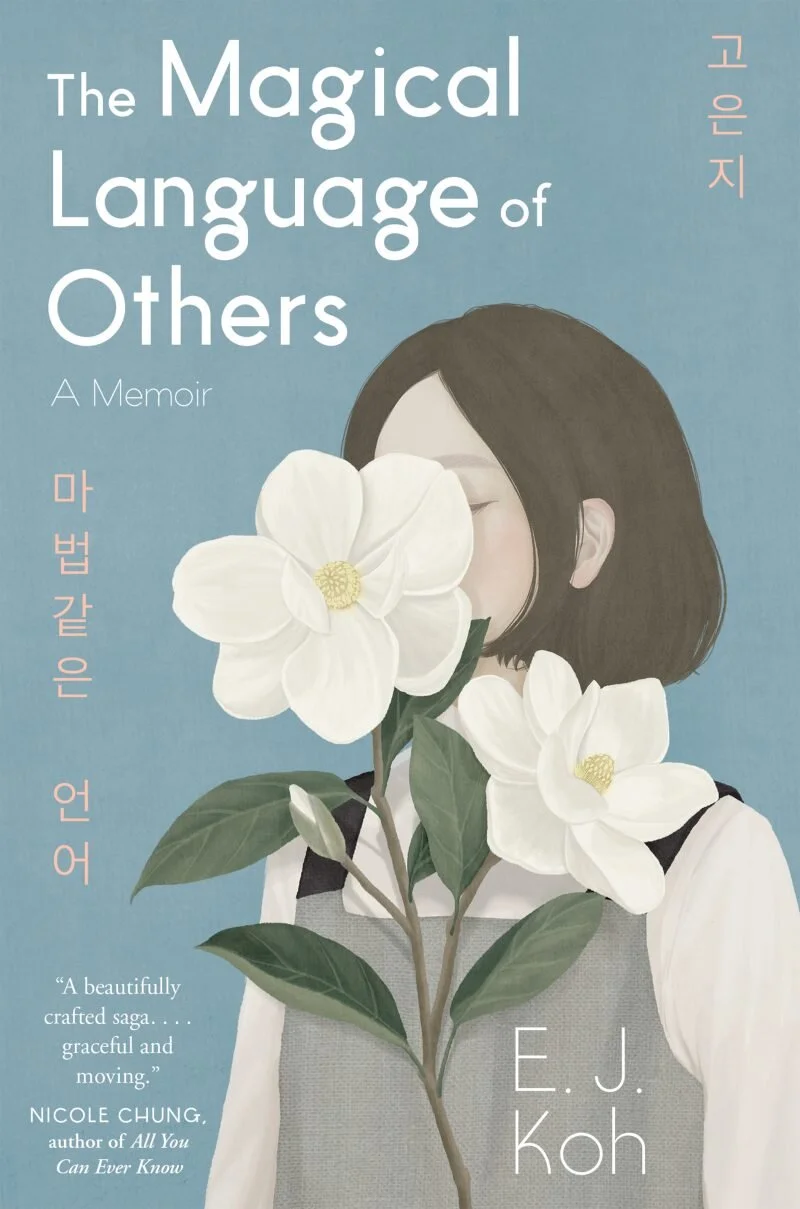

The Magical Language of Others by E. J. Koh

/The Magical Language of Others

by E.J. Koh

Tin House Books, 2020

Nearly every teen girl has probably had their own Home Alone fantasy at least once. As one’s age ticks upward, so does the restlessness for independence, particularly from one’s mother. She’s embarrassing. She’s restrictive. She seems out to make you unhappy. But like Kevin McCallister’s startling realization, it’s only when that figure is truly absent that a child begins to understand the power of a parent’s presence.

E.J. Koh didn’t have much say in the matter when her parents, residents of the United States for a decade, announced they were repatriating to South Korea for a too-good-to-pass-up job opportunity. Sure, our author could have gone with them, but with a life fairly well established in California by age 14, it wasn’t exactly a consideration that stayed too long in her mind. Nor did it seem to be a mandate from her parents, who arranged for her to live with her older brother until she was ready to go off to college.

In 2005, her parents had been gone nineteen months when she began receiving handwritten letters from her mother, all in Korean except for a few English words peppered in. These letters supplemented other communication Koh had with her mother, but seem to have added something different. Translated by the author and collected in her new memoir, The Magical Language of Others, they read like an extended, fussing hand, hoping to hold onto that mother-daughter bond across an ocean of distance. Though we find out immediately that the author never wrote her mother back, we know the letters held immense meaning:

Once a week, a letter came. I heard her voice, closer than it felt over the phone. I read them in my room, sitting at the desk, standing in the doorway, lying on the bed. I folded the letter and slipped it into its envelope. I placed it on my nightstand. I kept her close. I read a letter once or twice. Moving my lips, I read it again. Each time, I hoped to see something new, a word that I had missed. When I put it away, a panic returned. I took out the same letter and, with no thought to what I had read before, started over.

There is no dissection of the letters or of the author’s feelings about the absence of her mother in those critical years of development into womanhood. Indeed, the letters are presented mainly without comment and in between the author’s recollections of those years of physical estrangement. She is not forthright with her feelings, but the selected memories hint at her emotions: an intensive language course in Japan at age seventeen unveils a need for belonging as she bonds with her fellow students; a story of her family background leads to a questioning of identity; finally, her dive into the world of poetry hints at her lingering resentment and feelings of abandonment.

There is a whole shadow self lingering behind the words of this book; it only suggests the true pain and longing that the reader can feel in the pit of their stomach. There is no doubt that a second book’s pages could be filled with all that’s left unsaid here. The absence of such words gives this book a quiet, melancholic tone. Wounds kept hidden in this book do not interrupt its smooth, elegant prose, though it is the literary equivalent of sweeping matters under the rug.

The void left by the absence of such a discussion leads to the consideration of what the mother-daughter pair may have missed out on during those years. As a teenager, a girl may push her mother away, but relies upon her like an anchor, leaving a trail of guide rope as the girl pushes herself further and further outward into the world. The learning of herself comes in the distancing, while knowing she can always come home. For our author, home could not be her mother because her mother was not at home.

Meanwhile, Koh mentions in her introductory passage (which doubles as her translator’s note) that her mother, at times in her letters, dips into the third-person perspective, referring to herself as “Mommy.” As the author notices, “Mommy addresses a child, who remains one in her letters.” She suspects that these moments were her mother’s act of parenting. Perhaps the guilt of leaving behind her children and the loss of the maternal role compelled her mother to put to paper these thoughts and pieces of advice as an attempt to reclaim an identity lost with the move.

The harsh reality that the book exposes is that what is gone is truly gone; as is true in family connections and in sleep, there is no making up for what was lost. The mother-daughter clash that the majority of pairs experience, especially in the teenage years, may be brutal, but it hardens the bond between them and cements their love. As both the author and her mother recognize, she largely raised herself in those years and though she did so admirably, the feelings of floating adrift remains with her as an adult. The loss, like the letters, lingers.

The Magical Language of Others is a beautiful, sorrowful kind of wandering into the past. It is the kind of recollection that has spikes, the ones that, despite the passing years, still tear at us when we pull them out of the proverbial, or even literal, closet.

—Olive Fellows is a young professional and Booktuber (at http://youtube.com/c/abookolive) living in Pittsburgh.