Mike Nichols: A Life, by Mark Harris

/Mike Nichols: A Life

By Mark Harris

Penguin Press, 2021

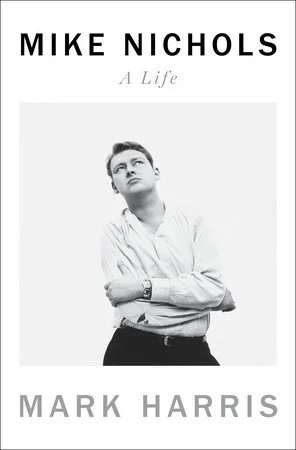

The photo on the cover of Mark Harris’ new biography of Mike Nichols shows the writer-director-producer-performer in his late 20s, arms wrapped around his body as if confined by an invisible straitjacket, his eyes peering upward, with an expression that could be petulance or pique. The photographer was Richard Avedon (of whom more later), iconic for capturing his subjects in dramatically theatrical poses and settings. (Think Nastassja Kinski erotically engaging with a giant boa constrictor.)

What Avedon captured in the 1960 portrait can perhaps be explained by the subject’s state of mind. Nichols had achieved rapid national fame as a performer—TV appearances, best-selling vinyl recordings, a healthy Broadway run—with his partner Elaine May. Emerging from Chicago’s improv theater movement, Nichols and May—their pairing as inevitably linked in mid-century entertainment as Tom and Jerry, Matrin and Lewis—took satiric shots at the era’s issues and foibles: teenage sex, adult adultery, the tyranny of telephone company operators (you had to be there), the curse of Oedipus brought to mid-century. With no props save for two stools and the occasional cigarette, the two became darlings of the hip, creating funny/sad vignettes that still tickle and sting.

But after several successful years, May was eager to move on—which she did, quite nicely, as a writer, director, and performer; she won a 2019 Tony as Best Actress at the age of 86. Nichols was left at sea, as he explained to Charlie Rose in a 1992 interview: “I didn’t know what I was [except] the leftover half of a comedy team.” Maybe in the Avedon portrait he’s looking for career guidance from the gods.

He received it not from Olympus, but from a veteran Broadway producer, Saint Subber, whose instincts suggested there was a director in Nichols waiting to emerge from the performer. Subber convinced him to helm a new comedy, Barefoot in the Park, Neil Simon’s take on a young frenzied married couple in New York City. Under Nichols’s expert eye it became an enormous, long-running success, and the gateway to his career. What he couldn’t have foreseen were more than five decades of creative triumphs (and a fair number of belly flops), countless awards, huge paychecks, and a reputation for versatility in so many media that only Laurence Olivier and Noël Coward could rival his impressive multitasking in the 20th century.

His beginnings were not auspicious. Arriving at the age of seven in New York from Berlin with his younger brother to join his immigrant Russian parents to escape Nazi oppression, he was the ultimate outsider: a Jew, knowing almost no English, and burdened by a medical condition that left him entirely hairless (his early wigs were cheap and required a noxious glue). He was also poor, his well-to-do doctor father having lost a small fortune before he died, leaving his embittered wife to support the family.

What Nichols did have was a keen intellect, verbal acuity, and a defensive, instinctive superiority. Writes Harris of Nichols’s brief college life at the University of Chicago: “Thrown off balance by everything around him, he responded by affecting a style of frosty, bored, hyper-cultured contempt for anyone or anything he found wanting in merit, serious intellect, and he expressed his scorn with such withering humor that his ability to destroy people with a sentence soon became the one thing classmates knew about him before they even met him.” It was a trait he never completely shed.

A flirtation with medical school went sour, and it was only by happenstance that he fell in with a Chicago improvisation group, whose seeds would later blossom into the highly influential Second City company. Already besotted by theater and film, he discovered a niche for his particular skills—and he found in Elaine May, a perfect partner in deliciously wicked satire—Burns and Allen crossbred with Masters and Johnson.

Barefoot won Nichols his first Tony Award (with nine more in his future). It was followed shortly after by the megahits, Murray Schisgal’s Luv and Simon’s The Odd Couple. (Other Simon collaborations, Plaza Suite, Prisoner of Second Avenue, and the film of Biloxi Blues cemented their professional relationship for years.)

