Up With the Sun by Thomas Mallon

/Up With the Sun

by Thomas Mallon

Knopf, 2023

Meet the late Dick Kallman: Actor, singer, dancer, murder victim.

Prolific writer Thomas Mallon—11 novels since 1987, plus a hefty handful of non-fiction works—has made idiosyncratic historical fiction his métier. Two of his early novels were among my favorites of the ‘90s: Henry and Clara examines the sad fate of the couple assigned to share the box at Ford’s Theater with the Lincolns the night of the president’s assassination; Dewey Defeats Truman, set on Election Night 1948, captures the head rush—and ultimate dispirited letdown—of the citizens of Thomas Dewey’s Michigan hometown, after what seemed an inevitable triumph became a shocking reversal of fortune.

Mallon’s most celebrated work has been the 2008 Fellow Travelers, concerning a gay relationship between two Washington DC government employees struggling against the backdrop of Joseph McCarthy’s war against Communists and homosexuals. The book was adapted into an impressive opera and will have further life as a non-musical TV series streaming soon on your favorite device.

After fictive forays into goings-on in the Nixon, Reagan, and George W. Bush administrations (which I have not read), Mallon’s latest returns energetically to mid-century, using as his canvas the glittering, sordid landscape of Broadway and Hollywood from 1950 to the early ‘80s. Mallon has gleefully mined these worlds for sexual hijinks, naked ambition, narcissism, backstabbing, greed, and ultimately murder—both real and imagined. (In an Author’s Note, Mallon writes that many of the book’s details have been “considerably altered by the author’s imagination . . . Some of this novel’s characters never existed at all.”)

At the center is Dick Kallman, a real, once-promising but ill-fated stage, film, and TV performer, whose charming demeanor (he’s called “aggressively ingratiating”) and pleasant musical skills helped him rise above chorus-boy status, but not far enough above to please Kallman himself: stardom remained frustratingly out of reach.

There were small roles in Broadway musicals, a fair-to-middlin’ night club act, and a promising boost by Lucille Ball (herself enjoying something of a pop culture renaissance of late). Post I Love Lucy, Ball created and mentored a repertory company of promising young performers, including Kallman. None of them went on to lasting fame, but at least it won Kallman a prime-time sitcom (with a predictably asinine premise), cancelled after one season.

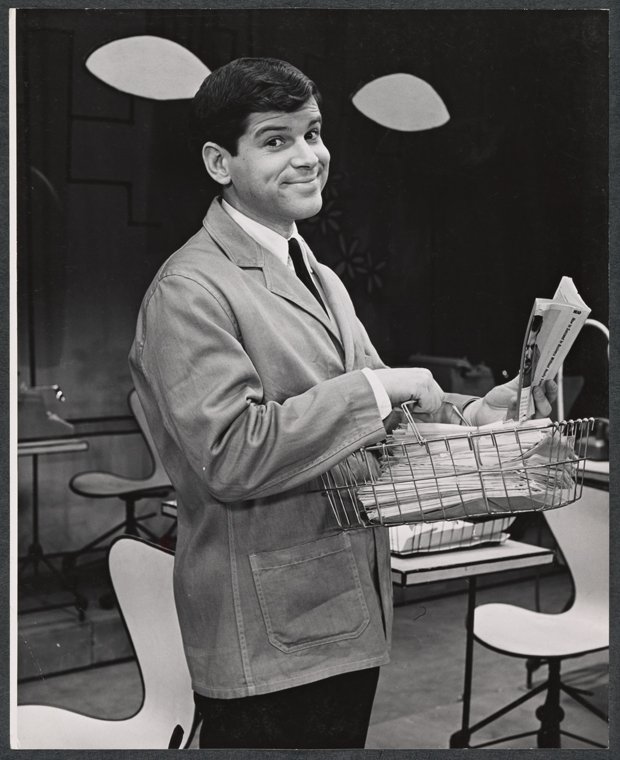

Broadway fame tantalized as well, when Kallman sought the lead in one of the era’s greatest successes, How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying. He lost the role to Robert Morse, whose career endured, albeit bumpily, for decades. Kallman had to settle for headlining the show on its first national tour. Ditto with Half a Sixpence, a modest hit on Broadway that Kallman headlined on the road. (I saw both, in Detroit, and vividly remember the shows, but not their star.)

