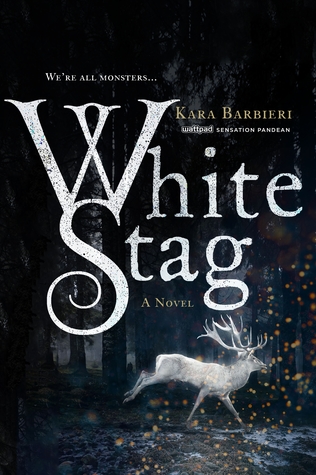

White Stag by Kara Barbieri

/White Stag

By Kara Barbieri

Wednesday Books, 2019

Kara Barbieri’s much-heralded debut YA novel White Stag opens with a veritable Mahler symphony of tinny, discordant notes. Right there on the cover, there’s the tag-line “We’re all monsters …” Tag-lines have a dirty, economical work to do, admittedly, but this one seems a bit finger-pointy; there’s an encouragingly high likelihood that most of the book’s readers won’t, in fact, be monsters. Also on the cover: a quick term identifying the author as a “Wattpad sensation” who goes under the pen-name Pandean. On the surface, this might not seem foreboding; Wattpad is, after all, a communal story-sharing website that gives millions of writers not only a forum for publication but access to the support and feedback of however large an audience their work can garner. Working under the name Pandean, Barbieri has amassed an enormous audience of loyal readers who’ve been following the twists and turns of her high fantasy story for years.

Underneath that surface, the worries are obvious: Wattpad is an enthusiastic rather than a critical environment, one in which writers can grow enormously popular without ever having their shortcomings even noticed, much less challenged. By the site’s very nature, it promotes serialized what-happens-next storytelling over carefully constructed plots. And any “Wattpad sensation” who comes to the notice of a mainstream publisher will have done so on the basis of the size of their following, which is hardly an incentive for stem-to-stern editing, even if it’s badly needed. In other words, long before she got a deal with Wednesday Books, Barbieri was accustomed to complete editorial control of her fiction. This is seldom healthy for authors (in her Acknowledgments, Barbieri thanks somebody named Ashleigh “who worked so hard to show the world how wonderful White Stag is;” if the author does say so herself).

Things get worse, as they invariably do, in the Author’s Note (will 2019 be the year when the publishing world finally abolishes this attempt by writers to eat their cake and have it too? We can only hope), which opens with the line “there is truth in fiction” despite the fact that a) this is a pompous truism that’s been known for 7000 years, and b) the author is just an eeensy bit young to be pontificating. This tone continues with “trigger warnings”: White Stag is at times a dark and violent book, and as is now typical in the YA genre, the author feels compelled to apologize for that fact:

There is content in this book that may trigger you. If it does happen, I want you to know that your feelings and experiences are valid and your safety (both physically and mentally) matters more than anything else. My experience is not yours, and I would always advocate for you to do what is best for you. If that means putting the book down, then I want you to know it’s okay and I understand.

This underscores how deeply, impenetrably odd “trigger warnings” are; in what other era have writers felt the need to warn readers that their prose might actually be effective in evoking emotional responses? This, plus the author’s identification of her own personal traumas with those of her main character, gives the book a clinical air, like you’re reading a self-diagnostic chart rather than a debut novel. Freighted right at the beginning of a book that’s already called its readers monsters, all of this combines to form the novel equivalent of the “Keep Out” sign adolescents put on their bedroom doors.

If you ignore all of that, if you know nothing about Wattpad or its sensations, don’t consider yourself a monster, and aren’t put off by the author’s warning that some of her prose might be effective, if you venture into White Stag and actually read it, you’ll be glad you did, but that’s a lot of ‘if’s.

This is the story of a young woman named Janneke, a strong, resourceful teenager who’s already proficient at tracking and killing game when her village is attacked and she herself is abducted to the Permafrost, the realm of quasi-immortal goblins who hate humanity but sometimes traffic in it just the same:

There were a few fates for humans in the Permafrost. Some ultimately died here, human until their last breath; sometimes thralls were released on their goblin captor’s death; and sometimes they stayed under the new lord who replaced them, depending on the binding spell holding them to the Permafrost and the will of the late lord. And sometimes … sometimes those who had certain desirable skills or traits, who were able to biologically adapt to the Permafrost, those who had a close camaraderie of sorts with the lord they served, who were judged as a good addition to the species … they changed. From rituals, time spent immersed in goblin culture, and the slow biological evolution of their human bodies went through, those humans became goblins eventually. Changelings.

When White Stag opens, Janneke has been in the Permafrost for almost a century as thrall to a powerful, magnetic goblin prince named Soren, with whom Janneke has a jagged, complicated relationship. Early on in the book, he impatiently reminds her that she’s more than just a thrall, that he also considers her his close friend. But he’s overwhelmingly more powerful than she is, and he and all of goblinkind are fundamentally alien to her human heritage, alien and hostile. One of the most palpable tensions running through the book is that purely personal one: Janneke constantly reminding herself that goblins are crude, violent creatures, with the reminders being more urgent because slowly, terrifyingly, Janneke feels the Permafrost working on her, changing her, gradually warping her into a goblin. She might tell herself that she was only aligning herself with the world of her thralldom, but her own internal denials are increasingly desperate:

But adapting wasn’t the same as truly becoming like them. It couldn’t be. I wasn’t a monster. I wasn’t about to become a monster with a mind so twisted that emotions were foreign, and brining pain caused pleasure - all the things my father had taught me to hate since I was the height of his knee.

Barbieri takes these two intertwining tensions and heightens them with an expert ear for pacing that was almost certainly sharpened by all of her experience on Wattpad. White Stag is thrilling and sharply complex throughout, exactly the kind of fiction debut that makes a reader eager to see everything else the author will write. Readers warned off by that “trigger warning” will miss a truly auspicious start to a career beyond the fields of the Internet.

—Steve Donoghue was a founding editor of Open Letters Monthly. His book criticism has appeared in the Boston Globe, the Wall Street Journal, The Spectator, and the American Conservative. He writes regularly for the National, the Washington Post, the Vineyard Gazette, and the Christian Science Monitor. His website is http://www.stevedonoghue.com.