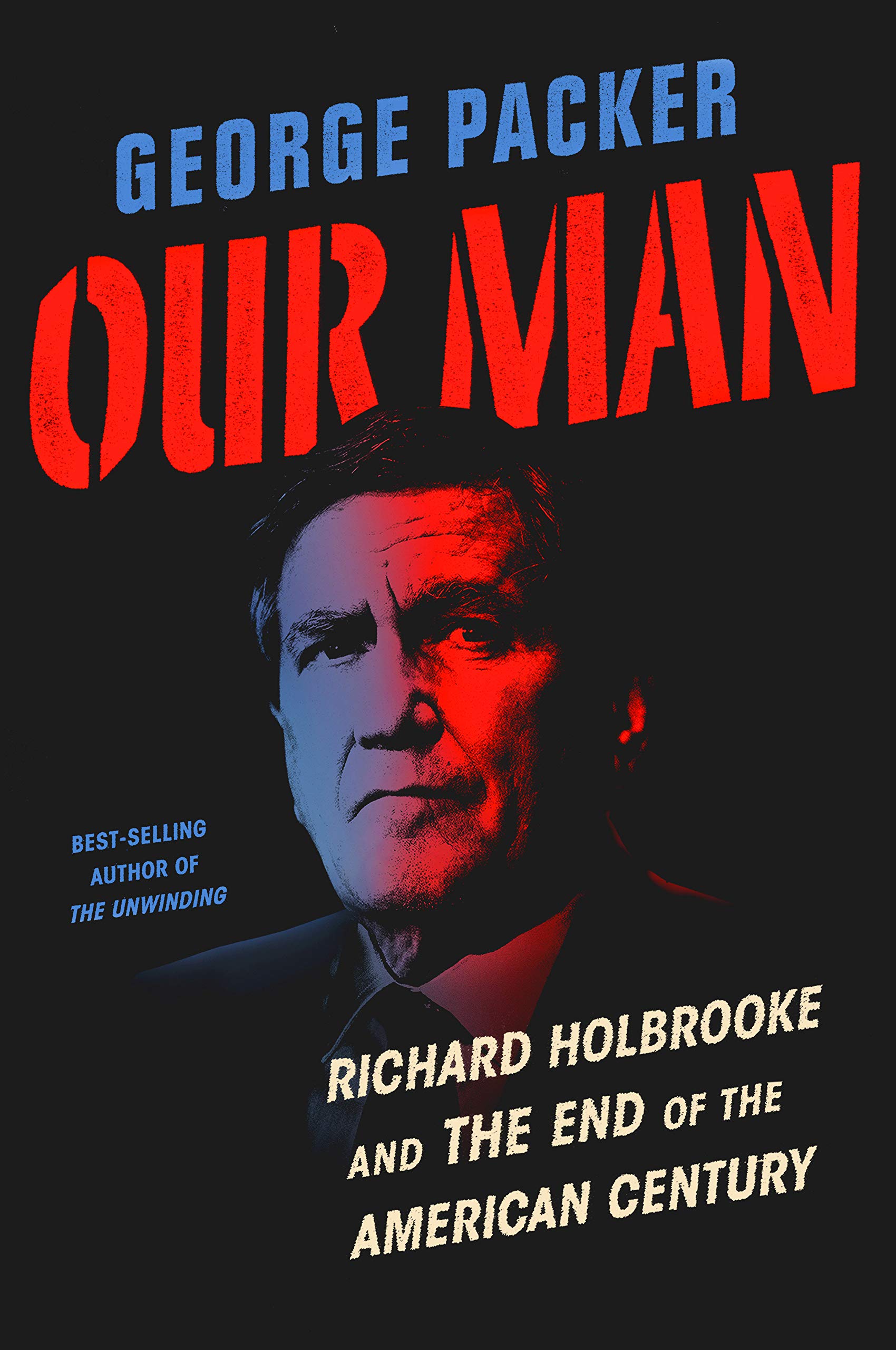

Our Man by George Packer

/Our Man: Richard Holbrooke and the End of the American Century

By George Packer

Knopf, 2019

It’s probably fitting that a public servant like the late Richard Holbrooke, bluff, garrulous, and unconventional, should draw a book like George Packer’s latest, Our Man: Richard Holbrooke and the End of the American Century, which is every bit as bluff, garrulous, and unconventional as its subject. Packer is a staff writer for The Atlantic and the author of the brilliant The Assassin’s Gate from 2005, and right at the start in Our Man he makes the dodgy but wise rhetorical choice to pitch the whole thing, 500 blustering, voluble, mesmerizing pages, as a patented Dick Holbrooke stemwinder, the kind of virtuosically swaggering story that the man himself used to uncork at Joe and Stewart Alsop’s Georgetown congeries half a century ago. The echo of those stories and countless others told in State Department meeting rooms and on endless late night phone calls sounds even in the book’s opening lines, which could have come straight out of a John Buchan novel: “Holbrooke? Yes, I knew him. I can’t get his voice out of my head.”

