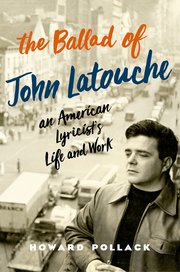

Unsung Hero: Reviving the Forgotten Career of a Theatrical Genius

/The Ballad of John Latouche: An American Lyricist’s Life and Work

by Howard Pollack

Oxford University Press, 2017

When the lifeless body of John Latouche was discovered in his Vermont home by a friend on an August morning in 1956, it was assumed he was asleep. He had shown no signs of a major illness beyond severe chest pains, he had waved away suggestions that a doctor be called, and treated his symptoms with a bicarbonate of soda. But as an autopsy later confirmed, Latouche had suffered a coronary occlusion before dawn that morning. He was 41.

His death stunned the New York literary world, whose population knew him as not only a superbly talented musical theater lyricist, one who brought a rare sophistication and poetic sensibility to his work, but also as a social whirlwind who could be astonishingly charming and (particularly to his collaborators) exasperatingly capricious and erratic. He was promiscuous with both men and women—but mostly men. He drank heavily, smoked incessantly, and encouraged his considerable creativity with prescription medications. The novelist Dawn Powell, a friend who worked with him on a 1940 musical, wrote about his death in her diary: “Incredible that this dynamo should unwind, but I think I can guess how. Talentless but shrewd users pursued him always—he was driven: harnesses and bridles and wagons were always being rushed up to him to use this endless gold.” Benzedrine, Miltown, Nembutal, and Dexedrine severely confused his body and added to the inevitability of his death.

Other luminaries weighed in with tributes, including close friends Frank O’Hara, who dedicated a poem to him, and Carson McCullers, who sent a written eulogy to be read aloud at the funeral: “John had humanity and gaiety, there was in him a sense of communication I have known with no other.” Latouche’s reputation among his peers was based on nearly 20 years of writing, not only song lyrics, but poetry, film and radio scripts, short stories, and translations (Verlaine and Brecht, among others); he created his own independent film company, and even found time for naval duty during World War II. All this, as well as a period of blacklisting during the Red Scare.

Today, he is remembered, if at all, for a handful of impressive musical theatre projects which for enthusiasts like me have always been tantalizingly out of reach—most are unrevivable for any number of reasons. His early 1940 score for Cabin in the Sky is rich in melody and wit, but its take on a “Negro” folk tale, while earnest and charming, is often condescending and borderline racist—not surprising, when nearly all of its collaborators were white. The same problem continues to plague Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, written in 1935, and still mired in controversy whenever it’s mounted.

The Golden Apple, a musicalized Odyssey, won plaudits and awards in 1953, but mistakenly took its sterling off-Broadway credits to a larger space on Broadway and—caviar to the general—could eke out only a few months there. It has yet to be revived on Broadway, and its occasional concert stagings have revealed bountiful pleasures, as well as irritating limitations.

In these projects—and many more, including flop Broadway musicals like The Vamp, The Lady Comes Across, Beggar’s Holiday (with music by Duke Ellington), and more—Latouche’s work was often judged a flower among weeds. He left no enduring classic household-name show in his portfolio, no Oklahoma!, no My Fair Lady, no Guys and Dolls. But as Howard Pollack demonstrates, in his exhaustive and most welcome biography, The Ballad of John Latouche: An American Lyricist’s Life and Work, he was one of the most prodigiously talented practitioners of his craft, frequently the equal of those whose work has been celebrated with luxe coffee table treatments: Oscar Hammerstein, Lorenz Hart, Stephen Sondheim, Ira Gershwin, Johnny Mercer.

John Treville Latouche was born in Baltimore and raised in Richmond, Virginia. An early interest in music and the theater helped alleviate the “terrors” he experienced—“hardly surprising,” Pollack writes, “given the poverty, rootlessness, abuse, alcoholism, and psychosis that plagued his family.” Such travails led Treville (as he was known most of his early life) to leave Virginia for New York City, where he eventually enrolled in Columbia (and later dropped out). There he began winning minor writing awards for his poetry and prose. Contributions to collegiate variety shows revealed a skill for song lyrics, although for the rest of his life he aspired to be known as a serious poet. That volume never appeared.

