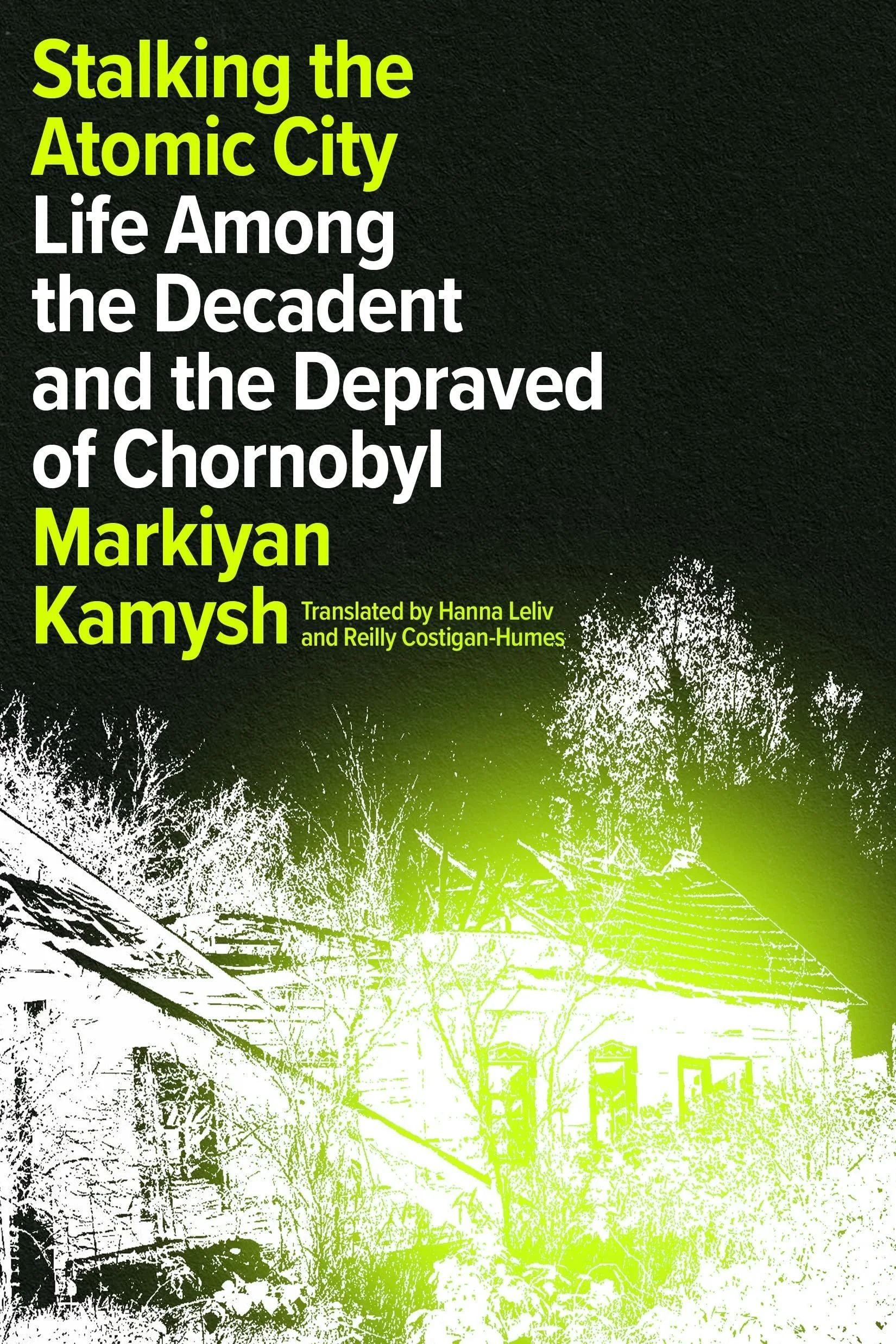

Stalking the Atomic City by Markiyan Kamysh

/Stalking the Atomic City: Life Among the Decadent and Depraved of Chornobyl

By Markiyan Kamysh

Translated by Hanna Leliv and Reilly Costigan-Humes

Astra House, 2022

It’s only been with comparatively recent news cycles in the last month that a great many people have been reminded that the city of Prypiat and the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, the sites of the calamitous 1986 nuclear disaster (so memorably dramatized in the great 2019 miniseries) are located in Ukraine. The reminder was horrifying; it came when stories broke of fire-fights happening between Russian invaders and Ukrainian defenders on the grounds of the abandoned power plant, prompting everybody to wonder suddenly if Chernobyl could still be dangerous.

The underlying truth is that Chernobyl is still dangerous, weapons-fire or no weapons-fire. The shattered number 4 reactor has been encased in gigantic steel and concrete containment building (an unsound encasement, resting on cracked foundations), but all the vast surrounding area making up the “Exclusion Zone,” all the soil, all the trees, all the running waters, all of it is still suffused in radiation. Short visits conducted by state-certified guides are popular, but you’ll be cooking your insides the whole time you’re there.

Which makes the very premise of Ukrainian writer Markiyan Kamysh’s book all the more stark-staring remarkable. “Stalking the Atomic City,” originally published back in 2015 and here translated into English by Hanna Leliv and Reilly Costigan-Humes, details in catchy and often evocative language Kamysh’s many clandestine visits to the Exclusion Zone. For years, he regularly eluded the guards and wardens in order to tramp through the wilderness, walk the empty roads, and especially camp out in the abandoned buildings.

It isn’t just the official guardians of the Exclusion Zone he needs to avoid: there are also various dangerous sketchy characters who likewise go where they shouldn’t. But even so, he manages to find comrades in this daftest of all adventures, and amidst the rivers of cheap alcohol, the parade of filthy sleeping bags, and the absolutely endless amount of smoking (one way or another, Kamysh seems dead-set on not making old bones), there are surprisingly frequent moments of happy memories:

