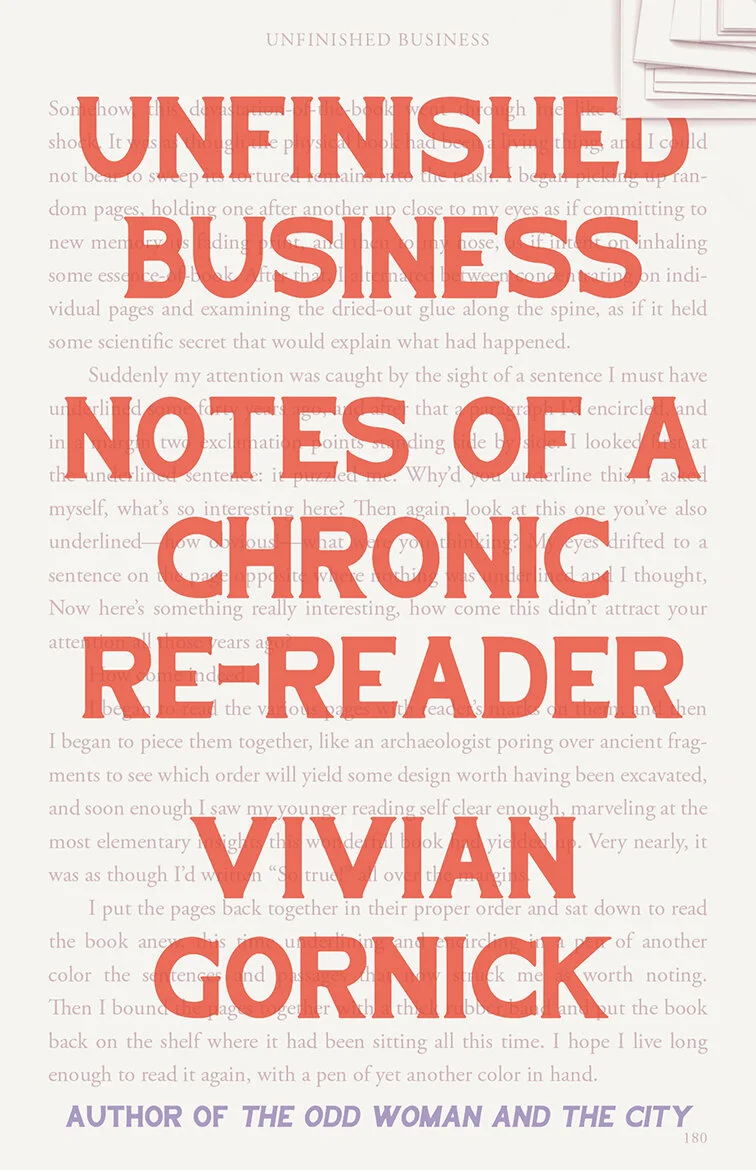

Unfinished Business by Vivian Gornick

/Unfinished Business: Notes of a Chronic Re-Reader

By Vivian Gornick

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020

“It has often been my experience that re-reading a book that was important to me at earlier times in my life is something like lying on the analyst’s couch.” So begins the critic Vivian Gornick’s Unfinished Business: Notes of a Chronic Re-Reader, an elegant memoir of a long lifetime of reading. Growing up, she knew that meaningful books showed her a “courage for life” and a kind of “companionateness,” the combination of which gave her both peace and excitement. As she re-reads these books, she begins to recognize that often when she picks up an old favorite, “the narrative I have had in my heart for years is suddenly being called into alarming question.” Gornick realizes that her ideas about books shift and change as she herself shifts and changes. Unfinished Business is her attempt to trace that process through a handful of books that have meant a great deal to her over the years, from D. H. Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers to the prose of Elizabeth Bowen, from Colette’s work to that of Doris Lessing.

Gornick’s experiences of reengaging with favorite books are often shaped by her feminism. She realizes that her experiences—from sexual exploration to relationships, from her childhood to her career—are not just personal but also political. That understanding underlines much of the close reading and analysis of the texts she finds herself reading and re-reading. When she was young, Gornick’s initial understanding of feminism led her to believe that a life oriented around sexual passion was a life-supporting liberation. Over time, the idea of sexual love as a kind of freedom begins to seem to her like mere illusion. She comes to believe that people often use “desire to avoid rather than to illuminate.” Neither sexuality nor romantic relationship lies at the heart of any human’s core identity, she argues. In response to that realization, Gornick begins to search instead for narratives, for example, that cast women at the heart of the story instead of making them mere foils to male protagonists. She is also interested by texts that consider how men choose, or fail to choose, actions that move their own narratives forward.

One of Gornick’s most thoughtful essays in the book explores her changing interpretations of J. L. Carr’s A Month in the Country. In the forward to his short novel, Carr states that he initially intended to write a “rural idyll” about an event in his life. As he wrote, however, a “darker landscape” emerged, of Britain struggling with the aftermath of the First World War. When Gornick first read Carr’s quiet book, she embraced the idea of a young soldier making a fresh start after he returned from war. When she picks the book up years later, she is struck by the main character’s desire to not “be a casualty anymore.” He has found what he hoped would be a path to healing from the shocks of battle, but the peace he sometimes experiences at his work does not lead to human connection or purpose. The book ends not with a clean slate but with, as Gornick writes, “melancholy thick enough to cut with a knife.” The trauma of war has utterly stunted the spiritual growth of the novel’s main character. That is, pain has stunted his ability to act. Gornick understands this fact only when she begins to conceive of a more nuanced meaning of liberation.

In the lovely final chapter, Gornick recounts the experience of coming across a long-unread mass-market paperback on her shelves, a book published in the 1970s. When she picks it up, the volume immediately begins to fall apart in her hands. She starts to reassemble the loose pages “lying all about, on my lap, on the desk, on the floor,” and is puzzled when she catches “sight of a sentence I must have underlined some forty years ago, and after that a paragraph I’d encircled, and in a margin two exclamation points standing side by side.” She considers the sentences: “Why’d you underline this, I asked myself, what’s so interesting here? Then again, look at this one you’ve also underlined—how obvious!—what were you thinking?” When she glances at the next page, she is struck by an insight printed there, yet with none of her markings. She thinks to herself, “Now here’s something really interesting, how come this didn’t attract your attention?” So, she begins to read anew, “underlining and encircling in a pen of another color the sentences and passages that now struck me as worth noting.” After she finishes, Gornick places the pages away, carefully bound together now to await another rereading—a re-reading she will do “with a pen of yet another color in hand.” Her new understandings will join the old on the pages of the books on her shelves, creating proof that each text always remains alive to the attentive re-reader. Reading a book, in other words, is always an unfinished business.

—Hannah Joyner is an independent scholar living in Washington, D.C. Her work includes Unspeakable: The Story of Junius Wilson and From Pity to Pride: Growing Up Deaf in the Old South. You can find her on BookTube at https://www.youtube.com/c/HannahsBooks.