Somewhere along the way, “Treville” made way for the less pretentious “John,” so it was “John” for his byline, but “Touche” to most of his friends. He earned money early on by writing bawdy songs for cabaret singers (“I want to end up with my end up in Harlem”) and other freelance projects. His first taste of national exposure came with a commission from the Federal Theatre Project to contribute a song for a musical production, Sing For Your Supper. With composer Earl Robinson, Latouche created “Ballad For Americans,” an energetic 10-minute “folk opera cantata” (not as dreary as it might sound) that extolled the virtues of democracy and liberty through the voice of an Everyman figure. Performed at conventions of both the Republican Party and the American Communist Party, “Ballad” was promptly recorded by artists as disparate as the great African-American baritone Paul Robeson and Bing Crosby, the most popular singer of his day. Its sentiments seem naïve and bloated today, but they provided just the pep talk the country needed during those unsettled times as the it crawled out of a depression and moved inexorably to war.

“Ballad” is peopled by a chorus trying to seek the identity of a passing stranger who offers a folksy history lesson that reminds them of the country’s bumpy past and resilient future. “Who are you?” the chorus keeps demanding, but the traveler remains elusive:

“Well, I'm an Engineer, musician, street cleaner, carpenter, teacher. How about a farmer? Also. Office clerk? Yes sir! That's right. Certainly! Factory worker? You said it. Yes ma'am. Absotively! Posotutely! Truck driver? Definitely! Miner, seamstress, ditchdigger, all of them. I am the ‘etceteras’ and the ‘and so forths’ that do the work.”

Chorus: “Now hold on here, what are you trying to give us? Are you an American?”

Man: “Am I an American? I'm just an Irish, Jewish, Italian, French and English, Spanish, Russian, Chinese, Polish, Scotch, Hungarian, Swedish, Finnish, Greek and Turk and Czech.”

At the climax, as the music swells, he solves the mystery of his identity:

“And now you know who I am.

America! America!”

Not everyone was a fan. James Agee dubbed it “inconceivably snobbish, aesthetically execrable” and another critic felt it a propagandistic celebration of American exceptionalism.” Hmmm. Plus ça change. But despite its critics, the recording sold in the tens of thousands.

Hard on “Ballad”’s heels came Cabin in the Sky, with composer Vernon Duke, born Vladimir Dukelsky near Pskov, Russia. As Dukelsky, he had a significant career as a classical composer; as Duke, he wrote popular songs, among them the beautiful “April in Paris,” “I Can’t Get Started,” and “Autumn in New York.” He was a superb melodist but had the world’s lousiest luck in choosing the shows worthy of his talents. For nearly 30 years, Broadway show after show he helped create went under after a brief life—for various reasons, usually not of his making—and for some of them he took Latouche down with him.

But Cabin in the Sky was the exception—not a financial success, but fondly remembered mostly remembered for its loving film adaptation, directed by Vincente Minnelli in 1943, and blessed with a jazzy, high-stepping score that included what would become Latouche’s best-known song. It was added late in rehearsals to accommodate the abundant gifts of its leading lady, Ethel Waters, one of that century’s greatest performers. She played Petunia, a poor Southern housewife, so desperately in love with her gambling, philandering husband that she takes on the Devil himself to save his soul. When Joe dies early on, but is given a reprieve by an angel, Petunia exults in his recovery and declares her readiness to risk her heart all over again.

“Here I go again

I hear those trumpets blow again!

All aglow again,

Takin’ a chance on love!”

And with this, Duke and Latouche created one of the most enduring classics in the canon of the American Popular Song. A showstopper since its first performance, it has been recorded countless times, but none so memorably as originally performed. Impossible to say what makes a song endure, but in this instance it helps to have an irresistibly jaunty melody, and a lyric artfully simple, clever, and universal (who doesn’t feel that falling in love is a delicious gamble?). Latouche exults in his clean triple rhymes: go again/blow again/aglow again in each chorus, stressing that Petunia has been in love before and knows all the risks—but who can resist the thrill? Peppered throughout are clichés of good luck and gambling:

“I walk around with a horseshoe

In clover I lie

And Brother Rabbit, of course you

Better kiss your foot goodbye!”

