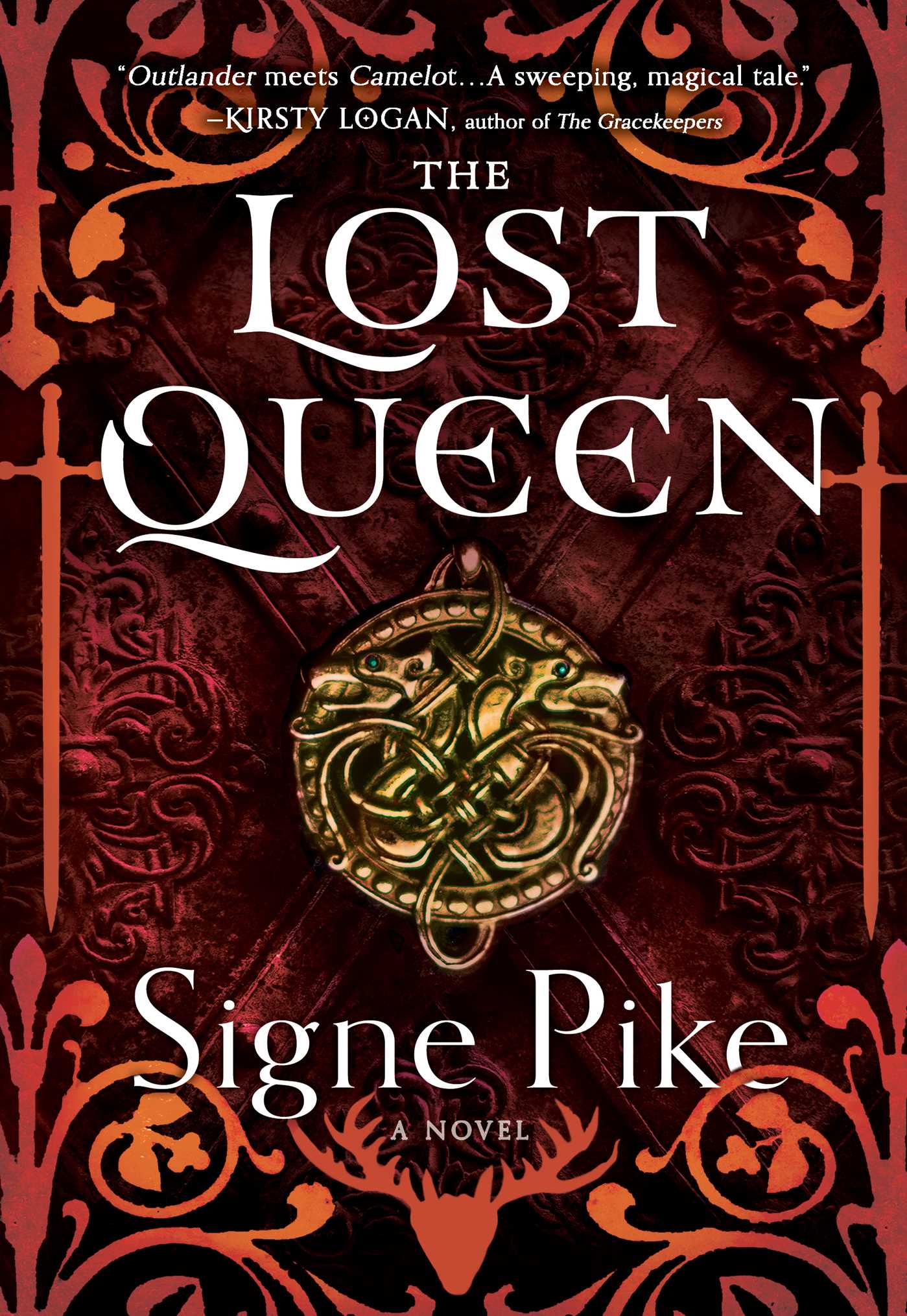

The Lost Queen by Signe Pike

/The Lost Queen

by Signe Pike

Touchstone, 2018

Signe Pike ends her debut novel, The Lost Queen, with an Author’s Note clarifying some of the literary and historical groundwork she did in order to craft this story, the first in a projected trilogy, about Languoreth, a “lost” queen of sixth-century Celtic Scotland. Pike’s excitement about the dramatic potential of this historical footnote is obviously unfeigned and very contagious; Author’s Notes laying out patterns of research can often be tedious anti-climaxes to the books they follow, but in Pike’s case, it’s easy to imagine her giving a lecture on the history and folklore of this period that would fill the seats of a college auditorium.