It is a sad fact that Nichols’s magic touch onstage will be all but lost to history. His early triumphs were heralded as a rejection of the hoary Broadway comedies of the 50s that were often a series of laugh-milking gags, unmoored from character or situation. He brought comedy to a realistic, personal level, Harris writes, “rooting performances in psychological truth, and on everything he and May had discovered about getting laughs by refusing to chase them.” Nichols often told his comic actors, “Let’s do it as if we don’t know what’s going to happen. Play it as if it’s King Lear.”

Until 1970, when the Lincoln Center Library began video recording major theater events for professionals and students only, the specifics of these triumphs disappeared. Much was made of Nichols’s ability to create stage business that was intricate and side-splitting. Subsequent revivals of the Simon comedies have often proven the texts as pretty thin gruel, tired and dated without the Nichols touch.

Given his track record as a wizard stage director, it was not a surprise that Hollywood would send its siren’s call his way—and that his ears would be wide open. But few would guess, given his flair for comedy, that his tyro effort would be bringing to the screen the era’s most controversial and brutal play, Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Not to mention that his casting choices were the kind of audacious moves that would eventually become one of signatures. For George and Martha, he selected Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, the era’s greatest paparazzi magnets, celebrity adulterers, and supreme attention whores. Nichols knew next to nothing about the techniques of film directing, but was able to absorb like a thirsty sponge what he needed from the experts around him. The result was an unexpected masterwork, winning Taylor her second Oscar and Nichols his first nomination as director.

Closely following in 1967 was an even more significant film, The Graduate, an adaptation of an obscure novel and starring the most unlikely of movie stars, the New York theater-based Dustin Hoffman, physically unprepossessing and as far from the era’s notion of a leading man as could be imagined. (Robert Redford lobbied for the role). Nichols won the Oscar this time and watched with shock as the film became, says Harris, “not only an instant hit but a cultural milestone that was widely seen as Hollywood’s first great exploration of the generation gap”—and for a time the third highest-grossing film of all time.

The gods rarely smile for long on those blessed with early success (see Orson Welles for one). Their grins faded for Nichols’s next films: Carnal Knowledge was a success d’estime; the other three (Catch-22, Day of the Dolphin, The Fortune) were critical and financial disasters.

Enduring periods of creative malaise over the years (“. . . after one misstep too many, he would limp away, so hollowed out that he couldn’t imagine standing behind a camera again,” writes Harris), he nonetheless bounced back with films ranging from the political thriller Silkwood and the social satire Working Girl to the farcical, gay The Birdcage and the political satire Primary Colors, whose source was a satiric novel based on the clintons. But he never tackled a huge historical tapestry or a Spielbergesque extravaganza. (Nor, it could be argued did he ever achieve the true greatness or social relevance of The Graduate.) He preferred the intimate over the epic.

He seemed far more comfortable in the theater, where a tighter-knot roup of artists could form a surrogate family. Here too he leaned toward small canvases, taking on Beckett, Chekhov, Odets, Stoppard, Rabe, and Hellman, and musicals whose sources were the Gershwin canon and Monty Python sketches. But no Shakespeare, Moliere or Wilde. No Verdi or Mozart or Wagner.

Along the way he found time to marry four times (the final union, to Diane Sawyer lasted 26 years), raise three children, shepherd to stardom the careers of Gilda Radner and Whoopi Goldberg, struggle with a cocaine habit (including experiments with crack), survive a lifelong cigarette addiction, provide enough critical expertise to the megahit musical Annie to earn him a small fortune, and even reunite with Elaine May as George and Martha for a production of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? directed by Albee himself.

Age proved little impediment to his skills. Some of his best work was accomplished in his 70s: an HBO adaptation of Angels in America; staging the Monty Python Spamalot; and a stage revival of Death of a Salesman starring Philip Seymour Hoffman. More awards: an Emmy for Angels, two more Tonys for the others.

Despite vast amounts of money, he found himself occasionally badly in debt, thanks to an ongoing taste for expensive cars, multiple homes, rare paintings, and the decidedly louche hobby of buying, selling and breeding Arabian horses. Even his wigs became expensive, and his routine of affixing them to his skull became a lengthy routine: “It takes me three hours to become Mike Nichols,” he told a friend.

He could be profligate on set as well, insisting for one scene Regarding Henry that the caviar the actors were consuming onscreen wasn’t of the appropriate quality. “It’s disgusting,” declared Nichols. He reshot, to great expense, the scene with a fresh supply of Beluga—and snapped up the leftovers to take home.