“Horseshoe/course you” is charming, but for me nothing in the song beats this triple play:

“This game I’m takin’ a crack at

Sure needs good luck with me

And so I’m takin’ a crack at

Every black cat that I see”

Inspired.

The MGM version unnecessarily adds two other performers to the mix, but nothing can eclipse Waters’ star power:

The years following Cabin, until his death 16 years later, were a roller coaster for Latouche. Two musicals with Duke: Banjo Eyes, for the huge star Eddie Cantor (one of the last to inflict the practice of blackface on a willing audience) and The Lady Comes Across (co-written with Dawn Powell). Both closed in financial tatters. In 1946 came Ballet Ballads, an ambitious mix of music, dance, and opera. His musical collaborator was classical composer Jerome Moross, later known for many fine film scores. Drawing on American folklore (Davy Crockett) and the Bible (Susannah and the Elders) for its component parts, Ballet Ballads has largely disappeared, despite many positive critical responses, particularly for the songs. Once again, it seems to have been too rich or too progressive for the taste of the average theatergoer. For the section called “Willie the Weeper,” the eponymous chimney-sweeper character imagines himself in various guises and attitudes while under the influence of “magical weed.” “Rich Willie” gave rise to this jagged Latouche lyric:

“But how he loved the wonderful weed—

A puff is enough and your mind is freed

From the steel and the stone, the nickel telephone,

The chippies and the sharpies and the two-bit harpies,

The chiselers and the spasms and the store-bought spasms

When the jim jams, the flim flams

The old razzle dazzle has worn you to a frazzle

The forgetful weed

Will get for everyone the kinda fun

They need.”

Tough stuff for the pop culture of 1948.

Despite the commercial failure of Ballet Ballads (and the rather stormy collaboration between musician and lyricist), Latouche and Moross continued their partnership—a happy decision for the American musical. The Golden Apple was not only a masterpiece for both of them, it considered by some to be the finest set of lyrics written for the genre.

Working with a contribution from the Guggenheim folks, the duo concocted a version of the Odyssey set in the Washington State town of Angel’s Roost in 1900. (Latouche often drew upon American folklore and the classics for inspiration; here he combined the two.) Ulysses was a soldier returning home from the Spanish-America War, Penelope, of course his patient wife; Helen was a farmer’s daughter of dirty joke fame, and Paris a traveling salesman.

Moross and Latouche poured their considerable gifts into the musical, creating folk songs, patter songs, ballads, arias, choral numbers and—as in classical opera—the entire show is through-sung, with lengthy passages of musical dialogue pushing the narrative forward. The pair did wondrously well with ballads. “It’s the Going Home Together,” a duet for Penelope and Ulysses, limns the joys of domestic togetherness:

“It’s the coming home together

When your work is through

Someone asks you How de do

And how’d it go today?

It’s the knowing someone’s there

When you climb up the stair

Who always seems to know

All the things you’re gonna say.

It’s the going home together

Through the changing years

It’s the talk about the weather

And the laughter and the tears

It’s the love the you that’s me

And the me that’s you

It’s the going home together

All life through.”

And this, from a disillusioned Penelope, as Ulysses leaves her, in “Wildflowers,” as she laments the gradual dissolution of love, from its early tenderness—

“He brought me wildflowers that grow among the rocks

And picked me wild berries bitter to the tongue

He taught me to tell time by the dandelion clocks

When we were young.

He caught me a mockingbird and wove a willow cage

A cage from the willow where we kissed and clung

He fought me fierce dragons. We were princess and a page

When we were young.”

—to its erosion:

“The berries and the flowers and the dandelions fade

The songbird is silent, shivering in the cold

The dragons come creeping and they tell me I’m afraid

That I’ll grow old.

And I lie in the house

As the stars grow dim

And I think of how his body was

So warm and slim

And I know there ain’t no growing old

For me and for him

No, never, never

Not for me and him.”

