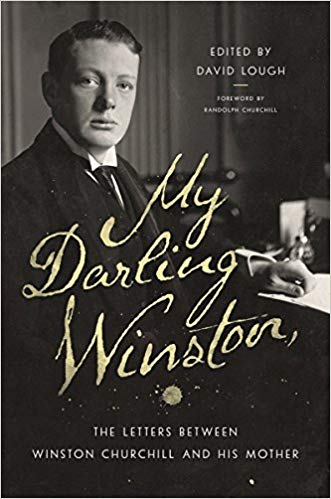

My Darling Winston: The Letters Between Winston Churchill and His Mother

/My Darling Winston: The Letters Between Winston Churchill and His Mother

Pegasus Books, 2018

This handsome new volume from Pegasus Books, My Darling Winston, collects forty years of correspondence between young Winston Churchill and his mother, the celebrated American heiress Jennie Jerome, who married Lord Randolph Churchill, the second son of the Duke of Marlborough, in 1874. The correspondence begins when Winston is six years old and extends to his mother’s death in 1921, and according to editor David Lough (author of 2015’s fascinating No More Champagne: Churchill and His Money), this volume represents the largest, most comprehensive collection of these letters ever assembled.

Lough himself is omnipresent throughout the book, thank God. He’s a perfect concierge, gliding soundlessly to your elbow before every new batch of letters and tactfully whispering just enough information to keep you from floundering in the blizzard of proper names and darting allusions to the news of the day. There are quick, discreet footnotes on every page, and the book is also generously supplied with gorgeous black-and-white photos that follow our correspondents from year to year. There’s also an invaluable appendix identifying the players that warrants a separate bookmark of its own.

My Darling Winston provides a strange and almost pleasurably irritating reading experience. On the one hand, there’s the beguiling spectacle of two very intelligent people steadily learning how to communicate with each other through the wonderful, bygone method of handwritten letters; it’s not just that the Winston and Jennie are constantly learning how better to use the medium, it’s also that they themselves are shaped by that medium over the years.

But they’re both such awful people, which is depressing enough in the case of someone as vivacious and charismatic as Jennie Jerome (perfectly captured in Stephanie Barron’s upcoming novel That Churchill Woman), but it veers into outright Rosemary’s Baby territory when it extends to include Winston-Churchill-as-toddler being every bit as oafish and narcissistic in short pants as he would be 50 years later in Downing Street. When you read the letters between these two, you see them constantly angling around each other, constantly pushing each other, and, inevitably, constantly disappointing each other.

It starts early, with little Winston forever hounding his “Darling Mummy” for money, telling her “I am absolutely ‘oofless’” and then waiting with a pointed combination of arrogance and impatience for the money to appear. When he’s a bit older and a bit more self-confident, he’s even worse, tasking his (by then) long-suffering mother with not being a sufficiently vocal Winston-booster. “Never was there such modesty as yours for me,” he writes in some variation over and over, even while she’s mentioning his name at every bright-society ball and singing his praises to the King when she could have spent a more pleasant evening talking to His Highness about racing horses instead of her boringly hangdog son.

He has a round, baby face; he glorifies himself endlessly; he sponges up and regurgitates all the latest gin-club slang; he’s always short of funds but floats through life with the blitheness of the manner born. Every time he starts a letter with “my dearest Mummy,” you imagine yourself trapped in a version of Brideshead Revisited told by Boy Mulcaster.

More sad than amusing is the fact that in the overwhelming majority of instances, he’s as bad a son to his mother as she’s a mother to her son. By the end of the volume, it’s impossible to deny that a certain species of love has grown and entwined between these two, but it’s likewise impossible to avoid the awareness that they’re each slaves to a second and very loud kind of love, love of the limelight, love of hearing their names on the lips of other people. As any student of fame will know, that second kind of love preys first and most perniciously on the first kind, and this is the riveting psychic drama that plays out underneath the surface of My Darling Winston. That makes it a valuable addition to the near-endless Winston Churchill library but a surprisingly dark one.

Steve Donoghue was a founding editor of Open Letters Monthly. His book criticism has appeared in the Boston Globe, the Wall Street Journal, The Spectator, and the American Conservative. He writes regularly for the National, the Washington Post, the Vineyard Gazette, and the Christian Science Monitor. His website is http://www.stevedonoghue.com.