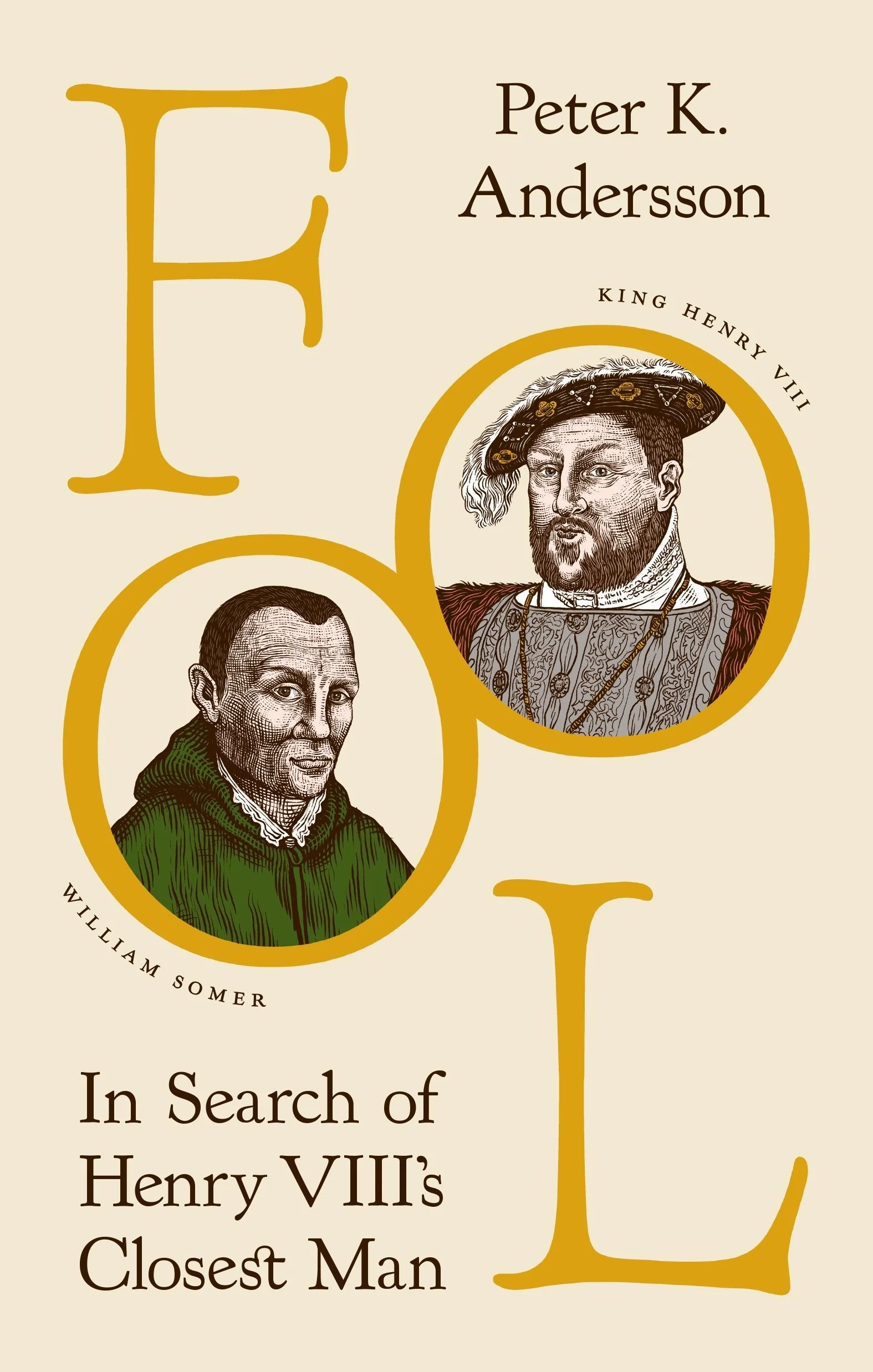

Fool by Peter Andersson

/Fool: In Search of Henry VIII’s Closest Man

By Peter K. Andersson

Princeton University Press 2023

When encountering Peter Andersson’s new book Fool, readers are immediately both encouraged and mortified, in quick succession. It’s a swoony little one-two experience. Readers are told that Andersson is senior lecturer in history at Orebro University in Sweden, but virtually at the same time, they also see the book’s two epigraphs. One is from Charlotte Higgins: “The stories we choose not to tell about the Tudors are as revealing as those we do.” The other is from Neil Sedaka’s song “Oh! Carol”: “I am but a fool.” One bit of credibility, two bits of idiocy. Hardly reassuring.