Helen (Kaye Ballard) invites Paris (Jonathan Lucas) to share a lazy afternoon (original production)

The Golden Apple also produced another Songbook classic for Latouche, nearly as popular as “Takin’ a Chance on Love.” Sung by Helen to Paris, it’s a sensuous, sly invitation to sex, and an al fresco romp at that. (And note his continued fondness for triple rhymes):

“It’s a lazy afternoon

And the beetle bugs are zoomin’

And the tulip trees are bloomin’

And there’s not another human

In view

But us too.

A fat pink cloud hangs over the hill

Unfolding like a rose

If you hold my hand

And sit real still

You can hear the grass as it grows.

It’s a lazy afternoon

And I know a place that’s quiet

‘Cept for daisies running riot

And there’s no one passing by it

To see

Come spend this lazy afternoon with me.”

The song has been a favorite of jazz and pop singers for more than six decades.

Yet despite critical huzzahs, and a New York Critics’ Award as Best Musical of its season (the first off-Broadway musical to be so honored), Golden Apple could only eke out 125 performances when it moved from its tiny off-Broadway house to a much larger space uptown. Latouche and Moross never collaborated again.

For a time, Latouche threw himself into the maelstrom that was Leonard Bernstein’s and Lillian Hellman’s musicalization of Candide, working as the project’s sole lyricist. Pollack does an admirable job of trying to untangle the fine mess that was the show’s progress from inspiration to fruition, but the bottom line for Latouche: His work was scuttled somewhere in the process in favor of the lyrics of poet Richard Wilbur. Latouche’s contributions are fragmented here and there in the final score, and he received program credit, and presumably royalties. (Not that financial compensation did him much good. Candide opened a few months after his death. Dawn Powell tartly observed that his demise might have been a “desperate, hysterical escape” from Hellman and others involved in the enterprise.)

Happily, one of his works remains intact, and though deemed (again) too risqué for the masses, it has been reinstated in many of the productions that have followed in the five decades since its New York debut. First titled “The Syphilis Song,” then changed to “Ring Around Rosy,” the song is one of Latouche’s wittiest. The character Pangloss—teacher, philosopher, eternal optimist, who pops in and out of the musical in various guises—is sanguine about his disease, and turns its origins (starting with the maid Paquette) into a jaunty patter song:

Oh my darling Paquette!

She is haunting me yet

With a dear souvenir

I shall never forget!

‘Twas a gift that she got

From a seafaring Scot

He received

(He believed)

In Shallot.

In Shalott, from his dame

Who was it certain it came

With a kiss

From a Swiss

(She’s forgotten his name).

But he told her that he

Had been given it free

By a sweet little cheat

In Paree.

It would be difficult to assess which of Latouche’s best work is his least familiar with the general public, but The Ballad of Baby Doe might hold pride of place. It’s that rara avis, an American opera that has found some measure of success. Based on the historic figure, Horace Tabor, a wealthy prospector-turned-politician, and his young mistress, the opera had its premier in Colorado in 1956, several weeks before Latouche’s death. In the 60 years since then, it has become part of the standard repertory in some venues (including New York’s City Opera), although never performed at many of the major houses such as the Metropolitan. Its hoped-for transfer to Broadway failed en route. Critics have long been divided about its quality, and when praise was accorded, the healthy share went its composer, Douglas Moore. Opera librettists are almost always ignored; it is Verdi’s Rigoletto we know, not Verdi’s and Francesco Maria Piave’s. This is a sad oversight in the case of Baby Doe, whose lyrics often demonstrate Latouche at his delicate, exquisite best. The great soprano Beverly Sills, who in subsequent productions made the role of Baby Doe her own, credits the show with providing the first major launching pad of her career.

Latouche’s death robbed the musical theatre of what may have been three decades or more of new work, adding him to the sad pantheon of artists in his field who were constantly pushing the boundaries of the form with experimentation and creativity, from George Gershwin (dead at 37) to Howard Ashman (41, lyricist of Little Shop of Horrors and Beauty and the Beast) and Michael Bennett (44, creator of A Chorus Line and Dreamgirls.) Thus his story is in large measure a depressing saga, especially given the lyricist’s propensity for self-destruction.

