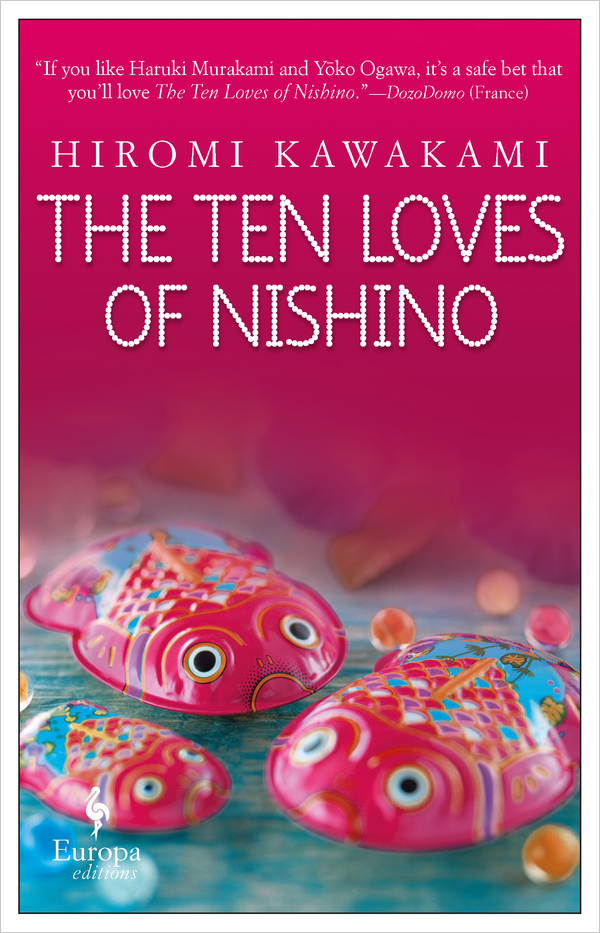

The Ten Loves of Nishino By Hiromi Kawakami

/The Ten Loves of Nishino

By Hiromi Kawakami

Translated from the Japanese by Allison Markin Powell

Europa Editions, 2019

The Ten Loves of Nishino, Europa Editions’ newest English-language translation of a novel by Hiromi Kawakami, the author of the very popular The Nakano Thrift Shop, comes to its American readers nearly two decades late; Nishino Yukihiko no Koi to Boken appeared in Japan in 2003, and here it gets its first translation into English by Allison Markin Powell.

The book’s title in English refers to the serial dating habits of a man named Yukihiko Nishino, and the specific number (not present in the original Japanese title) is something of a rough estimate: in truth, virtually all of the women in the book’s ten standalone chapters are in some way or other “loves” of Nishino. They’re all enamored of this man, and he himself is possibly, briefly, at least theoretically enamored of all of them. The ten stories are connected almost exclusively by Nishino’s presence in each; they women don’t know each other, and they meet Nishino at different points in his life - although his odd magnetism (and disturbing propensity to be accompanied by dragonflies and other insects) never seems to change. Each story presents readers with a quick glimpse of the lives of the women involved before linking those lives to Nishino; after a couple of stories, you find yourself waiting to see how he’ll make his appearance.

“If I had a hundred million yen,” Nishino muses at one point, “I would spend it on making the girls I know happy.” But if these stories make one thing clear, and there is, ultimately, precious little they make clear, it’s that these women in Nishino’s lives require a great deal less than a hundred million yen to make them happy. In fact, after a while, readers will suspect the author of making a running sarcastic commentary on just how low a bar modern men have to clear in order to become objects of fascination. As businesslike Mrs. Sasaki puts it in the story “Marimo”:

For one thing, Nishino was quite a handsome man. Secondly, he was clean-cut. Furthermore, Nishino was kind and courteous. And to top it all off, he had a steady job with a respectable company.

Yes, you want to add, but he obviously doesn’t care about you. Any of you. And although quite a few of the women profess to love Nishino in some way or other, they don’t seem to care about him either. In the book’s strongest story, “The Kingdom at Summer’s End,” for instance, forthright Reiko knows exactly what she wants, and it isn’t quite deep, meaningful companionship:

I’d really like to have sex with him ... I want him to wrap his arms around the nape of my neck ... I’d like to tear a fresh-baked loaf of bread in half and devour it with him ... I’d like to take his fingers in my mouth ...

This procession of erotically charged encounters is fascinating to read, but it admits of no change, no development. Nishino never shares anything of his inner self with any of the women he encounters, and readers following along through each of those encounters will quickly begin to suspect this is because he has no inner self to share. This would be interesting on a plotting level if all the women he meets were shallow and undiscriminating, but not all of them are: some, we get the strong impression, would see through this romantic grifter in two seconds, and indeed, some do - but it doesn’t stop them from breaking bread with him. If the book is intended as a commentary on the bleak nature of modern romance culture, it’s as insightful as it is depressing.

Powell is an experienced translator from the Japanese, so we can assume that the flat, affectless artlessness on every page of the book is the author’s decision rather than the translator’s failure, an assumption bolstered by the curiously monochrome tone of so much translated contemporary Japanese literature, regardless of who’s doing the translating. Whatever its origin, the drab prose throws extra emphasis on the plot, and as one of Nishino’s women mentions, “The trouble with wanting all of a boy like Nishino was that it was predictable.”

--Steve Donoghue is a founding editor of Open Letters Monthly. His book criticism has appeared in The Boston Globe, The Wall Street Journal, The Historical Novel Society, and The American Conservative. He writes regularly for The National, The Washington Post, The Vineyard Gazette, and The Christian Science Monitor. His website is http://www.stevedonoghue.com.