No Strange Quirk of Fate

/Time-lapse photography is a miraculous thing. Like a superpower, it changes our relationship to the mundane, revealing life lived at a different pace. Desolate winter, for example, can become lush spring in seconds. Likewise, a teenager can age one day a second for four years (her hair tossing as if in a storm, the minutia of her life cascading across her bedroom walls).

When lovingly executed, time-lapse footage haunts and inspires. Details blur to give us impossible perspectives. Grander patterns and unconventional theories surface in the mind. No matter the subject, we see reflected the familiar elements of life. But what dances before us does so with a strange life of its own.

I find myself haunted and inspired regularly by the hundreds of Avengers comics shelved in my apartment. Published monthly by Marvel since 1963, the magazine features the exploits of Captain America, Thor, Iron Man and a cavalcade of other heroes. Flipping through them, I see a time-lapse of costumes changing across the decades. I see heroes facing challenges from the Civil Rights era to the Iraq War. Whatever we’ve lived, so have the Avengers.

With speedy fingertips and a practiced mind, I can jump to any point in the still-weaving tapestry. Issues of the Avengers from the 80s and 90s, my childhood, will be forever invested with the sweetness of youthful discovery. Those from the 60s and 70s are as transporting as old issues of Time, National Geographic, or even Abbey Road and Chinatown.

Taken together, however, an era of comics can transport to a place entirely their own. Writers Kurt Busiek, Roger Stern, and artist Carlos Pacheco celebrated this aspect of four-color literature in 1998, with a twelve-issue series called Avengers Forever. It features Rick Jones, former sidekick of the Hulk, coming under the protection of several heroes from different points in their own decades’ long saga. Brought together, for the first and only time, is a Captain America demoralized in finding his government corrupt, a Hawkeye armed with no trick arrows, only his wits, and Songbird, a former villain who will be an Avenger in the future. They must keep Jones safe from the Time Keepers, beings who fear that his ability to pull heroes across time will help mankind leave Earth and spread like a galactic plague.

Often twisted like a Moebius Strip, Avengers Forever stands as the ultimate love letter to Captain America, Hawkeye, and hundreds more. It is also a story that demonstrates superheroes’ surreal flexibility. To view a hero like Iron Man, linearly, in a time-lapse over the sixty years he’s been adventuring, reveals drastic changes. His 1963 debut placed him in the hands of Vietnamese Communists, where he built his bulky gray armor to escape them. Almost immediately, his armor was recolored red and gold, and streamlined. Then, a revision of his origin in the 1990s updated the backdrop to the Gulf War, and later, to Afghanistan, all the while making his armor sleeker and outfitted with current technology.

Such evolution makes perfect sense. Fans age, and to keep them buying comics as adults, stories must advance in realism, complexity and relevance. A peek at any hero in the time-lapse will show certain details adjusted to keep her from being juvenile or a complete anachronism (unless the plot requires it). After decades of adjusting, comics now compete with novels, television, movies, video games and sports for adult attention. And today’s Hollywood wizardry helps them to. Aerial fist fights, lasers fired from eyes, and much more have been convincing special effects in film for over ten years now.

But it’s the characters and their stories that have kept superheroes worth filming. This month’s release of an Avengers movie couldn’t be more hotly anticipated by fans. Directed by Joss Whedon, creator of Firefly and Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog, it’s heralded by five prior summer blockbusters: Thor, Captain America, The Incredible Hulk and both Iron Man films. The Avengers, however, is a cannon shot announcing not only summer, but also a fresh way to immerse viewers in long-form entertainment.

Ten years ago, Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy, filmed all at once and hugely successful, transfigured the movie-going experience. Slavishly executed in the spirit of the books, it resulted in equally slavish fan loyalty. Dozens of genre properties were, and have since been, considered for similar treatment, including The Matrix, The Chronicles of Narnia and the Harry Potter series.

