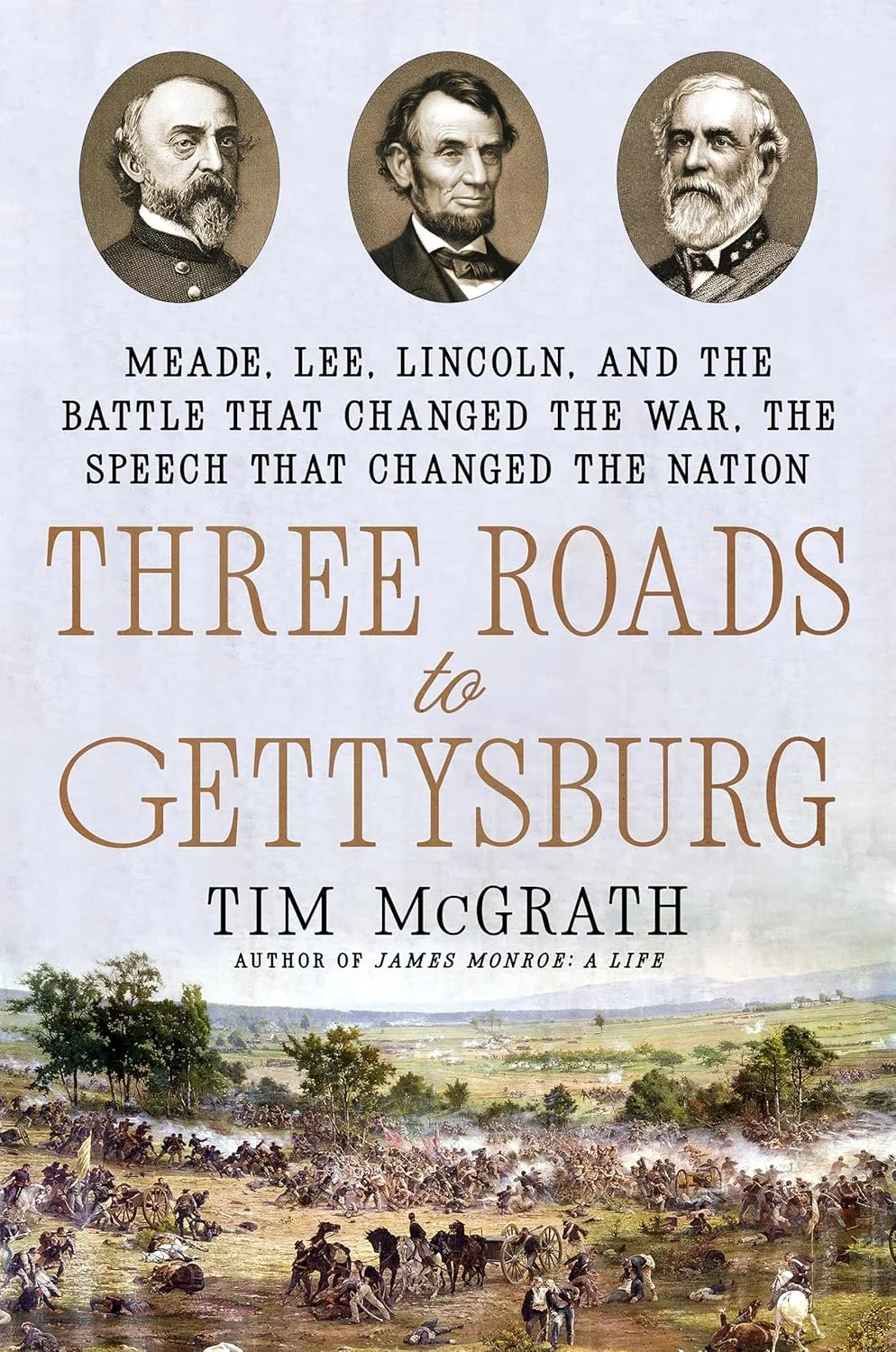

Three Roads to Gettysburg by Tim McGrath

/Three Roads to Gettysburg: Meade, Lee, Lincoln, and the Battle That Changed the War, the Speech That Changed the Nation

