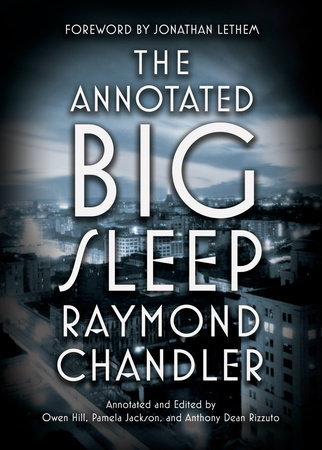

The Annotated Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler

/The Annotated Big Sleep

by Raymond Chandler

Annotated & Edited by Owen Hill, Pamela Jackson, and Anthony Dean Rizzuto

Vintage Crime, 2018

The Black Lizard label of Vintage Crime has produced one of the summer's least likely and most fascinating volumes: a thoroughly, exhaustively annotated edition of Raymond Chandler's 1939 novel The Big Sleep, which was a favorite of hundreds of thousands of readers and then became a favorite of millions when Howard Hawks adapted it in 1946 in a movie starring Lauren Bacall and Humphrey Bogart. The novel is a muscular, slightly oily sock to the jaw – it seems about as hospitable to a scholarly annotated edition as a single tweet from Kanye West.

It seems, in other words, like precisely the kind of thing Chandler himself would have crafted a quip to deride. It therefore takes a measure of courage to pitch in on such an annotated edition, and it's greatly to the credit of editors Owen Hill, Pamela Jackson, and Anthony Dean Rizzuto that they've produced something as unfailingly interesting as this The Annotated Big Sleep. Some annotated editions feel startlingly relevant specifically because scarcely any reader would have thought it was necessary; this book is a perfect example of that.

One of the secrets is to Go Big, and our editors do that right from the start:

The Big Sleep does more than even Chandler intended it to do. Partly by design and partly by happy contingency, the novel dramatizes a cluster of profound subjects and themes, including human mortality; ethical inquiry; the sordid history of Los Angeles in the early twentieth century; the politics of class, gender, ethnicity, and sexuality; the explosion of Americanisms, colloquialisms, slang, and genre jargon; and a knowing playfulness with the mystery formula – all set against a backdrop of a post-Prohibition, Depression-era America teetering on the edge of World War II.

Luckily for everybody involved, the editors then immediately add: “For all this, The Big Sleep reads easy. And it's a ripping good story.”

There follows 450 pages of expounding, explicating, and, since Chandler was a tough guy, often a lout, and thoroughly a product of his time and place, not-infrequent low-heat excoriating. There's a coarseness running under the polished circumstance of The Big Sleep that's born in large part of the playfulness mentioned in the Introduction. Such playfulness can get a hat-tip in general context, but since the 21st century is an almost entirely humorless era, it must always get a dutiful knuckle-rapping in the specific. Take a famously funny scene early in the novel:

“Back again,” I [the intensely heterosexual Philip Marlowe, of course] chirped airily, and waved a cigarette. “Mr. Geiger in today?”

“I'm – I'm afraid not. No – I'm afraid not. Let me see – you wanted …?”

I took my dark glasses off and tapped them delicately on the inside of my left wrist. If you can weigh a hundred and ninety pounds and look like a fairy, I was doing my best.

The editors can't pounce on such vulgarism fast enough:

The implication being that big men are big men, evidently – masculine and heterosexual. “Fairy” for a man thought to be homosexual or perceived to be effeminate is an Americanism that seems to have entered the language in the late nineteenth century among the gay underground: the transgender author Jennie June, born as Earl Lind, thought it derived as an expression of gratitude among sailors deprived of female companionship on long voyages. When a young sailor offered to take the place of the absent woman, he would be “looked upon as a fairy gift or godsend” and referred to as “the fairy.”

This is the first of five slang terms for “gay” that Chandler uses, as if chasing the concept hysterically around the lexicon. Or perhaps as if trying to outdo Hammett, who used only three such terms in The Maltese Falcon.

People who annotate trifles like The Big Sleep run an unavoidable risk of coming across as Gertrude Stein's “village explainers,” (the only sure safeguard is to annotate with tongue firmly in cheek, but alas, see above) and readers will run afoul of such needless pedantry from time to time in this volume. Chapter Thirteen of the novel, for example, begins: “He was a gray man, all gray, except for his polished black shoes and two scarlet diamonds in his gray satin tie that looked like the diamonds on roulette layouts.” For which there's a note “Note the repetition of the word “gray” in the description of Mars ...” Well yes.

But it's mercifully controlled. Ironically, one of the most encouraging things about The Annotated Big Sleep is the amount of blank-page space that's free of annotations. It's a sure sign of the editors' understanding that these blank spaces tend to increase in size and frequency as the novel picks up speed; it's a good host who knows to get out of the way once the party gets going, regardless of how crucial they were to getting it started. As with Dracula or Little Women or Pride and Prejudice – all of which have been the subject of thoroughly excellent annotated editions in recent years – The Big Sleep is perfectly capable of grabbing and holding readers without the aid of literary chaperones. So – again, perhaps ironically – it's the novel's most devoted fans who will love this edition the most.

Steve Donoghue was a founding editor of Open Letters Monthly. His book criticism has appeared in the Boston Globe, the Wall Street Journal, and the American Conservative. He writes regularly for the National, the Washington Post, the Vineyard Gazette, and the Christian Science Monitor. His website ishttp://www.stevedonoghue.com