With five tie-in films preceding it (each concluding with a teaser scene), The Avengers has brought new vitality to franchise film-making. Yet, in the time that Marvel has spent establishing its big-screen Universe, mindless witticisms have abounded. Said in an Iron Man 2 review, “[It] seems chiefly intended as a placeholder for its next dozen or so sequels.” Said of Thor, with contempt, “…a sore spot is the recurrence of Marvel’s awkward and greedy attempts to build audience and pound the drum for future films like The Avengers.”

As a comic reader for twenty-two years, and someone for whom The Avengers franchise has been carefully tailored, let me summarize for those critics too hip for their homework. The audience for an Avengers film has existed for decades. The material has just been too enormous a proposition for Hollywood until now. Between the pages of a comic series, deft writing and art can introduce six different heroes, flesh them out with short solo adventures, and then have them all band together by the end to face a larger menace. This is what The Avengers franchise has been doing since the first Iron Man film.

Still, to ask with genuine curiosity, what makes the Avengers worthy of such extravagant film-making? The answer lies in Marvel’s tangled history with their competitor, DC, and the comic book’s evolution from childhood diversion to artistic statement.

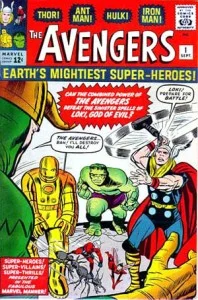

At the end of The Avengers first issue, Stan Lee called their assemblage a “strange quirk of fate.” What did he mean? We’ve seen the mutant X-Men on screen, living at a school, warring with other mutants over ideals. The Fantastic Four, also film stars, are a family, and primarily explorers of esoteric ideas and parallel dimensions. But the Avengers exist because we need them. And we, across thousands of comic pages, has variously meant the United States, the Earth, the Milky Way, and the Twentieth Century. As a team, they can scrimmage against any threat, no matter the size. The comic’s current roster encompasses most of the Marvel heroes who usually stand alone, such as Luke Cage, Daredevil and Spiderman. They’re a small army.

Like most of today’s successful Marvel titles, however, The Avengers began cautiously, spinning out of writer Stan Lee’s mind because DC had found winning sales with the Justice League of America, a team comprised of the publisher’s most popular solo adventurers. In the early 1960s, Marvel still flogged the dying genres of horror and monster comics. With brilliant transitional savvy, Lee and artist co-creator Jack Kirby first gave us The Fantastic Four, featuring The Thing, surly and built of orange bricks, the Human Torch, an impetuous teenager when not covered in flames, and lovers Sue Storm and Reed Richards, the more photogenic half of the team. They didn’t have secret identities like Superman’s Clark Kent. But the comics world came to know them, adoringly so, as Marvel’s first family.

Next in the Cambrian Explosion of Heroes that was Stan Lee’s creative output during the 60s, came the Hulk, Spider-Man, Thor, Iron Man, Antman and the Wasp, Daredevil, Dr. Strange and the X-Men. Designed by Steve Ditko and Jack Kirby, these characters, unlike their DC counterparts of the time (The Flash, Green Lantern), leapt from the page, crackling with energy.

And it is a wonderfully specific energy, born of studying one’s competition in minute detail. Despite his affability during interviews and film cameos, I picture Lee and tireless innovator Kirby (who learned speed working in animation at Fleischer Studios in the late 30s) dissecting a Batman comic with penknives to itemize its dozen faults.

To be fair, the faults had one major source. The 1954 “Comics Code” prevented heroes from corrupting children with adventures that were either dangerous or sexy. This sent DC swerving into bizarre narrative territory, going sharply out the way to prove Batman and Robin were nothing more than platonic do-gooders. Bat-Woman, Ace the Bat-Hound, and the impish Bat-Mite were introduced during this era. Himself barrel-chested and grinning vacuously, wacky Uncle Batman ushered readers through the “The Peril at Playland Isle” and “The Olympic Games of Space”, all while respecting authority and never losing a fight.

Thoroughly insane though the stories were, they offer modern sensibilities a buffet of psychedelic charm. The real problems began when various heroes left their own comics to become the Justice League of America. Fatherly figures such as the Flash and Green Lantern were imbued with little enough personality to start with. Their civilian lives were primers for young men on holding high-paying jobs and the proper courting of women.

