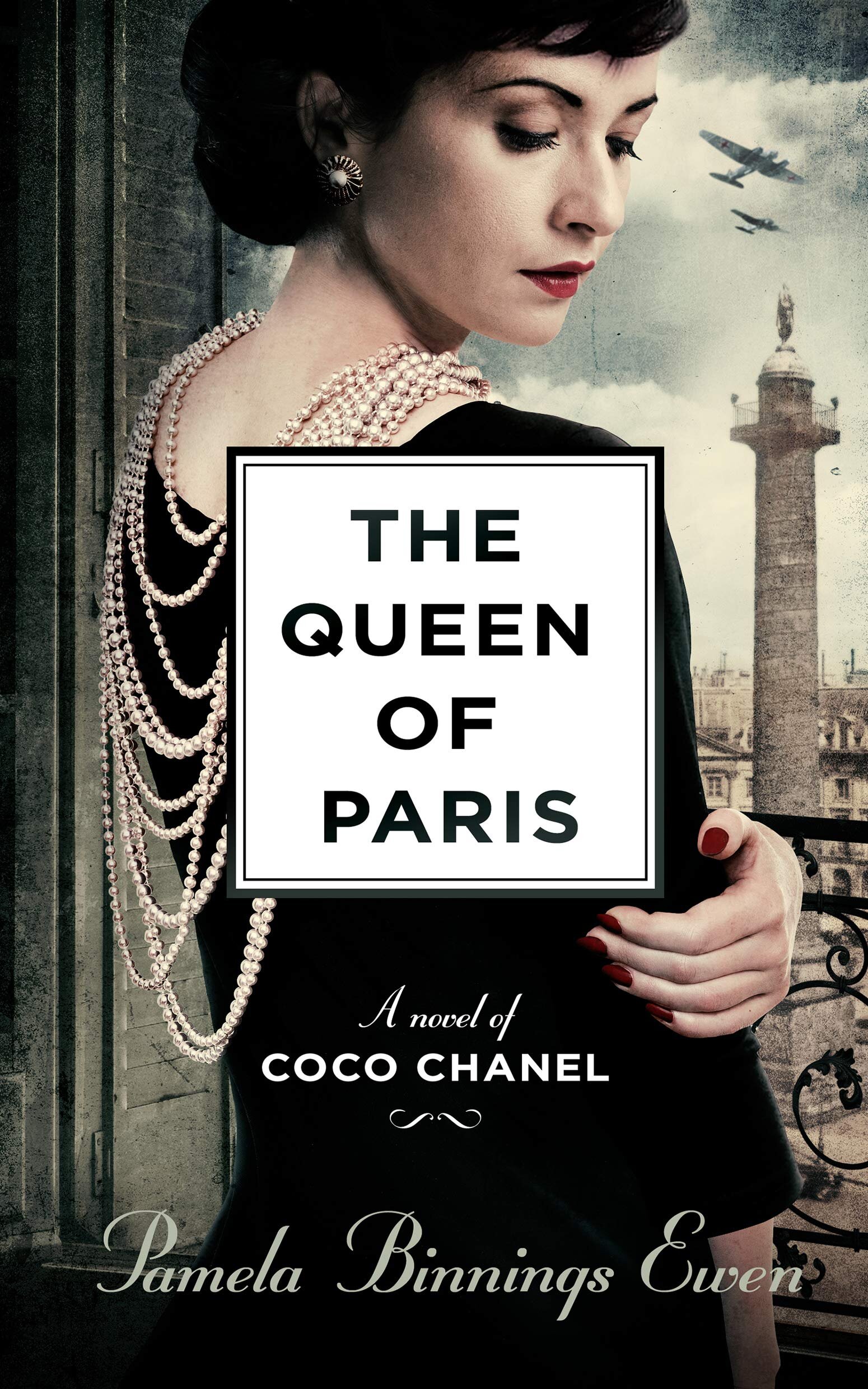

The Queen of Paris by Pamela Binnings Ewen

/The Queen of Paris

By Pamela Binnings Ewen

Blackstone Publishing, 2020

Historical novelists who decide to write about monsters have two choices: defense or prosecution. They can either craft a novel designed to convince readers that the monster was misunderstood rather than evil, or they can dramatize the evil so readers can revel in the chills. The latter gives you, for instance, Patrick Suskind’s Perfume; the former gives you Hilary Mantel’s Thomas Cromwell novels.

Moderate-minded readers may argue that the truth is always somewhere in the middle, and this is certainly true - except for monsters. Monsters live at the extremes of every spectrum. They’re the only ones who can. That’s what makes them monsters.

The famous fashion icon Coco Chanel was a monster. She was petty, vindictive, and viciously antiSemitic, and because she combined all three of those things with an unsleeping personal hunger for decadence and advancement, she was in perfect moral alignment with the Nazis when they invaded Paris.

In Pamela Binnings Ewen’s experienced hands, this monstrous Coco Chanel comes alive in the pages of The Queen of Paris (a very attractively designed new hardcover from Blackstone Publishing) as thoroughly as she ever did in even a brilliant biography like that by Edmonde Charles-Roux. Ewen is a prodigious researcher but has two outstanding gifts not usually given to such researchers: she never simply dumps her exposition onto the page, and she isn’t afraid to do a little discreet violence to the facts for the benefit of her fiction.

The result is a fictional portrait of Coco Chanel so oily and convincing that she’ll linger in the reader’s mind long after they finish the book. Chanel’s business maneuverings are dramatized in their byzantine complexity, and her increasingly chummy dealings with the new overlords of Paris - including her willing participation in espionage on behalf of the Nazis - are rendered with a convincing combination of fulsome prose and fairly knowing innuendo, all done in a supple present tense.

Ewen walks a fine line between humanizing her main character and empathizing with her. When the inevitable subject of Paris Jews comes up, for instance, readers are very nearly tempted to miss how cold a job Ewen is doing:

“And this French problem includes your Jews, of course. Doesn’t it?”Another slight change of tone warns this is not a casual question. In fact, she realizes, this is a test.

There are Jews she likes very well, and others - fingering the pearls around her neck and thinking of the shopkeeper in Limoges years ago who gave Papa only ten francs for Maman’s pearls - she despises.

Other scenes crowd the distinction a bit more than is strictly believable; there’s a strong impression that even Ewen’s strong stomach for her star occasionally weakened, that she perhaps occasionally found herself wanting to write about somebody who didn’t so frequently make her skin crawl. Take this moment, for example:

She hurries to the grand entrance hall and the concierge desk, but the expression on Géraud’s face freezes her. Following his eyes, she turns, looking through the front entrance door where the boys outside are fighting with the guards - she counts them, there are three - and a guard jams the butt of a rifle against one’s head, knocking the fellow to the ground, so now there are only two and they’re running off, heading off across the open plaza. The fools, the little fools! And then her heart pounds as two of the guards take a knee and raise their rifles, sighting the running boys. Without thinking, Coco moves toward the door, her arms outstretched, reaching. Two hands grab her from behind, stopping her. She turns, meeting the eyes of a young Wehrmacht officer. He shakes her head. “They were attempting to enter.” he says.

Anyone who’s read any of those aforementioned Chanel biographies will chuckle a little at that “her arms outstretched,” but if we all want more big, delectable historical novels from Pamela Binnings Ewen, we should probably cut her some slack.

—Steve Donoghue is a founding editor of Open Letters Monthly. His book criticism has appeared in The Boston Globe, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, and The American Conservative. He writes regularly for The National, The Vineyard Gazette, and The Christian Science Monitor. His website is http://www.stevedonoghue.com.