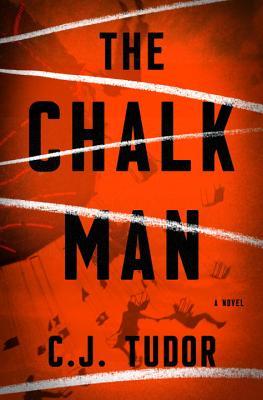

The Chalk Man by C. J. Tudor

/The Chalk Man

by C. J. Tudor

Crown, 2018

CJ. Tudor's debut thriller The Chalk Man arrives bearing not one, not two, but twenty-seven ecstatic blurbs from authors and booksellers and industry organs like Kirkus Reviews and Publishers Weekly and Library Journal, all praising the book as a cleverly-plotted magnificent masterpiece and the author as a brilliant and promising new voice, a revelation and a marvel.

No book can possibly live up to such praise, much less a debut novel, and The Chalk Man dramatically, immediately doesn't. The narrative is split between 1986 and 2016, with the earlier plot-line featuring a young teenager named Eddie and his wacky, foul-mouthed, pop culture-quoting, misfit buddies Mike, Dustin, Lucas, and – or no, that would be the wacky, foul-mouthed, pop culture-quoting misfit young teens in Stranger Things – here Eddie's wacky, foul-mouthed, pop culture-quoting misfit young teen friends are Fat Gav, Metal Mickey, Hoppo, and Nicky, who in 1986 devise a series of chalk figures that forms a secret code known only to them, a kind of cryptology for the private world of their lonely, geeky world. That world is violently interrupted by their albino teacher Mr. Halloran, the so-called “Pale Man” who goes on to haunt their childhoods.

In the 2016 segments, an all-grown-up Eddie receives a letter in the mail containing a chalk man drawing, as do all of his all-grown-up friends. They naturally suspect each other of pulling off an elaborate prank, until the inevitable happens and people start dying, after which the tension between the two parallel plot lines increases, and Tudor does a capable job of releasing her 1986 clues with a timing that resonates in her 2016 chapters. This is a rudimentary, even skeletal thriller – no art, no eloquence, no finesse, no characters, no depth – but readers who are so enamored of the thriller genre itself that they're willing to invest even a skeletal story with lots of imaginative help it shouldn't require might find in these pages some faint echo of the End Times hosannas of praise it's somehow received before publication.

Readers who expect more resolutely won't get it. At its best, Tudor's prose is baldly functional; at its worst – a worst that crops up often enough in this book to warrant some quiet time for its editor – it's stooped under leaden phrasings, boring cliches, and heaps of nonsense-writing. When Eddie reflects on the Pale Man, he thinks:

Even as a kid I could tell that Mr. Halloran was really talented. There's something about pictures done by someone with talent. Anyone can copy something and make it look like the thing they're copying, but it takes something else to bring a scene, to bring people, to life.

As mentioned: nonsense. There's something about pictures done by talented people that shows they're talented – well, yes, one would assume. And “anyone can copy something and make it look like the thing they're copying”? Can you? Can all of your friends? Again: nonsense. And the kind of nonsense that briefly takes the reader out of the story.

That kind of nonsense recurs throughout the book. Another moment from grown-up Eddie:

I plod upstairs, have a quick shower and then change into gray cords and a shirt I deem suitably casual. I drag a comb through my hair. My hair springs back even more roughly. As hair goes, mine has a stubborn resistance to all methods of styling, from the humble comb, to waxes and gels. I've shorn it almost to the bone and it has miraculously gained several unruly inches overnight. Still, at least I have hair. From the photos I've seen of Mickey, he hasn't been so fortunate.

Even overlooking the clunky workshop-phrasings (plodding upstairs, dragging a comb), this throwaway paragraph is riddled with halting problems – not just the inanity of that “as hair goes” (as opposed to what? Shin bones?) but also the fact that humans can't grow several inches of head-hair overnight. It's the kind of amateurish overwriting that's predictable with debut authors – in this case, Tudor wants to stress the trivial fact that the character has thick hair, unruly hair and badly overdoes it – and it should have been tamped down and weeded out by Tudor's editorial team. There's no evidence that this happened, which is alarming. And far more alarming is that the good-natured but shoddy end result has been heaped with such superheated praise. A first-time author who makes these kinds of missteps all throughout her debut and receives nothing but praise for it is extremely likely to write a second book along the same lines as the first, and then maybe create a career along those lines. Here's hoping CJ Tudor is the introspective type.

Steve Donoghue was a founding editor of Open Letters Monthly. His book criticism has appeared in the Boston Globe, the Wall Street Journal, and the American Conservative. He writes regularly for the National, the Washington Post, the Vineyard Gazette, and the Christian Science Monitor. His website is http://www.stevedonoghue.com.