Then, once inside the rollicking “team-up” world shared with Wonder Woman, Superman, Martian Manhunter and others, they became interchangeable. The adventures constructed for these marquee heroes almost never required them to fulfill their roles. The villains, if not mischief-making out of boredom, only wanted to rob banks, vaults and galleries. The actual narrative mechanics seem, to adult minds, to be have been conceived in jest. In one tale where the Justice League fights alongside their alternate Earth counterparts, the Justice Society, the evil Fiddler battles Hour-Man and the Atom in a natural history museum. Playing his enchanted fiddle, the villain animates a stuffed polar bear, a gorilla and a pterodactyl (so far, so good). Held back by the gorilla, Hour-Man says, “Atom- can you manage to hurl that winged reptile in my direction?” The Atom does, and the pterodactyl’s beak hits his partner’s belt buckle, activating a radio BLEEP that disrupts the Fiddler’s attack.

Multiply that devilish instance of, “Let’s have THIS happen!” by twelve, and you have thick rainbow mulch masquerading as entertainment. Thankfully, Stan Lee knew adults enjoyed comics too. The Fantastic Four immediately revealed its protagonists to be real people who argued, acted on emotion, and frequently questioned motives. The Avengers sees the Earth’s Mightiest Heroes come together as Loki, Thor’s half-brother, manipulates the benign but hideous Hulk into attacking a train. The Asgardian God of Mischief, however, doesn’t realize that news reports have called several adventurers to action. In the end, Ant-Man and the Wasp (whom readers may suspect of contributing the least) suggest the heroes stick together, since they each contribute something unique to the team.

Stan Lee’s dramatic formula was anything but formulaic. The use of characters’ essential personalities to propel action-filled plots hit the mark nine tenths of the time. He kept their motives real and their travails sustainable for as long or short a period as seemed reasonable. Peter Parker, the teenaged Spider-Man, fears for his frail Aunt May’s health for years. The Hulk, after the Avengers’ second adventure, quits because a creature called the Space Phantom takes his identity, causes chaos, and pits the team against him. “I never suspected how much each of you hates me,” says Hulk to his teammates, once the battle ends. “I could tell by the way you fought me… by the remarks you made.” This couldn’t have happened in the same era’s Justice League.

Captain America, created by Kirby and Joe Simon in 1941, is soon found by the Avengers floating in ice. He’s the final piece of the puzzle for about a year (through June, 1965), during which the team faces such menaces as Kang the Conqueror, The Masters of Evil, and Wonder Man. Then, due to personal entanglements elsewhere, everyone walks away from the team except Captain America. To underscore Cap’s charisma, Lee has him reassemble the Avengers with reformed villains: Hawkeye, and mutant siblings Quicksilver and the Scarlet Witch (issue sixteen, 1965). Also in this time, the blocky elegance of Kirby’s people and buildings made way for Don Heck’s slender, sketchier imitations (issue nine, 1964).

Heart-felt characterization coupled with the unexpected seems basic today, but DC would spend the 60s catching up. By then, Marvel was broadening the canvas and producing dashingly potent material. Once Lee had established an interlocking realm, where sea king Sub-Mariner could menace the Fantastic Four one month, and then bring the details of that battle to the X-Men later in the year, grandiosity began suffusing the Marvel Universe. Communist overlords, jungle-based Nazis and Asgardian rogues, all innovations themselves, risked growing stale with repetition. Then, in 1966, cosmic storytelling became a full throttle endeavor. The planet-devouring Galactus appeared in The Fantastic Four, and a young man named Roy Thomas began writing The Avengers.

Coming to the scripting job as a fan, Thomas revered the characters and knew exactly who had done what, and in which book, since their inception. He continued the plot threads that Lee, now editing, had in place. But once those threads were resolved…

If Lee’s stories seemed to defy gravity, Thomas’ ignored it. During a seven year stint, the younger man ensnared an always-rotating roster of Avengers in finely-tuned space operas. His partner in excellence was John Buscema, a big man whose adaptation of Kirby’s style resulted in a big, burly remastering of The Avengers.

