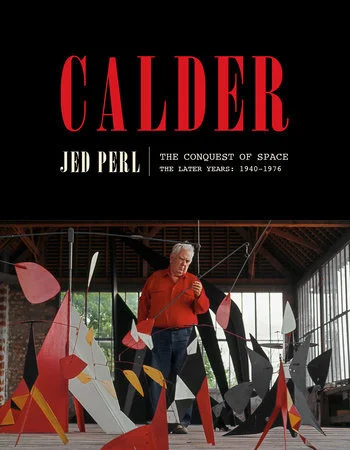

Calder: The Conquest of Space - The Later Years by Jed Perl

/Calder: The Conquest of Space - The Later Years: 1940-1976

By Jed Perl

Knopf, 2020

Jed Perl’s monumental two-volume biography of sculptor and artist Alexander Calder concludes here with The Conquest of Space - The Later Years: 1940-1976, covering decades that saw “Sandy” Calder go from a modernist firebrand to a white-haired elder statesman of the American art world. Perl, a brilliant art critic, succeeded in getting the Calder Foundation’s stamp of approval for an official biography aimed at securing Calder’s place at the forefront of the American avant-garde art ranks, and that approval gave Perl access to a vast treasury of Calderiana that especially helped to flesh out the man’s early years.

This second volume takes advantage of the same kind of open access to records, bringing readers particularly into the relaxed and surprisingly welcoming private life Calder and his wife Louisa shared for decades with friends and family members in homes like the one they had in Roxbury, Connecticut. Perl has combed through every scrap of documentation connected with Calder (this second volume has over 40 pages of often discursive notes), and he time and again combines the best elements to produce wonderful set-details:

Like many people, Edna Warner was struck by how wonderful the Roxbury house smelled, the atmosphere saturated with strong scents of freshly baked bread, garlic, cheese, and wine - a European bouquet of flavors then still relatively unfamiliar in the United States. To Warner, Calder himself wrote a couple of days after Christmas 1945 of the guests they’d been having. “We had a very pleasant time over Xmas with 2 Spaniards, 1 Greek, 2 French, 1 Turkey, + innumerable bottle + other gifts in the house - and all a bit overcome by gifts, wrapping paper, string, ribbon and the liquid diet and would drop in our tracks + snooze in whatever space we could arrange.”

All these details assemble to make these two volumes of Perl’s Calder the definitive biography of its subject, but the subject itself presents often insuperable problems even for a biographer as relentlessly upbeat and even occasionally starry-eyed as Perl. These problems are twofold: first, since these Knopf volumes are well illustrated, readers are presented with the same challenge that has always faced students of the avant-garde, presented with a manifestly ugly creation - book, symphony, painting, building, or, in Calder’s case, “mobiles” and various heaps of scrap metal - and told either that it isn’t, in fact, ugly, or that its ugliness is a strength rather than a defect. Perl has been writing about modern art for a long time (his New Art City is rightly considered a classic); he’s long since learned all the ways that exist to talk away this first problem.

The second problem is more fundamental to the art of biography, which is that “Sandy” Calder was very, very often a brusque, oblivious boor. This is obviously not an observation that would please the Calder Foundation, and Calder never makes it - but avoiding it requires frequent displays of rhetorical ambidexterity. About the Calders, Perl tells his readers that “it was difficult to dislike them if you were actually acquainted,” and certainly Louisa seemed always to humanize “Sandy” in almost all circumstances. But the man himself? He was “an imperturbable optimist,” Perl claims, but if this is true, it was an optimism often maintained at the expense of others. When a fire swept through the Roxbury house, for instance, Calder in his Autobiography mocked the firefighters who risked their lives to save the building. Perl can’t quite apologize for his hero, so:

If Calder’s comic touch never left him, there were times when it wasn’t in the most perfect taste. His bearish charm could leave people unaware of his deeply critical comic intelligence - of the bit and even the knife cut that were so often disguised by his smiles, mumbled words, and sleepy hazel eyes.

Readers of The Conquest of Space won’t have any trouble spotting the knives. The bearish charm is often more elusive, but maybe that’s the nature of this particular beast.

—Steve Donoghue is a founding editor of Open Letters Monthly. His book criticism has appeared in The Boston Globe, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, and The American Conservative. He writes regularly for The National, The Vineyard Gazette, and The Christian Science Monitor. His website is http://www.stevedonoghue.com.