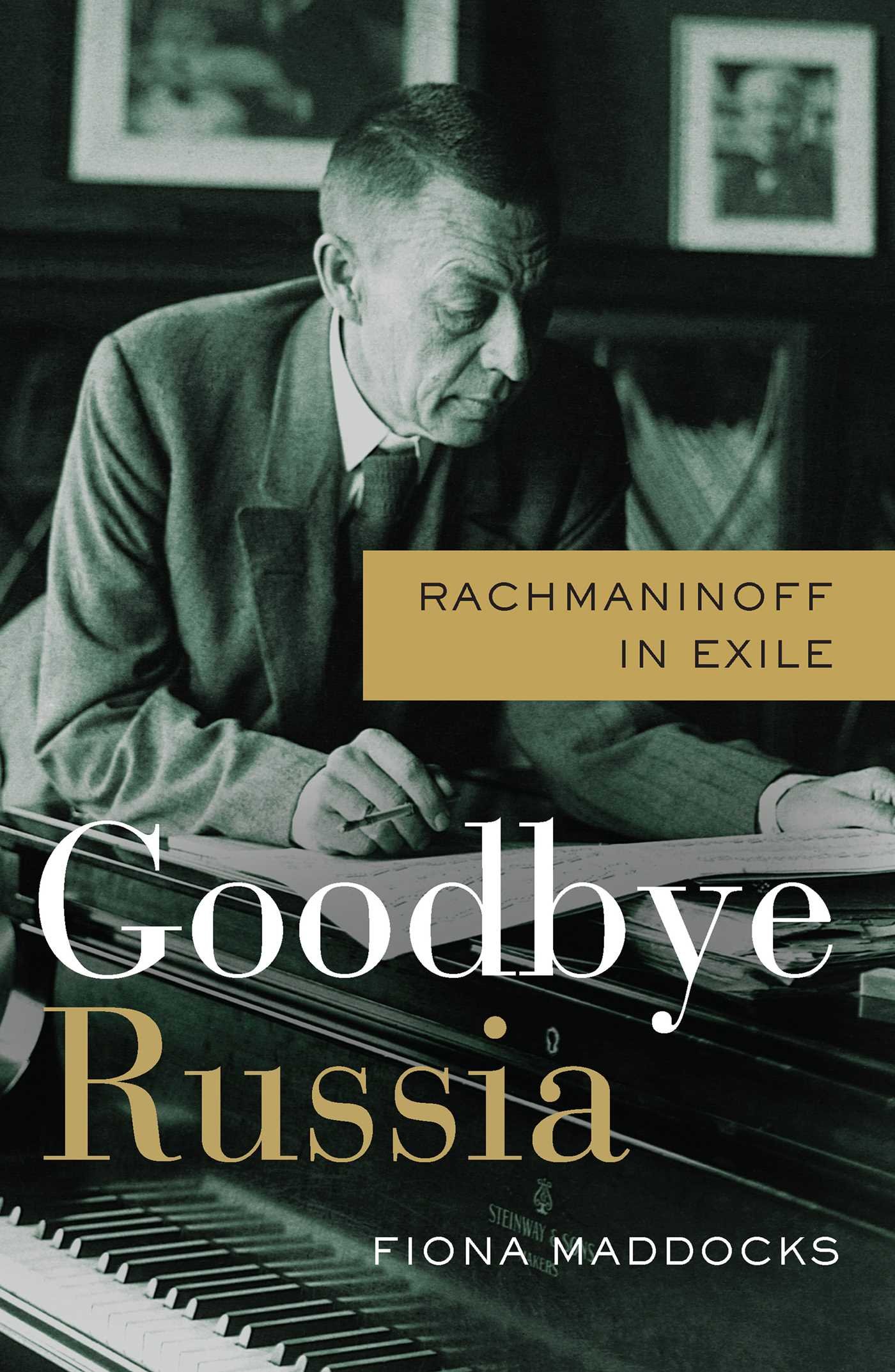

Goodbye Russia by Fiona Maddocks

/Goodbye Russia: Rachmaninoff in Exile

By Fiona Maddocks

Pegasus Books 2024

The great composer Sergei Rachmaninoff was born in imperial Russia in 1873, and since like all self-respecting Russian geniuses he was a precocious prodigy, he was already at the height of a flourishing career as a pianist, composer, and conductor when the Russian Revolution forced him to emigrate to the United States in 1918, where he lived for the rest of his life, with summers in Switzerland. He came to America in a teeming crowd of Russian musical titans, and they transformed the country’s classical music landscape for the better part of the 20th century while chaos engulfed the rest of the world.

