The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway

/The Sun Also Rises

By Ernest Hemingway

Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition, 2022

There are two main boons attending the lapsing of Ernest Hemingway’s debut novel The Sun Also Rises into the public domain in 2022. The first is that it’ll occasion a veritable flood of new editions of the book: new hardcovers, deluxe illustrated or annotated editions, the kinds of mass market paperbacks it hasn’t seen in thirty or forty years, and so on. And the second is that almost every one of those new editions will be accompanied by thought-provoking new essays on the book.

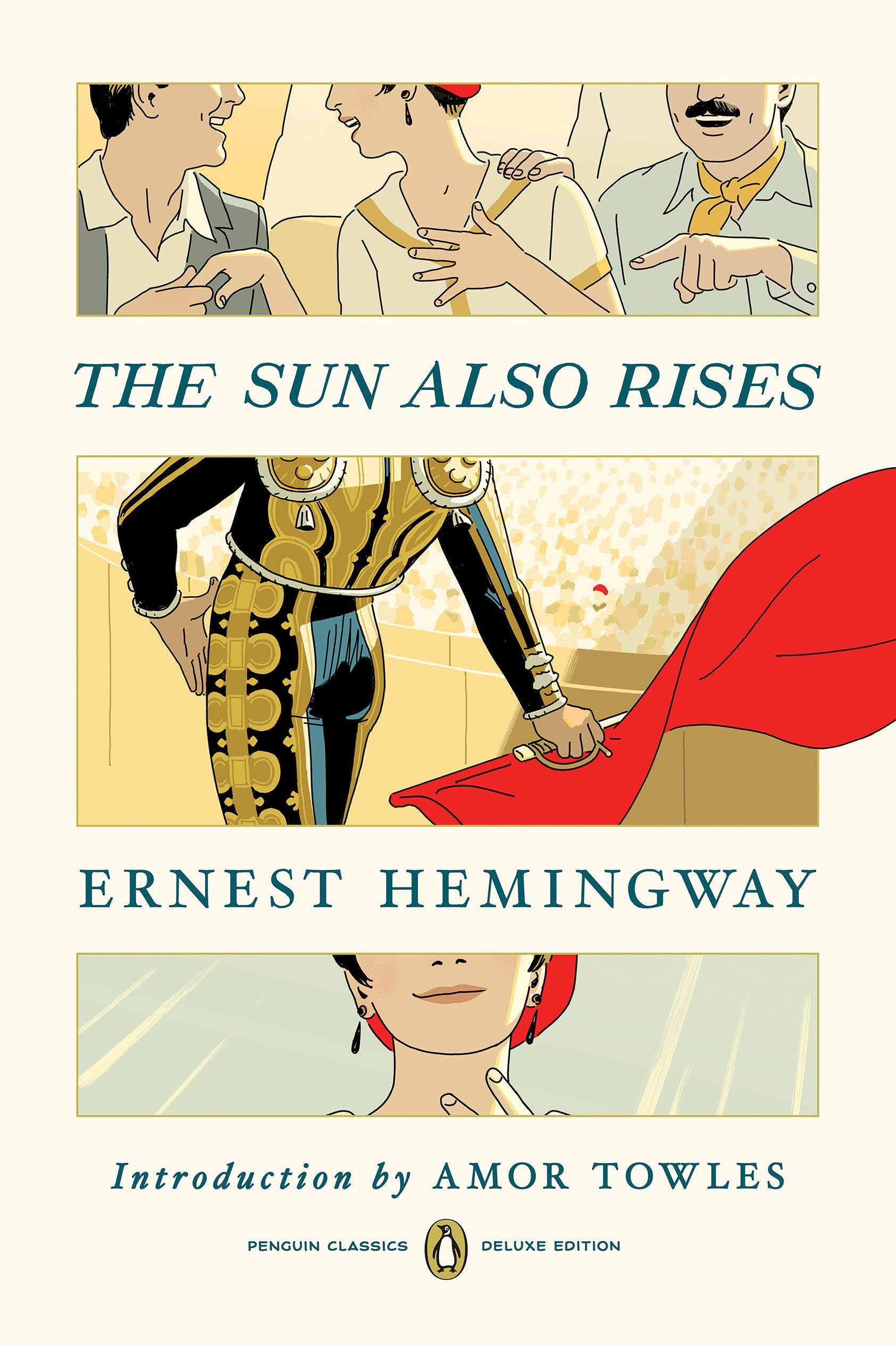

In the new Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition of The Sun Also Rises, readers get one of those two. The book itself is a lovely trade paperback with deckled edges and French flaps, a joy in the hand, with artwork by Kikuo Johnson on every surface: men and women talking, drinking, kissing, the allure of a woman’s throat, and, of course, the bright red flare of the matador’s muleta. The Penguin Classics Deluxe volumes are always visually outstanding, and this latest one is a fine addition to the line.

The edition includes an Introduction by bestselling novelist Amor Towles, and it’s oddly statistical, like finding a new edition of The Custom of the Country with a Preface by Bill James where he industriously totes up the hansom fares. “If we compare The Sun Also Rises to three important novels published in 1925 – F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, and Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy – we find that Hemingway is using sentences that are half the length of his peers’, averaging fewer than ten words versus about twenty.” “Jake makes eight stops at which he drinks nine kinds of alcohol …” “In the course of the novel, Jake crosses seven different bridges …” and so on. You start to feel like you need an abacus.

Towles does make an excellent point in the midst of all this bookkeeping, one that readers, especially readers encountering the book for the first time, are well-served to remember: when he wrote this book, Hemingway “had yet to experience the potentially compromising effects of fame, wealth, and recognition.” The tanned, brawny young man carousing with his friends and lovers in the Latin Quarter in 1926 had had good (although not good enough for him) notices for his short stories, but he had not yet fully created the Hemingway theater. He knew that a lot was riding on this novel.

His agent thought the book was elaborately alive. His mother thought it was a filthy book (and that her son was probably in need of more church-time). Fitzgerald thought it was strong but suffered from excessive throat-clearing (Hemingway cut out a chunk of the beginning at his suggestion). And the reaction of Hemingway’s friends – whose stories, personalities, and even diction he meticulously quarried for the book – ranged from tolerant bemusement (“I’m not that bad, am I?”) to outraged pain (Harold Loeb, the object of Hemingway’s bitter antisemitism in real life and the model for Robert Cohn, the object of the book’s bitter antisemitism, was physically sickened by the betrayal of his portrayal). And virtually everybody who read the book recognized on some level that they were looking at an index item, a thing that would be a reference point for a generation and even a movement.

And maybe there’s a third boon to new editions like this one: they’re all invitations to experience that literary bombshell straight-on. Once Towles finishes counting the silverware, that is.

Steve Donoghue is a founding editor of Open Letters Monthly. His book criticism has appeared in The Washington Post, The American Conservative, The Spectator, The Wall Street Journal, The National, and the Daily Star. He writes regularly for The Boston Globe, the Vineyard Gazette, and the Christian Science Monitor. He’s a books columnist for the Bedford Times Press and the Books editor of Big Canoe News in Georgia, and his website is http://www.stevedonoghue.com.