Buscema drew slanted panels, clawed hands, and pulsing white eyes from shadowed brows. A close-up of the evil mutant Magneto illustrates his insanity well before a member of the U.N. announces it. Buscema and Thomas also began to sculpt entrancing, gothic opening pages that rivaled the comic’s cover. One such page proclaims, “Behold… the Vision!” It introduces this era’s best tale, featuring the debut of the Vision, a synthetic humanoid, who joins the Avengers to battle the villainous Ultron. Afterward, when they ask him to join the team, he says, “Excuse me… please… I shall return within a moment.” Iron Man disputes this reaction, and Hank Pym tells him, “If you saw his eyes right now, I’m sure you’d learn that… even an android can cry!” This is clearly meant to resonate more with adults than children (eventually, there won’t be much to entertain a child at all).

By the early 80s, psychedelia and cosmic-themed fairy tales, like everywhere else in pop culture, had run their course in comics. Thomas and Buscema had moved on, making Marvel’s adaptation of Robert E. Howard’s Conan spectacular, and their shoes were never properly filled. DCs creative triumphs were the brainy Swamp Thing, by Alan Moore, and the energetically executed Teen Titans, by Marv Wolfman and George Perez. Marvel folded up their telescope and closed the era by executing its titular hero, Captain Marvel, in 1982. Did they dissipate his corporeal structure, or devolve him into an amoeba? No. They gave him cancer.

And so, Earth’s Mightiest Heroes returned home to the grim realities of the Cold War. Writer Roger Stern, joined first by Al Milgrom’s mediocre pencils, then by John Buscema once more, advanced a plot in which the humanoid Vision takes over the world’s computer systems to enforce peace. Instead, he instills deep dread, which down the road leads to his dismantling. This era also sees the Masters of Evil ruin the Avengers with vicious calculation, demolishing Tony Stark’s Fifth Avenue mansion, crippling demi-god Hercules and butler Jarvis in the process. This tone successfully brought our heroes down to Earth, revealing them to be not just flawed individuals who made it through the day, but friends for whom we should fear.

Meanwhile, DC had launched the limited series Watchmen, set in an alternate 80s still run by Richard Nixon. There, the complex characterization of Dr. Manhattan, Nite Owl and the Silk Spectre reached heights nobody dreamed possible by a comic. Yet it was only one punch of two thrown by DC in 1986, and when Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns gave us an aging Batman who nearly beats the Joker to death, it fully repackaged a childhood icon for adulthood (also, Moore and Miller’s stories were self-contained, set apart from the standard continuity of the DC Universe; they became some of the first graphic novels sold in bookstores, where browsing adults might stumble upon them).

Before true adulthood in comics, however, the growing pains commenced in earnest. Grit, gore and their sudden advent by the truckload did several things to the industry. First, they led to the formation of Image, a company founded in 1992 by the young and the restless within Marvel’s talent pool. Splitting from the professional environment of kept deadlines and challenging stories, artists like Todd McFarlane and Rob Liefeld put out ambitious work sporadically (brutally violent team comics like Bloodstrike, Youngblood and Brigade were all the rage). To compensate, every other issue had a reflective foil or gate-fold cover typically reserved for anniversaries. Soon, people wanted to collect these single comics, not necessarily read them.

Second, epic violence made killing characters obscenely lucrative. DC killed Superman in 1992, bagging the comic in black mylar and including an S armband and Daily Planet article. Everyone wanted a copy, or ten, sitting next to their signed baseballs and action figures.

Could Marvel trump such a stunt? They certainly tried, using their large family of ultra-popular X-Men titles to foist twenty-part sagas, trading cards and hologram covers onto fans. Writer Chris Claremont had shepherded the X-Men to greatness in the 70s and 80s. Marvel squandered this by flooding the market with them, and writing stories that inflicted the X on their entire Universe.