During trips like that there are many warm, pleasant nights when all of us gather around a fire and talk for a long, long time until everyone calls asleep. Until we burn our sneakers because we’ve come too close to the fire. We chug liquor diluted by swamp broth, look at the stars, and stare at the fire, and it seems as if there’s nothing more beautiful out there than the Zone.

This isn’t true, of course – in fact, it’s damn near delusional, and delusional in a pointedly nihilistic 21st century manner. There’s nothing beautiful about an irradiated ghost town that’s attacking the cells of your body every minute (diluting drinks with “swamp broth,” God help us). And yet, Kamysh keeps going back there, seeking something he can hardly name:

Once you have traveled the lengths and breadths of Chornobyl Land, once the Prypyat skyline has turned into a mundane sight, an unremarkable backdrop for a late-night tea party, once you have climbed the Chornobyl-2 antennas so many times that you have lost track, once all the abandoned collective farms, villages, hamlets, and forestry towers have long been explored – then you start searching for things unattainable.

There’s a forensic reading that makes all this look like exactly the necrotic grandstanding it certainly was. Bookstores are full of titles extolling the virtues of camping out in the wild, and that makes such titles toxic for a certain rabid strand of anomie-drenched social media orphans, hence the evident need in “Stalking the Atomic City” to go further, to corrupt the source, to extoll the virtues of camping … in a nuclear wasteland.

And if there’s a higher, non-forensic reading, some nonsense about finding salvation even at the extremities of tragedy, here’s hoping readers don’t take it seriously enough to think about booking a trip.

Steve Donoghue is a founding editor of Open Letters Monthly. His book criticism has appeared in The Washington Post, The American Conservative, The Spectator, The Wall Street Journal, The National, and the Daily Star. He writes regularly for The Boston Globe, the Vineyard Gazette, and the Christian Science Monitor. He’s a books columnist for the Bedford Times Press and the Books editor of Big Canoe News in Georgia, and his website is http://www.stevedonoghue.com.