the aisle, Yoshitoki’s body shook as if dancing the boogaloo.

We hardly knew Yoshitoki before his sight-gag of a death.

Naturally, Takami gives us a bit more on his ethical every-man protagonist, Shuya, and other primary characters, including Shinji, a trustworthy athlete with smarts to match; Kazuo, a gang leader known for making tough decisions without emotion; Noriko, the reluctant love-interest; and Shogo, an older boy, whose scars and too few words label him an unknown quantity.The problem is, Takami frequently robs himself of the grounding that would allow his characters to be sympathetic. Here is Shuya killing his first classmate during an accidental tumble:

Right above him, the hatchet was lodged into Tatsumichi’s face. Half of the blade stuck out from his face like the top layer of chocolate on a Christmas cake. The hatchet landed on his forehead and neatly split open the left eyeball. A gooey liquid leaked out with his blood, and a pale light reflected off the blade inside his mouth.

For the next few paragraphs, we get more than I’m willing to quote on the removal of said blade:

With his right hand he pulled on the hatchet, which made a horrible spurting sound as [it] finally came loose and blood sprayed out of Tatsumichi’s face.

He felt as if he were in a nightmare. Cracked in the middle, Tatsumichi’s head was now asymmetrical. It looked too unreal, like a plastic fake. Shuya realized for the first time in his life how malleable and fragile the human body [is].

Can Shuya’s feelings, his struggle not to vomit, hold any value after someone’s mutilated head has just been likened to cake? Daffy Duck, his bill spun to the back of his head by an exploding outhouse, would have to say no. And yet, the awkwardly translated gore-fest above is precisely why people read Battle Royale.

The current altar at which teens are sacrificed is a young adult novel called The Hunger Games. It’s the first in a trilogy by Suzanne Collins, currently in theaters, and not nearly as indebted to Battle Royale as many hardcore fans would argue. And argue they do, loudly, in bookstores, cinemas, comic shops, and on Facebook and Twitter. Coverage of their wrath is also ubiquitous, and we’ve heard Collins’ defense everywhere from ABC to the Christian Science Monitor:

I had never heard of that book or that author until my book was turned in. At that point, it was mentioned to me, and I asked my editor if I should read it. He said: “No, I don’t want that world in your head. Just continue what you’re doing.”

With a decade separating their works, Collins’ sophisticated use of today’s crucial issues makes Takami’s bloody statement seem downright cartoonish. Likewise, cries of plagiarism are absurd, in vain, and reek of the trolling that makes many internet message boards unbearable.

Collins’ protagonist in The Hunger Games is a teenage hunter/gatherer named Katniss Everdeen. Her world of Panem (formerly North America) has been ravaged by environmental catastrophes. Of particular significance is the rising of the the oceans, which fomented uprisings among a compressed, drought-stricken population. And because this was America, not India, the super-rich used military might to squash the rioting masses. Twelve Districts now comprise the leftover wasteland, where ninety-nine percent of the population has the pleasure of surviving on gruel and squirrel meat. They also find time to bake, sew and make soap while funneling natural resources to Panem’s ruling city, the Capitol (Katniss lives in District 12, formerly Appalachia, where they provide coal).

The Capitol, protectively situated west of the Rocky Mountains, is the home of attractive, well-fed people. They have highrise apartments with showers, clean, wide streets, and nothing to worry their sparkling little minds. They also force the dirt-poor Districts to participate in a reality-show spectacle for which the novel is named. Every year, a male and female teenager are chosen from each District and brought to the Capitol. There, as tributes, they feast on lavish meals in heart-attack proportions and receive tasteful make-overs to seem more palatable to television audiences. By this point, the teens and their handlers have conceived a story-line. They must present themselves as an engaging product for the psychological win.

Katniss, humble and admittedly a bit plain, has no idea how to sell herself. A brilliant hook rests, however, in the fact that her younger sister, Prim, was originally chosen for the Hunger Games. Chosen, that is, until our protagonist decides to volunteer, replacing her meek sibling. The live audience, and those watching from home, are astonished.