The Avengers family of titles (including Captain America, Iron Man and West Coast Avengers) held their own, even when they split down the middle ethically. In the 1992 tale Operation Galactic Storm, conceived by Mark Gruenwald, Bob Harras and Fabian Nicieza, alien races known as the Kree and the Shi’ar go to war. When the use of a nearby star-gate endangers Earth’s sun, the Avengers intervene. Eventually, they witness the detonation of a Nega-Bomb, which devastates the majority of the Kree Empire. When they learn that the race’s own Supreme Intelligence, an organism representing the sum of their culture, is responsible, the Avengers vote on its execution. Despite a decision for clemency, Iron Man leads a rogue contingent that successfully kills the creature. The Avengers loyal to Captain America, who is typically written as the United States’ conscience, refuse to participate.

But the moral murk of anti-heroes on parade couldn’t last forever. The next great era of The Avengers, free of reflective covers and controversy, came in 1998. Kurt Busiek, child of the 70s, and George Perez, an up-and-comer in the 70s, did everything right in their three year run together. Combining Stan Lee’s gift for personal drama with Roy Thomas’ tight continuity and cosmic flair, they initially assembled every hero to ever grace the roster. From there, after pitting the Avengers against Morgan Le Fey, of Arthurian legend, Busiek and Perez streamlined the team to an essential seven icons,whose mix of powers and personalities is difficult to top: Captain America, Iron Man, Hawkeye, the Scarlet Witch, Vision, Thor and the troubled Warbird (originally Ms. Marvel from the 70s), whose alcoholism is addressed in the first story arc. The creators also bring in new characters like Silverclaw and Triathlon, and classic villains such as Ultron, Grim Reaper, and the Squadron Supreme.

Busiek and Perez channeled their love for The Avengers into a full-blown rejuvenation of the material. Since their run, no one creative team has matched their enthusiasm. Marvel’s main goal since the 2006 Civil War miniseries, which once again pit Captain America against Iron Man (echoing the United States’ liberal/conservative split) has been to ramp up the Avengers franchising. Recent books have included Young Avengers, Avengers Academy, Dark Avengers, The Mighty Avengers.

Which begs the question: where can the fledgling fans turn today, their curiosity peaked by Marvel’s formidable march through Hollywood? Is there a proper access point into the genre that’s defined this past decade the way over-the-top action did the eighties, or indie films the nineties?

By Odin’s Beard, of course there is! But with the easy flow of ideas among comic publishers (and throughout science fiction culture at large), this access point, unsurprisingly, is not a Marvel title. It’s a DC title, published under the now defunct WildStorm imprint, called The Authority.

Created by writer Warren Ellis and artist Bryan Hitch in 1999, The Authority redefined superheroics for the twenty-first century. And it did so by perfectly balancing all of the major motifs of the last twenty years, such as geopolitical relevance, brisk, brutal action, and dynamic character interaction. However, unlike Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns before it, this comic performed a dual rout on its enormous, successful competitors that any third party candidate for the U.S. Presidency would envy.

The premise of Ellis and Hitch’s baby is an epic tease: seven iconic heroes saving the world from threats that no single hero can. Seeing this on the shelf, new and seasoned readers alike asked, “Can this offer me anything that The Avengers and Justice League don’t?”

Absolutely. Ellis and Hitch raise the superhero genre to new heights of realism. Their characters, analogues of Superman (Apollo) and Batman (the Midnighter) among them, kill brutal dictators instead of deposing them. They teleport in and out of countries under alien attack, engaging in aerial dogfights reminiscent of World War II. They also express very human awe at the lives they lead. In one scene, the Engineer (a woman with liquid machinery for blood who rivals Green Lantern in the “Does It All” category) lands on the moon with her teammate Apollo. She can only grin, speechless. “Touchdown,” says Apollo. “The Engineer has landed.”

And then there’s the missing sound effects and exposition boxes, quickly forgotten by the reader as The Authority absorbs him. A lack of the first requires that the artist convey even the tiniest action, which Bryan Hitch surely prefers. He is arguably the artist of his generation, with a love for widescreen, impossibly detailed panels that would be marred by red letters zigzagging across them.

