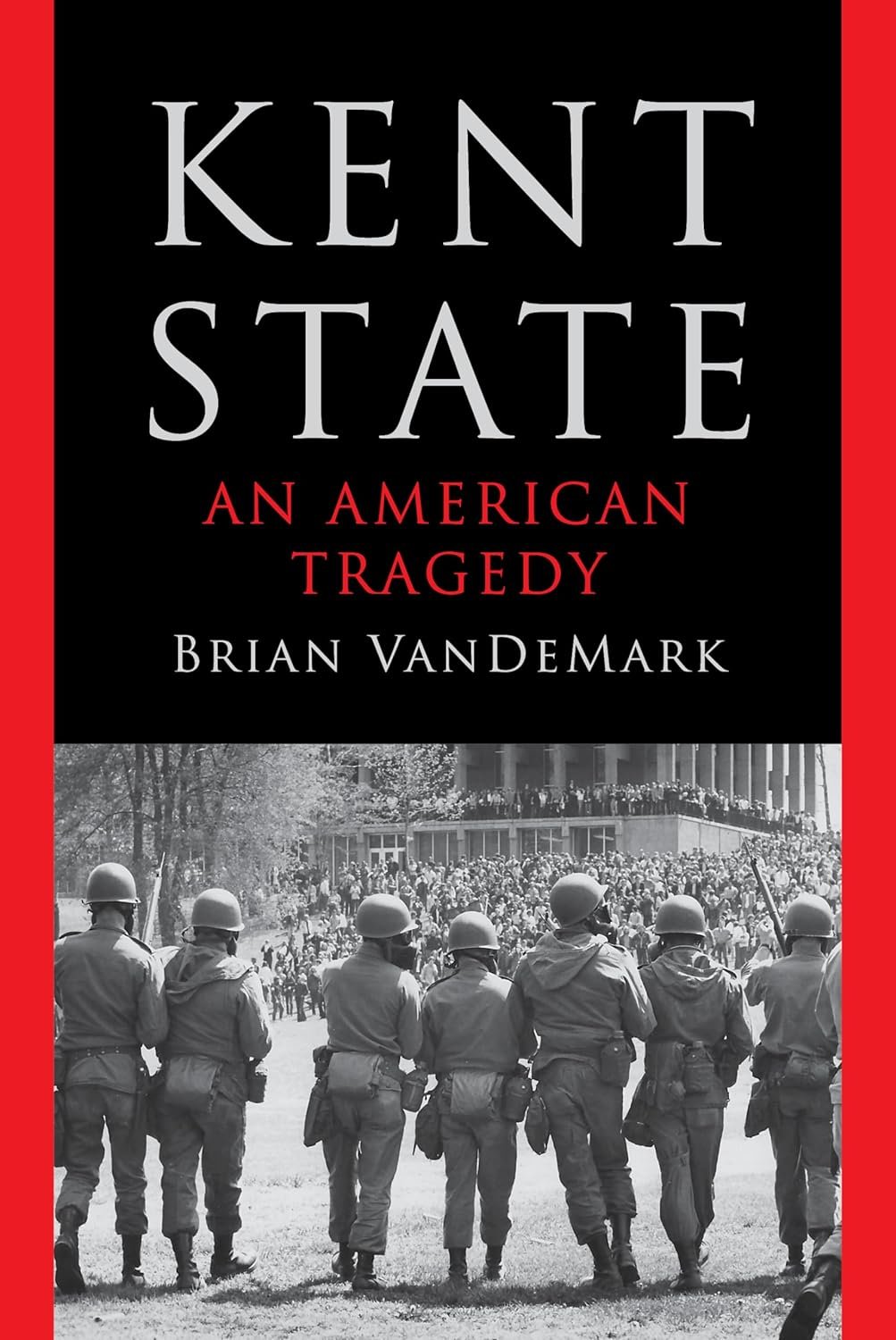

Kent State by Brian VanDeMark

/Kent State: An American Tragedy

By Brian VanDeMark

WW Norton 2024

The shooting of students on the campus of Ohio’s Kent State University on 4 May 1970, popularly known as the Kent State Massacre, has had the same sharply ambiguous fate that instantly befell the Boston Massacre two centuries before: it’s entered the zeitgeist. Thanks in large part to John Filo’s Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph of Mary Ann Vecchio kneeling beside the body of Kent State student Jeff Miller, the words “Kent State” has become a cultural shorthand for a whole suite of things, from the doomed valor of student protests to the casual brutality of armed law enforcement.