When he finally faced the reality of his failing career, Kallman called on his entrepreneurial skills—plus a handy instinct for fine art and antiques—to begin anew as a private dealer based in his plush New York apartment. It’s there he met the grisly end that gives the book its momentum: shot to death, along with his lover.

Two alternating narrators tell the story: one takes us into in Kallman’s head, the other belongs to Matt, a Broadway pianist whose life dovetailed with Kallman’s, from the early 1950s, where they both worked in a flop musical, to the early 80s, when Matt becomes a fact witness to Kallman’s murder.

Dick Kallman in How To Succeed in Business Without Really Trying

Mallon seems to have been exhilarated with this sabbatical from the buttoned-up halls of DC and immersing himself for a time in the uninhibited raciness of showbiz. He excavates deeply into the mines of the lore. Real life cameos from celebrities—readers under 50 might wish for a glossary—give the book its pep. Those of us familiar with Kaye Ballard, Carole Cook, Mabel Mercer, Ted Hooks, Sophie Tucker, Janet Gaynor, Henry Willson, Earl Wilson, Jerry Zipkin, Dagmar, Pat Buckley, and more are rewarded with a nostalgic rush, many of whom prove the point that fame can be fleeting.

(Speaking of cameos, Mallon has slyly provided an Easter egg when Hawkins Fuller, a closeted—fictional—State Department official from Fellow Travelers makes a brief appearance to meet and flirt with our boy Dick. Whether they “tricked”—the word of choice for hooking up in that era—is left to the reader’s, and Mallon’s, imagination.)

Mallon also honors gay history with nods to historic events, including placing both Kallman and Matt in the audience of Carnegie Hall the night Judy Garland performed her legendary 1961 concert. Mallon makes the event a turning point for Kallman:

Every other seat seemed filled by the kind of old homo he’d seen sneaking into every Third Avenue bar since before the El came down... Two of them here had tears running down their faces. As everybody and his uncle knew, whatever was broken in these guys was reaching toward and sparking whatever was broken in her. He would never connect like that with an audience; he had sensed it all along, and come to know it in some hard, real way during the last few stalled years.

Speaking of gay icons, let’s hear it for the contributions of Dolores Gray—rich of voice, plain of face—and cherished since the early ‘50s, thanks mostly for her camp classic numbers in MGM musicals. She makes frequent contributions to the fun, not only as a walking punch line, but also as an enduring relic of the era. As Kallman’s latter day business partner in his commercial endeavors, Gray is perpetually snobbish, vain, over-costumed, and suspicious that his death will cheat her out of her financial due.

And then there’s Kallman, about whom almost no one in the book can find a positive word: “You’re trying to swim but feel yourself sinking and he’s the one with his hand on your head,” says one character. Another: “I’d never seen Dick be truly sincere about anything, and if he started now, I think it would have repulsed me.”

This blend fact and fiction leaves the reader tantalizing questions. Did Kallman take advantage of an heiress’s naiveté by cruelly using her as a beard? Did he sell out his friend and patron Lucille Ball by fabricating a lurid story and trading it to a gossip columnist to advance his career? Did his regular visits to an Episcopal priest and family friend for counseling usually end with oral sex as a therapeutic add-on?

Mallon’s attempts to mitigate Kallman’s bad behavior via an overbearing mother and society’s widespread homophobia soften him a bit, but he remains throughout a chap most would avoid at parties (Episcopal clergymen excepted).

Still, antiheroes can be fun, so by contrast Matt the pianist is something of a milquetoast, a useful tool to fill in the narrative gaps, and he’s carries the burden of the book’s latter half with the aftermath of the murders and the trials of the killers. These chapters are largely suspense-free and include the appearance of Devin, a former hooker with a heart of gold, who’s also an ace police informer and office dogsbody, who becomes Matt’s boyfriend and eventual caregiver. He seems grafted from another novel.

Mallon is a solidly conventional novelist, and the book is a pleasant read. But I couldn’t help but wish for something more sharp-edged, satiric, and sexier. (Paging Bruce Wagner and Paul Rudnick?) But it’s clearly the best (only) book we’re going to get on Dick Kallman in our lifetimes, and I take some comfort in imagining the joy it would bring him to have captured even a small portion of the spotlight—even if it comes four decades late and meant taking a bullet to the brain.

Michael Adams is a writer and editor living in New York City. He holds a PhD from Northwestern University in Performance Studies.