Celebrating the initiation of the 74th Hunger Games alongside Katniss is Peeta, the male tribute from District 12. They had only met once before, as children, when the boy gave her some burnt bread from his family’s bakery. Now they stand together, smiling till it hurts and high on mass approval. Soon they’ll face off in an extended manhunt where one may kill the other. Peeta, cooler than he appears during an interview, has no trouble dazzling Panem’s gimmick-hungry viewers:

…Caesar asks him if he has a girlfriend back home…

Peeta sighs. “Well, there is this one girl. I’ve had a crush on her every since I can remember…”

“She have another fellow?” asks Caesar.

“I don’t know, but a lot of boys like her,” says Peeta.

“So here’s what you do. You win, you go home. She can’t turn you down then, eh?” says Caesar encouragingly.

“I don’t think that’s going to work out. Winning… won’t help in my case,” says Peeta.

“Why ever not?” says Caesar, mystified.

Peeta blushes beet red and stammers out. “Because… because… she came here with me.”

The tech-couture world of clocks and rainbows that Katniss sees, where the chase of cheap titillation has atrophied attention spans to a nullity, is a marvelous critique on the United States. After all, a country gripped by successive manufactured wars needs, firstly, to be distracted. Secondly, they need the confidence boost that only court jesters can provide. Think of American Idol (including its advertisements, recaps and bevy of sister shows) as a carpet bombing of the mind. Having done its worst, we must now be sated by fluorescent rodeo clowns like Katy Perry and Nicki Minaj. Pop-stars by trade, they seem to have stepped right out of the Capitol.

But into her feverish concoction, Collins’ has stirred genuine soul. She doesn’t distance us with gore and absurdity, like Takami. Her story is told from an intimate first-person, and her heroine shines luminously throughout. In the scene below, Katniss hides alone in the gigantic wooded arena, one of six tributes still alive. Since Peeta revealed his crush, she’s forced herself to doubt his sincerity against mounting evidence in its favor. Then, Claudius Templesmith, voice of the Hunger Games, announces a controversial rule change, where:

…both tributes from the same district will be declared winners if they are the last two alive.

Claudius pauses, as if he knows we’re not getting it, and repeats the change again.

The news sinks in. Two tributes can win this year. If they’re from the same district. Both can live. Both of us can live.

Before I can stop myself, I call out Peeta’s name.

Takami’s story does have twists, turns and mysteries. But unraveling them memorably requires more finesse than he, or perhaps his translators, seem capable of. That’s no issue, however, in the extremely violent film adaptation. Battle Royale has never been released in the U.S. by a major movie distributor. Since 2000, only slick bootlegs have been available. Now, with The Hunger Games in theaters, Stars/Anchor Bay has released the unrated cult phenomenon on DVD and Blu Ray this March. For this (meaning the royalty checks to come), Takami should be eternally grateful. The downside is that he’s now entwined in something I’ll call “The Joss Whedon Factor.” Creator of the sensationally smart Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Whedon wasn’t invited to cosign for Twilight author Stephenie Meyer's home. Surprised? Don’t be. As far as riffing on established material goes, it isn’t what you write, but how.

And how often. Since Buffy, Whedon has rocketed through several other fan-favorite writing and directing projects. Stephenie Meyers, not so much. Similarly, Takami has about 42 inches of dust on his career. Never following up Battle Royale with anything other than his signature on film and manga contracts, he told ABC News, “I think every novel has something to offer. If readers find value in either book, that’s all an author can ask for.”

Undoubtedly. But the renewed attention on Battle Royale will likely vanish once Collins is swept aside by the next teen craze. Having captured the world’s eyes and ears again, Takami should do what so many of his students did.

Give us some fresh blood.

Justin Hickey was an editor at Open Letters Monthly, and writes regularly for Kirkus Reviews.