The zeitgeist is great for iconic immortality, but it can be very bad for historical accuracy. Most people have a mental impression of the Boston Massacre, for instance, that’s substantially inaccurate to the events of the day, but the Kent State massacre happened in the full light of modern TV reporting, with hordes of reporters descending on hundreds of participants and picking over every detail exhaustively.

There would seem to be little of value to add to that pile of documentation, but that doesn’t make the story itself any less compelling. Brian VanDeMark, who teaches history at the United States Naval Academy, adds to that familiar story in two main ways: he sifts through a huge amount of primary material not only on the event itself but also on its “tumultuous era,” and he pays the events the thoroughly justified compliment of letting the dark drama of the event mostly speak for itself. It’s true that his own prose can sometimes be a bit flaccid (“The time had come to confront the grown-up world of power,” goes one of many such passages. “It would be an eye for an eye, which they could not see eventually makes everyone blind”), but he fills his book with quotes that brim with the manic anger of the time. “I remember the rage setting in on me, and the frustration that we all felt because we couldn’t stop the war … what was in my mind was rage, pure rage,” he quotes one militant later recalling. “Vietnam had receded. Cambodia had receded. It was clear that the issue [now] was the guard’s occupation of the Kent State campus,” said a student. “It wasn’t an antiwar rally; it was a National Guard get-the-hell-off-our campus rally,” said another.

The National Guard is of course at the heart of the story, with its general bumbling, its curfews, its tear gas, and ultimately its illegal firing on unarmed US civilians. VanDeMark fleshes out his history with dramatic elements drawn en bloc from various sources, like the anecdote he takes from James Michener’s 1971 Kent State: What Happened and Why:

An African American professor sat in his office that morning waiting for his weekly conferences with students. One of Rudy Perry’s lieutenants entered and abruptly said, “Professor, you’ve got to get off this campus right now.” “What are you talking about?” “Off. Get off.” “Why?” “There are guardsmen out there. They have loaded rifles.” “What have they to do with me?” “They like to shoot blacks.” “What are you talking about?” “Professor, you may be an intelligent man. But there are some things you don’t know. I’m from Newark, New Jersey. And I do know. You get the hell off this campus.” The professor left.

Likewise that central visual moment, which VanDeMark sources to the 2000 documentary Kent State: The Day the War Came Home:

Moments later, Mary Ann Vecchio, a fourteen-year-old runaway from Opa-locka, Florida, who had long, flowing dark hair, was wearing jeans, a white scarf, and sandals, and had spoken with Jeff a few minutes earlier, knelt over his lifeless body. “I’ll never forget how I felt when I looked down and saw Jeff lying in a pool of his own blood,” she later said. “I was scared … I knew he was dead because his face was blown off …”

Kent State: An American Tragedy has a quasi-iconic feel all its own, the sense of being a masterful syncretization of the vast number of Kent State accounts that have preceded it. The event is still firmly lodged in the zeitgeist, refreshed every time the forces of the government become nakedly coercive, and in this book it has its careful, appropriately dramatic final word.

Steve Donoghue is a founding editor of Open Letters Monthly. His book criticism has appeared in The Washington Post, The American Conservative, The Spectator, The Wall Street Journal, The National, and the Daily Star. He has written regularly for The Boston Globe, the Vineyard Gazette, and the Christian Science Monitor and is the Books editor of Georgia’s Big Canoe News