Thankfully, the book leans more toward credibility. Not enough credibility to extend to including an actual bibliography even for a work of barely 200 pages, mind you — let’s not be unrealistic (if you’re curious enough, you can always crawl through his Notes with pen and paper, constructing the bibliography yourself, since academic publishers can’t be bothered to do that anymore). But certainly the credibility that arises naturally from Andersson’s perceptive and often subtle handling of his sources. He’s read through every historical mention of his subject, Will Somer, the court fool to England’s King Henry VIII.

All those historical mentions don’t amount to much — certainly not to anything like the portrait of a man. To compensate (one must not say “pad”), Andersson examines what it meant to be a court fool in Tudor England. He breaks down this odd employment into two distinctions: the Fool as an acidic commentator given a latitude of address that would have sent the King’s other intimates to the Tower, and the Fool as an imbecilic object of scorn given the same latitude. In both cases, Henry’s fool could make wry quips about, say, Anne Boleyn’s physical appearance that would have cost anyone else their life. But in the former case, the fool is in on the joke, whereas in the latter, he’s just burbling impulsive thoughts without malice — and with no bigger motive than getting a pat on the head, or some table scraps. Either the fool is a canny comedian or a pratfalling house pet, like a basset hound with a penchant for malpropisms.

Andersson readily admits that we don’t know enough about Somer even to know which he was, although of course Andersson would rather be writing a book about a sly comedian than a mentally retarded innocent. “It cannot be said that Somer was considered a clever wit, but neither is there proof enough to cast him in the role of a disabled natural fool,” he writes. “His distinguishing characteristic is an inclination to make gaffes, to speak too quickly, the tongue that runs away while the wit comes halting after” — which of course could certainly be said of what Andersson calls a natural disabled fool.

His work in these pages showing how other contemporaries saw Somer is fascinating and surprisingly interesting, a kind of detailed addendum to more sweeping works like Beatrice Otto’s Fools Are Everywhere. Andersson’s thoughts about these two kinds of fools are consistently thought-provoking, but is there enough meat on the bone here for readers to forget Neil Sedaka? Water-treading passages like this make that unlikely:

The fool stands as a symbol of something fundamental to history — the simple individual in the midst of great events, an unavoidable victim, vainly trying to show the panjandrums the ordinary people at the receiving end of their choices. And to walk among them as a mirror showing them that they are the same, if only one of them had stopped to look. Thither he lingers awhile, irrespective of whether he is regarded, before quietly lumbering out of the lamplight to sleep with the spaniels.

180 pages is probably too few to allow this kind of pap without giving readers the impression that this book should more properly have been whittled into an appendix to a new Henry VIII biography rather than pumped up into a stand-alone title of its own. But readers who’ve encountered Will Somer and his like in other histories (or some high-profile Tudor historical fiction) will enjoy learning what little more about him is out there to know.

Steve Donoghue is a founding editor of Open Letters Monthly. His book criticism has appeared in The Washington Post, The American Conservative, The Spectator, The Wall Street Journal, The National, and the Daily Star. He has written regularly for The Boston Globe, the Vineyard Gazette, and the Christian Science Monitor and is the Books editor of Georgia’s Big Canoe News

Steve Donoghue is a founding editor of Open Letters Monthly. His book criticism has appeared in The Washington Post, The American Conservative, The Spectator, The Wall Street Journal, The National, and the Daily Star. He writes regularly for The Boston Globe, the Vineyard Gazette, and the Christian Science Monitor and is the Books editor of Georgia’s Big Canoe News.