Even so, this Author’s Note contains a line that’s virtually guaranteed to harrow up thy soul and freeze thy young blood. See if you can spot it:

I couldn’t stop thinking about Languoreth and the epic times she lived through: the battle that tore her family apart, the Anglo-Saxon migrations, and the first ever politico-religious acts of violence that the Britons of Strathclyde would have likely experienced. Moreover, in today’s world, powerful female role models must be brought forth and honored now more than ever. I thought it a travesty that Languoreth had been written out of history, her powerful story never told.

Yes, exactly: what could be more deadly to the very idea of a dramatic novel than the prospect of trudging around in the wake of a role model for 500 pages? (Likewise that bit about ‘in today’s world.’ There are currently over a dozen female leaders of world nations; if Pike thinks this is a lower figure than in 573 - or 1073, or 1573, or 1973 - another trip to the archives might be in order). Role models might be good things in lived reality (although considering some on display in 2018, the jury is still out on that), but they’re lethal to novels.

Fortunately, Pike has the good sense not to have the courage of this particular conviction. Young Languoreth, daughter of the king of Strathclyde, is a wonderful fictional creation, observant but sometimes pigheaded, well-taught in the fine ways of court and kingdom but also a vibrant individual, a heroine but thankfully not a paragon.

This is likewise true of her twin brother Lailoken, a hot-tempered and over-protective young man who will grown (presumably over the course of the trilogy) to become a towering figure, the historical basis for the famous character of Merlin the magician. Despite the presence in The Lost Queen of a character who’ll become known as Uther Pendragon, plus that shadow of the man who will become Merlin, despite the grounding in the mytho-history of early medieval chroniclers like Gildas, and despite obviously advantageous easy comparisons to books like Marion Zimmer Bradley’s The Mists of Avalon, Pike has crafted a world of her own in these pages, a rough association of ragged, rural little kingdoms facing the looming threat of foreign invasion and the more insidious social undercurrent represented by the Christian monks steadily infiltrating their lands and creating a resistance to the Old Ways that features prominently in this first book (there’s a genuinely creepy scene in which Languoreth is confronted by a silent menacing monk while deep in a forest) and will likely only grow in significance as the series progresses.

In addition to the broad cast of well-drawn characters, the book also has many quick, fine descriptions of the lush natural settings against which the stark danger of the plots unfolds. And almost all such descriptions, there’s a nod to time, to the fact that although Languoreth’s era is fifteen hundred years in the past, it contains many reminders of time stretching even further back, as in the seemingly offhand mention of the barrows that dot the land:

The road to Patrick was a muddy ribbon that wound west, high above the Avon Water as it passed between towering oaks and shady pine forests. Alder, ash, and birch found light closer to the pastures as we turned north, where the trees gave way to fields and open wind. In the distance the pastures rose with mounds of my father’s ancestors, the sleeping dead. We joined the main road and looked out over the great river Clyde, where flat-bottomed boats floated downriver toward the capital carrying stout barrels of ale and swaths of timber for the shipyards of Patrick or for Clyde Rock, the fortress of the high king at the mouth of the two rivers.

The Lost Queen arrives in a beautifully-produced edition from Touchstone and Simon & Schuster, a think of heavy, ornate design that matches the dramatic and sometimes overheated indulgences of Pike’s narrative and dialogue. Although the pacing never slows below a brisk canter, there are many elements of this story that are pleasingly old-fashioned in their primary-color urgency. The Lost Queen will also draw inevitable comparisons with Diana Gabaldon’s Outlander, and fans of that series will find something of its earnest melodrama here, as well as a considerably more elusive quality: the feeling of a very promising start.

Steve Donoghue was a founding editor of Open Letters Monthly. His book criticism has appeared in the Boston Globe, the Wall Street Journal, and the American Conservative. He writes regularly for the National, the Washington Post, the Vineyard Gazette, and the Christian Science Monitor. His website is http://www.stevedonoghue.com.