Pollack vividly recounts Latouche’s hedonistic habits: “Drinking brandy or bourbon neat . . . chain smoking English Ovals, [he] frequently caroused till the early morning hours—dining out, attending parties, nightclubbing, playing bridge—after which he would sleep, in the nude as his preference, for a few hours, with perhaps a nap during the day, sometimes in his bathtub.” From a friend: “He would work and talk all day, and drink all night—at the same time dressing for dinner, donning a tux for a Harlem party, and following classical music, opera, and jazz.”

(Part of the reason for such endurance can be credited to Max Jacobson, aka Dr. Feelgood, whose potent injections of vitamins mixed with amphetamines affected—and often ruined—the lives of his patients who depended on them to stay awake, energetic, and creative well beyond the demands of their bodies. “Instant euphoria” was how the effect was tagged by Truman Capote, who was joined in his enthusiasm by a multitude of celebrities, including Mickey Mantle, Maria Callas, Elizabeth Taylor, Elvis Presley, and even JFK and Jackie.)

Latouche’s sexual magnetism was apparently potent. At a compact 5’3” and around 140 pounds, he was a fireplug of erotic charisma. Yul Brynner was a conquest, as well as (most likely) Gore Vidal, who sketched Latouche as a character in his novel, The Golden Age. But Latouche had frequent affairs with women as well; following in the footsteps of his pal Paul Bowles, he married a lesbian, Theodora Griffis, a relationship that was occasionally sexual but doomed to failure. The poet Kenward Elmslie, his longest-lasting relationship, was his partner when he died. But not everyone was charmed. Patricia Highsmith thought him “repellent,” and collaborators railed against his laziness, egotism, and stubbornness. Jean-Paul Sartre offered this pointed aperçu: “A tiny sedate gargoyle with a sick, brilliant mind: I liked him.”

But no one seems to have turned down an invitation to Touche’s parties. One of the pleasures of Pollack’s book is its dazzling cast. Latouche lived in the epicenter of a literary and theatrical vortex, and most everyone who was anyone made his or her way to his domain, whether it be in his Greenwich Village digs or later, in his East Side penthouse. Wandering in and out of Latouche’s life are Kurt Weill, George Balanchine. E.E. Cummings, John Ashberry, Dorothy Parker, Aaron Copeland, John Cage, Alexander Calder, W.H. Auden, Benjamin Britten, Gypsy Rose Lee, and even Eleanor Roosevelt.

One of his parties, chronicled by Kenward Elmslie, finds composer Ned Rorem lusting after a “top dollar” hustler, Lena Horne on Jane Bowles’ lap, Vernon Duke and Larry Rivers “making out in the john,” Marlene Dietrich reciting Rilke, and Virgil Thompson dancing with a lampshade on his head. Another gathering recounts a parlor game that asked each guest to describe their five best sexual experiences. While Tennessee Williams and Carol Channing dove right in, Eudora Welty quietly took her leave before she had to take a turn. Oh, to be a fly on the wall.

This is a gobstopper of a book, despite its subject’s short life—nearly five hundred densely packed pages, excluding voluminous notes. There is enough meticulous detail—if you ever wanted to know the acting roles Latouche played in high school, this is the place to come—to challenge the casual reader, and the prose is often more dutiful than delightful, but as a boon to historians and theatre fanatics it’s an invaluable resource. Each of Latouche’s works nudged or blatantly pushed the American musical into the maturity that began with the Rodgers and Hammerstein era, and through his rigorous intelligence and restless imagination created an impressive portfolio. As Pollack writes, had Latouche lived beyond his forty-one years, he…surely would have continued to produce works of daring and brilliance.” All credit to his biographer that he has brought forth a definitive guide to his accomplishments that is suffused with a melancholy conjecture of what might have been.

Michael Adams is a writer and editor living in New York City. He holds a PhD from Northwestern University in Performance Studies. His doctoral dissertation examined the lyrics of Stephen Sondheim.