The extent to which this kind of posturing is or isn’t slightly ridiculous is exactly the metric that governed Holbrooke’s entire career as a diplomat, and all his questions and quibbling and occasional triumphs. There was plenty of all of that in Holbrooke’s career, from petty interdepartmental squabbles that make everybody (but especially him) look bad to his signature success, the hammering-together of the Dayton Peace Accords in 1995, opening a path to peace in war-torn Bosnia. Holbrooke was the author of long memos that actually make gripping reading; he was a perennial not-chosen candidate for Secretary of State, and he was a foreign affairs advisor to multiple presidents and presidential candidates. He was always the most memorable person in any room, mostly because he always wanted to be and would do what it took to make it happen.

“He had long skinny limbs and a barrel chest and broad square shoulder bones, on top of which sat his strangely small head and, encased within it, the sleepless brain,” Packer writes. “Ideas mattered to him, but never for their own sake, only if they produced solutions to problems. The only problems worth his time were the biggest, hardest ones.”

Holbrooke, needless to say, would have loved this kind of writing about Holbrooke, just as he would have publicly disavowed but privately devoured astonishing lines like these: “There was an air of carelessness about him, but when he looked straight at them with the full power of his ice-blue eyes, his frank and playful intelligence, women felt seen and known and were drawn to him … He was an attentive lover, without kinks.”

Our Man follows this attentive lover through every stage of his complicated life, always lightly or tightly mapped onto the course of America’s decline on the world stage. “What’s called the American century was really just a little more than half a century, and that was the span of Holbrooke’s life,” Packer writes. “The thing that brings on doom to great powers, and great men - is it simple hubris, or decadence and squander, a kind of inattention, loss of faith, or just the passage of years? - at some point that thing set in, and so we are talking about an age gone by.”

The wistfulness is loud and clear, here and everywhere in Our Man, perfectly reflecting the ‘ah for the good old days’ late-night attitude of the man himself and constantly dramatized in anecdotes that subtly (or not) vilify just the kind of squeaky-new backstabbing teachers’ pets who privately infuriated Holbrooke whenever he let himself think about subjects so small (pace Packer, this was almost all the time). Packer is extremely, almost alarmingly good at putting such moments before his readers:

[President Obama] asked his advisors, “Who’s going to talk to Holbrooke?” The assignment went to Denis McDonough. Every president needs a loyalist who doesn’t care what anyone else thinks as long as the boss has his back, which gives his actions a higher blessing than ordinary morality. McDonough had been a student at Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service when Holbrooke was negotiating peace in Bosnia. But he summoned Holbrooke to the White House and subjected him to a finger-pointing rebuke. Winning the trust of the president is a priceless achievement no matter what else you haven’t done, sending outsized power straight to your head.

Richard Holbrooke died suddenly in December of 2010 - abruptly, in mid-sentence, going full-throttle, just as he always seemed to be living - and the portrait Packer has crafted of him is a bizarrely hypnotic thing, equal parts cynicism and hero-worship, always managing to be both vastly friendly to its subject and brutally assessing. “So much thought, so little inwardness,” he writes with telling accuracy about Holbrooke. “He could not be alone - he might have had to think about himself.”

Our Man is a very different book from The Unquiet American, the Holbrooke book Derek Chollet and Samantha Power wrote almost a decade ago; it’s effortlessly better written, yes, but also far more personal - “Holbrooke? Yes, I knew him” - and far more unapologetically skewed to the curiously dynamic worldview that so often made Holbrooke indispensable to those with more power but less clarity. The book captures the man as no book is ever likely to do again; this is an accomplishment and also a precaution.

—Steve Donoghue is a founding editor of Open Letters Monthly. His book criticism has appeared in The Boston Globe, The Wall Street Journal, The Spectator, The Washington Post, and The American Conservative. He writes regularly for The Vineyard Gazette, and The Christian Science Monitor. His website is http://www.stevedonoghue.com.