Much of his elevated taste could be attributed to Richard Avedon, who, in 1960, the time of the book’s cover portrait, took him “as a project and a pupil.” The photographer had a wide and deep familiarity with the wealthy and accomplished, and he became in Nichols’ words, “the perfect cicerone.” On an extended vacation in Jamaica, Avedon and his wife gave their pupil “a crash course in two subjects that preoccupied and fascinated him: how to be rich and how to be a celebrity.” He did both with joy and panache throughout the rest of his life.

Perhaps it’s an appropriate time to address a topic that has become a point of controversy. In the 2017 oral biography of Richard Avedon, the author, Norma Stevens, a 30-year professional associate and friend of the photographer, disclosed that he and Nichols were lovers for more than a decade, quoting Avedon as saying “[we were] made for each other ” and even that they “considered eloping.” Harris addresses the point in a lengthy footnote, discounting Stevens’ account by asserting he could find no corroboration among those he interviewed. Some LGBTQ activists have objected to what they consider a predictable whitewash, particularly egregious coming from a Harris, a gay man, writing with “the approval” of Diane Sawyer and the three Nichols offspring, all of whom declined to be interviewed. So, bromance or romance—or more precisely, what was up with Nichols’ sexual identity, and does it matter? I’m among those who think it does.

In all other matters, however, Harris is an ideal biographer. (His dazzling 2008 Pictures at a Revolution is one of the best pop culture books I’ve read.) He’s expert at the inner workings of both theater and film, and his accounts of all of the major works offer a perfect balance of technical matters and insider tidbits, gleaned from an impressive roster of interviews. (Harris began his major research in 2015, a year after Nichols died, but had discussed The Graduate with him for the 2008 book.)

Harris is clearly a fan, but not blind to his flaws. Nichols could be “sadistic” to actors in rehearsal, and quite capable of cold-heartedly firing them midstream if they were found wanting. Yet in the book there are enough encomia dedicated to Nichols’s human and artistic virtues to prompt its own volume, many resembling this from Jake Gyllenhaal: “Mike was . . . a Jedi master of intellectual seduction, someone who could bring you into his orbit in ways that verged on sorcery.” (He was also a brilliant raconteur. Those who seek out his many live interviews and the Nichols and May routines on YouTube will be generously rewarded.) For the most part, actors adored him, especially when he guided them to winning awards. “He’s my master and commander! My king!” exulted Meryl Streep on accepting her Emmy for Angels in America.

Harris is skillful at evaluating and interpreting the critical consensus on the director’s midcareer oeuvre. In 1991, the Harrison Ford flick Regarding Henry was greeted with reviews that were less than kind. (“An unimaginably bad movie from none other than Mike Nichols, who appears to have lost his mind,” spat David Denby in New York magazine). From Harris:

The collective reaction imparted jolting news to Nichols about exactly who they thought he was—a cynic and a pessimist who disdained warmth and sentiment. . . . There was a Nichols they liked and a Nichols they hated. The Nichols they liked was the acid anatomist of human behavior whose movies were extensions of his barbed, unsparing routines with Elaine May in which vanities and pretensions were laid bare almost prosecutorially. The Nichols they hated was a valorizer of the celebrated and well-to-do, a man who had become completely attached to what Rolling Stone dismissed as “haute bourgeois marital dramedy . . .”

And Nichols was perfectly capable of hating himself. “Self-loathing” comes up as a descriptor more than once. And there’s this to his therapist: “I gotta tell you, I really am tired of being Mike Nichols. Get me out.”

The book is long, but I would happily have had more of it. In many ways it’s a party with a fabulous guest list: George C. Scott, Walter Matthau, Truman Capote, Stephen Sondheim, Julia Roberts, Al Pacino Tony Kushner, Nora Ephron, Anne Bancroft, Paul Simon, Lillian Hellman, Emma Thompson, Leonard Bernstein, Lorne Michaels are there, as are brief drop-ins by Jackie Kennedy, Orson Welles, Susan Sontag, John Travolta, William Styron, Arthur Miller, Marilyn Monroe, and almost every other cultural luminary of the era

But the most welcome appearances are those of Elaine May—collaborator, co-star, critic, foil, soulmate, friend-to-the end, who steals every scene she’s in. I don’t think Nichols would have minded my ending with this appraisal from Her Royal Slyness at the Kennedy Center Honors: “Mike has chosen to do things that are really meaningful, and have real impact and real relevance, but he makes them so entertaining and exciting that they’re as much fun as if they were trash.”

He has his important biography. Now it’s her turn.

—Michael Adams is a writer and editor living in New York City. He holds a PhD from Northwestern University in Performance Studies.