Rachmaninoff died in 1943, and those long decades spent as an expat are the subject of Rachmaninoff in Exile by Fiona Maddocks, classical music critic for the Observer and founding editor of BBC Music magazine. She covers this quarter-century in a very fleet 300 pages that go heavy on the personalities and light on technical in-the-trenches musicology. Despite the fact that the Rachmaninoff she crafts is a courtly, fairly placid figure, these pages positively bristle with clashing personalities and brushfire vendettas. Some of these Russian exiles got along with each other better than others, but Rachmaninoff seemed to be broodingly resentful of all of them for one reason or another, usually dropping dark hints about complicated and unforgivable offenses in the shadowy pre-revolution days.

Predictably and rather delightfully, Maddocks is subtly partisan. She quotes, for instance, Stravinsky’s famous “catty remark” about how Rachmaninoff was “a six-and-a-half-foot tall scowl,” but she goes into far more detail when reporting what an evil little gnome Stravinsky himself was, quoting Romain Rolland: “He is small, sickly looking, ugly, yellow-faced, thin and tired, with a narrow brow, thin, receding hair, his eyes screwed up behind a pince-nez, a fleshy nose, big lips, a disproportionately long face in relation to his forehead” and adding, perhaps with a touch of asperity, “Today such remarks would have the lawyers in.”

Some Russian exiles fare a bit better than others in these pages. In addition to everybody else, for example, Rachmaninoff nurtured a brace of resentments against the renowned Boston Symphony Orchestra conductor Serge Koussevitsky, again often for obscurely-hinted offenses in their shared primordial Russian days. In reality, Koussevitsky was never anything but kind and supportive to Rachmaninoff - in the old world or the new – but that doesn’t stop Maddocks from sympathizing with her subject perhaps a bit too far:

[Koussevitzky] was, above all, a great supporter of Stravinsky, and asked him to compose a work in his wife’s memory. Stravinsky rejigged some music he had written, at Orson Welles’s behest, for an abortive film version of Jane Eyre. In his haste, the orchestral parts had not been corrected. The trumpet was notated in the wrong key. The premiere was a fiasco. Stravinsky apologized profusely but it appears Koussevitzky, reputedly not the most fluent of score-readers, was not aware of any problem.

Fortunately, Maddocks can also be sternly evaluative when it comes to her protagonist as well. She dutifully reports that the Pasternaks, father and son, weren’t wild about Rachmaninoff’s piano concerts (“he may as well have been sitting in front of a bowl of soup”), and she’s frank about the worldly side of her subject’s life. “He liked money,” she writes. “He needed it too, to support not only his family but also his long-term mistress, the Russian-born dancer and painter Vera de Bosset.”

The stress Rachmaninoff felt on the sidelines of the war is a dark undertone through much of this account. He had children in Europe, and one of his daughters was married to a man serving in the French army. As Maddocks relates, he told a reporter that “Each day I live in fear of a cablegram,” and could only get any real relief when he was working. As he sententiously put it: “Only when I am busy with music can I forget for a little while. It makes one’s own grief and anxiety easier to bear if one can believe he is bringing the solace of music to others who are troubled” (cf: the above statement about money).

One root cause of Rachmaninoff’s scowl might have been the fact that his art withered in exile, whereas that of Stravinsky (or even Koussevitzky) flourished. Rachmaninoff’s 3rd symphony and his Symphonic Dances are the only truly great works that come from his time outside of Russia, and the remainder of his compositions in exile contain a good deal of musical puttering around and some notation-equivalents of the all-purpose resentment that curdled the composer’s final decade. This makes it all the more remarkable that simple rancor plays so small a part in Goodbye Russia; Maddocks seems much more concerned with digging into daily concerns and personal realities. There are plenty of letters quoted here at pleasing length, plenty of reflections of the great man from the people around him – and our author’s own reflections, which are always both succinct and moving. “His gift was lyricism and melody,” she writes, “This was Rachmaninoff’s defining quality, his musical fingerprint.”

Readers will wish that Goodbye Russia were longer, but maybe that’s simply because the subject himself is so oddly appealing, so grim and yet so human. Maddocks has written a consideration fit to go on a shelf alongside Max Harrison’s terrific study of the composer from twenty years ago.

Steve Donoghue is a founding editor of Open Letters Monthly. His book criticism has appeared in The Washington Post, The American Conservative, The Spectator, The Wall Street Journal, The National, and the Daily Star. He has written regularly for The Boston Globe, the Vineyard Gazette, and the Christian Science Monitor and is the Books editor of Georgia’s Big Canoe News