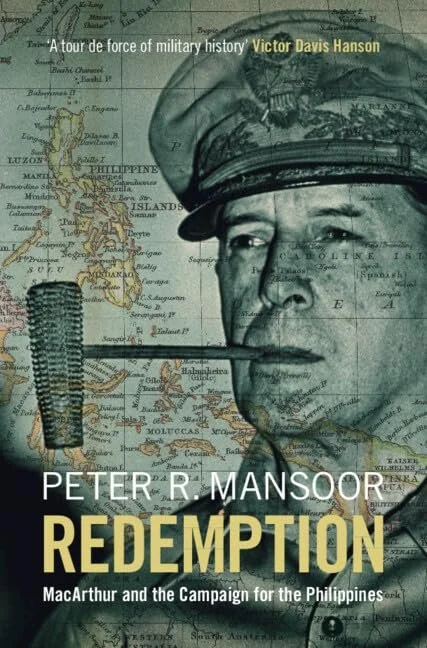

Redemption: MacArthur and the Campaign for the Philippines by Peter Mansoor

/Redemption: MacArthur and the Campaign for the Philippines

By Peter Mansoor

Cambridge University Press, 2025

Peter Mansoor’s Redemption: MacArthur and the Campaign for the Philippines is a superb book, a master class for one of the Second World War’s great campaigns and a measured consideration of one of its most difficult personalities. General Douglas MacArthur and his operations to retake the Philippines from the Japanese, who had defeated him there in 1942 (hence the title, Redemption), are rich topics for disputatious historians. Between MacArthur’s personality, reputation, and ego – any one of which seemed independently capable of blocking out the sun - as well as the nature and efficacy of the campaign itself, it requires some effort not to be utterly vociferous in one’s evaluations. Take the plain but authoritative writing of Max Hastings in his book Inferno:

The Filipino people whom MacArthur professed to love paid the price for his egomania in lost lives – something approaching half a million perished by combat, massacre, famine and disease – and wrecked homes. It was as great a misfortune for them as for the Allied war effort that neither President Roosevelt nor the US chiefs of staff could contain MacArthur’s ambitions within a smaller compass of folly. In 1944, America’s advance to victory over Japan was inexorable, but the misjudgments of the South-West Pacific Supreme Commander disfigured its achievement.

Mansoor’s ability to do the basic job of providing a good sweeping history of the Second World War in the Philippines while implicitly reevaluating severe assessments like those of Hasting’s results in nothing short of a virtuoso performance.

While the subjects of MacArthur and the Philippines are inseparable, they are not identical; and it is in part his handling of this fact that makes Mansoor’s book so expertly done. This is most conspicuous in the dedicated chapter and recurring attention given to the invaluable resistance groups, which he introduces with a rare bit of authorial snark: “Not everyone had to return, because not everyone had left.” Indeed, he maintains this sensitivity through to the end by giving his final words to the Filipinos and not to MacArthur. But it is borne out in other ways too, notably in the credit he happily gives to Robert Eichelberger, one of the best and comparatively unknown Allied generals. Eichelberger took his Eighth Army, which by 1945 had become one of the most exceptional armies the world has seen, and concluded the Philippines campaign as a maestro of amphibious warfare:

Eichelberger had a distinguished career in the Pacific War, rescuing operations gone amiss at Buna and Biak and outmaneuvering Japanese forces at Hollandia and on Mindanao. But his crowning achievement was the broader Visayan-Mindanao campaign, which liberated much of the Philippines and alleviated the suffering of the Filipino people under Japanese occupation at a modest cost in blood and treasure. This was an amphibious blitzkrieg, with Eighth Army conducting thirty-eight amphibious landings in forty-four day – nearly one a day – from February 19 to April 3, 1945, earning for it the nickname “Amphibious Eighth.”

But let us return to the broader campaign and central purposes of this book, avoiding if we can any hackneyed terms like ‘tour de force.’ As an account of a military saga, Redemption is wonderfully detailed without blunting its own narrative momentum. From the catastrophic loss of the Philippines - made certain by the US government’s unwillingness to appropriately equip them, made worse by MacArthur’s poor planning and tactical sense, and made tragic by the surrender and treatment of starving American and Filipino soldiers under General Wainwright who would find themselves on the infamous Bataan Death March – to the forming of MacArthur’s “Bataan Gang,” the epic centerpieces at Leyte and Luzon, and the campaign’s final conclusion, Mansoor adroitly modulates between the strategic, tactical, and operational levels, guaranteeing that the reader knows what happened, why it happened, and how it happened.

A good moment of this, and showing MacArthur’s definite strengths (still tinged by his inevitably angling), is when Mansoor details MacArthur and his co-equal in the Pacific, Admiral Chester Nimitz, making their separate strategic cases to President Roosevelt in Hawaii:

MacArthur then laid out his case for liberating the Philippines, and his heart was definitely in his proposed strategy. Japan’s line of communication to the Dutch East Indies could be severed from Luzon as easily as from Formosa [the course argued for by Nimitz], while leaving 300,000 Japanese troops (and their supporting air-power) untouched in the Philippines would entail an unacceptable element of risk should the Americans bypass Luzon in favor of invading Formosa. The Imperial Japanese Navy would be able to strike the US fleet near Formosa under the cover of land-based aircraft. The loyalties of the Formosan people, who had been subjects of the Japanese for half a century, were also suspect in his eyes, which made the island a less than ideal jumping off point for an invasion of Japan. The Filipino people, on the other hand, would overwhelmingly support the American liberators of their islands – MacArthur was sure of that. . .But MacArthur’s most important arguments were moral and political. The United States, in his view, had failed to support American and Filipino troops on Bataan and Corregidor, and if it were to now forsake the Filipino people and American prisoners of war and internees a second time, America would consign untold numbers to their deaths through starvation and suffer a grievous blow to its prestige in Asia.

Along with everything else Mansoor does in Redemption, at its core the book is a persuasive reassessment of the strategic and moral cases for the Philippines campaign that places General Douglas MacArthur as the central contemporary advocate for those points as well as the central contemporary object of their achievement. It is so often too easy to read MacArthur as basically an overgrown adolescent with a massive IQ. Mansoor makes a good case he was other things too, albeit in addition.

If it is not too awkward a punctuation in review, a final observation seems in order during this 80th anniversary of the end of World War Two: perhaps for reasons of geographic familiarity, maybe for other reasons of military interest, the different campaigns of the Pacific Theater of World War Two do not seem as readily present in the collective Western imagination as those of the Europe Theater. Far more easily do we picture Hitler touring Paris, or the battle of Stalingrad, or a bombed-out Berlin with the hammer and sickle over the Reichstag than we do, say, a devastated Manila, the “Pearl of the Orient.” Redemption is not just an excellent book, it is a double contribution as an homage to and case for caring about the punishing work of the awesome formations of the Sixth Army under Walter Krueger, the Eighth Army under Eichelberger, the Fifth Air Force, and the independent 503rd Airborne, only to name a few, and ultimately the resistance, subjection, and liberation of the Filipino people themselves.

David Murphy holds a Masters of Finance from the University of Minnesota.