By Tim McGrath

Caliber 2025

Tim McGrath’s new book Three Roads to Gettysburg (with its long and ungrammatical subtitle) takes its time getting to the boiling cauldron that is obviously its point and focus, the Battle of Gettysburg itself, which in 1863 saw the shattering of a Confederate advance into Pennsylvania after three days of increasingly ferocious fighting. Confederate General Robert E. Lee came to Gettysburg a nearly legendary figure, having led his troops to a string of improbable victories against much greater armies led by much lesser men. Facing him at Gettysburg was George Gordon Meade, an experienced soldier who’d already been wounded while fighting against Lee but who’d only been in command of the Army of the Potomac for a few days before he led that army to Gettysburg. And eagerly awaiting news of battle was US President Abraham Lincoln back in Washington, hoping Meade could avoid the disaster of a Southern victory on Norther soil.

Before he gives readers the battle, which is here rendered in 80 tense and gripping pages at the book’s climax, McGrath first gives them the men, their youths and varying upbringings, with Lincoln being the son of the rough-and-tumble prairie, Meade coming from the rapidly-industrializing north, and Lee being a Southern slave owner who bravely fought for his country right up until the moment when he decided to betray it. By the time he has the destinies of these three men intersect at Gettysburg, McGrath has thoroughly and very effectively introduced them to his readers.

He clearly knows the main obstacle to such an approach: nobody’s interested in Meade. Thanks to the spasm of nostalgia-driven racism/racism-driven nostalgia that gripped the country in the postwar generation, Lee is a familiar name in the US, and of course Lincoln will never need an introduction. But Meade? Philadelphia, West Point, a life-long professional soldier"? His own slim claim to posterity is that he was in command of the Union forces at Gettysburg.

And that claim itself is contested, or at least troubled. After the third day of the fighting, when Lee’s idiotic massed frontal assault on elevated artillery ended in disaster, Meade allowed his decimated forces to withdraw out of Pennsylvania instead of pouncing to annihilate them, capture Lee, and very likely end the war. He was subsequently attacked for this and other failings, most viciously by a pseudonymous “Historicus” in the New York Herald, and he chaffed at not being able to mount an effective defense of his own record. “Nine years earlier, Meade had taken command of an army yet to win a decisive battle against an opponent who had never lost one,” McGrath writes. “Since then, not only his generalship had been called into question but also his integrity, the result of which cast him into the shadow of history.”

As McGrath notes, five months before his death in 1872, the dour Meade complained to his wife, “I suppose after awhile [sic] it will be discovered that I was not at Gettysburg at all.”

In a way, the main strength of Three Roads to Gettysburg is that the Meade road doesn’t feel like a dead end; McGrath makes him just as interesting as his much more famous co-stars. This is always the danger of the old narrative numerology gimmick, seen just as clearly in Three Roads to the Alamo by William Davis, where readers naturally interested in Jim Bowie and especially Davy Crockett must eat their vegetables and learn a lot about William Travis (the numerology is also necessarily exclusive: just as Santa Anna doesn’t get a road named after him in the Davis book, so too poor neurotic Jefferson Davis back in Richmond has no street signage in McGrath’s book). The emphases highlight the artificiality, but let’s be honest here: only the most hopeless American Civil War addicts would buy a biography of George Meade.

But there’s plenty of allure for readers of this account of when, as McGrath puts it, “The gods of war had won over the better angels of America’s nature.” Lee has had his thousands of books and Lincoln his tens of thousands, but nevertheless they’re both well-served here. And sour-faced old Meade, with his long-suffering wife and his adoring brood of children and his faithful horse Old Baldy and his flinty bravery, well, his ghost will have to be satisfied with what amounts to a mighty fine memorial.

Steve Donoghue is a founding editor of Open Letters Monthly. His book criticism has appeared in The Washington Post, The American Conservative, The Spectator, The Wall Street Journal, The National, and the Daily Star. He has written regularly for The Boston Globe, the Vineyard Gazette, and the Christian Science Monitor and is the Books editor of Georgia’s Big Canoe News