The lack of the second splits a need for clarity between the writer and artist. Exposition boxes, after all, typically set the scene, catch the reader up on details, or provide a character’s thoughts. But the WildStorm Universe was established in the early nineties. It was an underused place, without fifty years of history to respect in every story. This liberated Warren Ellis to strip his tales down tonally to the bare essentials (think how much more visceral a horror film feels without music reminding you that it’s just a film). He then created no-nonsense villains and ballsy threats that destroyed Moscow, Tokyo and London. He even gave us tenderness as we never expected it, as the Midnighter, fearing for Apollo’s life, kisses his cheek.

During The Authority‘s stylistic coup of the comic industry, which made reading a comic more like watching an action movie than ever before, both major publishers were paying attention. One of them, as usual, was readier to act than the other.

Marvel launched the Ultimate Universe in 2000. Starting with the titles Ultimate Spider-Man and Ultimate X-Men, the publisher took their most popular characters and put them in a pocket realm, making them younger and divorcing them from decades of back-story (attempted in 1996, with the Avengers and Fantastic Four, Heroes Reborn proved disastrous). With a fresh slate, hipster writers Brian Michael Bendis and Mark Millar told tales that firmed up the best of Marvel’s original continuity without being shackled to it.

The books succeeded massively, bought by people new to comics and impressed by the Spider-Man and X-Men films. They merely lit the runway, however, for the The Ultimates, a comic that captured this last decade’s militarist zeitgeist to a fault. Written by Mark Millar, drawn by Bryan Hitch, it essentially gives Captain America, Thor and Iron Man an Authority makeover.

Hitch painstakingly created a New York you can step into. He also illustrated real people frequently, as favors to fans, but also in courtship to Hollywood. The eye-patch wearing Nick Fury, a Caucasian for fifty years of Marvel continuity, is drawn as Samuel L. Jackson (artists have done this before, most notably Mike Deodato Jr.’s Norman Osborne, Spider-Man foe the Green Goblin, modeled on Tommy Lee Jones; but this is the sole instance of flesh and blood reciprocation). President Bush, Larry King and Elizabeth Shannon also appear to bolster the comic’s realism. The first seven issues, before deadlines forced Hitch to rush, are a flawless visual feast.

Less flawless, unfortunately, is the writing. Millar followed Warren Ellis in abandoning exposition boxes. Instead, characters speak in long, stilted paragraphs that bully plot details forward. Successive readings also highlight Millar’s nasty tick of having characters slap each other with insults like, “you idiot,” and “you moron.” Sometimes this proves uncomfortably effective, such as the scene where the engaged Hank Pym and Janet Van Dyne domestically abuse each other. Other scenes, like when U.S. soldiers help Iron Man back into battle, then push down a young boy cheering him on, reveal a gratuitous cynicism that taints the entire comic.

But The Ultimates didn’t just marry Mr. Jackson to the pivotal role of Nick Fury. The comic is a visual blueprint for The Avengers‘ film franchise. Costumes are found nowhere in its pages, only fully functional uniforms, complete with combat boots and protective padding. Lamentably lost is Hawkeye’s purple circus attire, which fits the cocky marksman as well as Spider-Man’s trademark red and blue suit. Practical streamlining has also removed Thor’s helmet and the wings from above Captain America’s ears. Which is fine. The X-Men, after all, had to wear biker jackets around L.A. Since then, moviegoers have become much more forgiving of spandex. The time-lapse view always has been.

This month’s blockbuster also borrows a key plot element from The Ultimates in the alien Chitauri. That Whedon has lanced the material of Millar’s psychic backwash is a certainty. His television shows Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel were nothing if not gleeful homages to the best that Marvel has offered down the years. Also, Disney now owns Marvel, and the comics themselves are in the midst of an “Age of Heroes” where swashbuckling, not political statements, reigns supreme.

The Avengers competes primarily this summer against Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight Rises. This means that publisher DC moves into 2013 with one Justice League character wrapping up a trilogy and Superman ready to reboot. Undoubtedly, they have been paying close attention. DC has seen the interwoven Marvel Universe written large, in all its hi-definition glory. Known as the Distinguished Competition, they are nothing if not daring. When they eventually come up from behind, they’ll prove we haven’t seen everything yet.

Justin Hickey was an editor at Open Letters Monthly, and writes regularly for Kirkus Reviews.