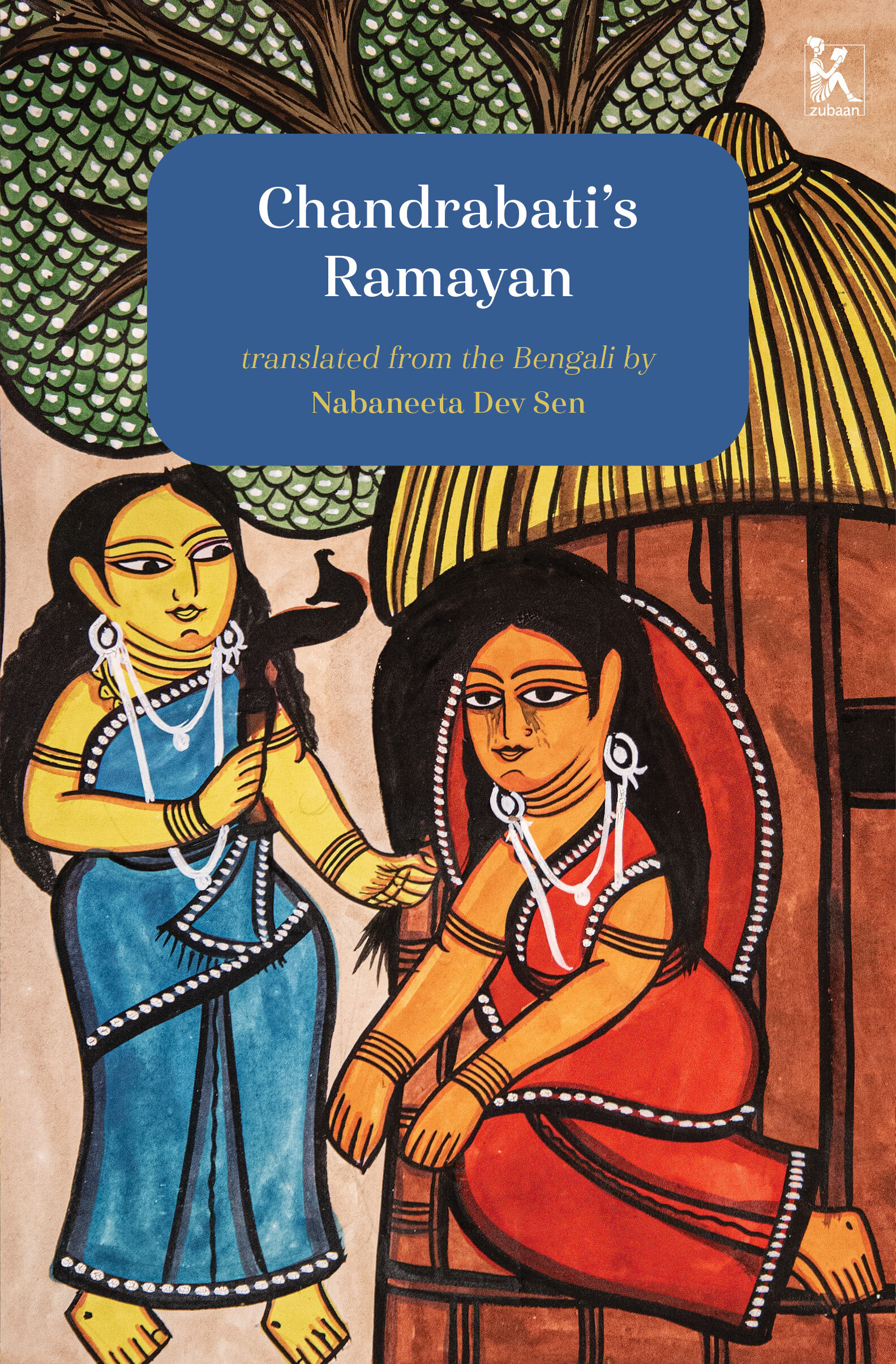

Chandrabati's Ramayan

/Chandrabati’s Ramayan

Translated from Bengali by Nabaneeta Dev Sen

Zubaan Books, 2020

Chandrabati’s Ramayan is a retelling of the Hindu epic, Ramayana, from the perspective of Sita, the wife of the hero, Ram. Chandrabati, a 16th-century poet who lived in what is now Bangladesh, allows Sita, generally portrayed as the ideal of chastity and obedience, to have her own space to lament the tragedies that haunt her life. Chandrabati wrote for a non-courtly audience, thereby bringing the revered epic, written in a distant, sanctified Sanskrit, closer to the masses. Chandrabati’s version of Ramayana, perhaps fittingly, is sung even today by peasant women in Bangladesh.

Other than being widely considered the first female Bengali poet, little else is known about Chandrabati. Even the peasant women who have sung her songs over the years have never heard of her. The translator of this present volume, Nabaneeta Dev Sen, re-discovered her work while digging around for research on village women’s Ramayan songs. Though the accepted version of Ramayana is the one written by the ancient poet Valmiki, scholars claim that there are at least 300 versions. These exist as folklore or as part of regional literature and are not accorded much religious significance.

Chandrabati’s Ramayan earns a significance of its own, performing the radical act of loosening the characters from their epic trappings and re-telling the story with entirely human characters who are dealing with and lamenting the injustices brought upon by their destiny. The Sita of Ramayana, though a goddess incarnate, is widely regarded as the major symbol of chastity and subservience. Valmiki claimed that one of his main objectives for the epic was to showcase the greatness of Sita. Chandrabati’s Sita, shorn of her epic character, is portrayed with the sensitivity and understanding that comes from being a woman in a man’s world. Chandrabati writes that Sita is destined to be miserable all her life. Sita gets exiled along with her husband, gets kidnapped by a demon king and finally, is made to go through an Agni Pariksha (a trial by fire) by her husband, who places his own honor above his love for her. While the epic, true to its genre, describes the valiant exploits of Ram and the “greatness” of Sita, unshaken, while facing the terrible trials of her life, Chandrabati writes as though she is lamenting for a woman she intimately knows, like a daughter or a sister. Chandrabati is not interested in greatness, but instead shows that even gods, when incarnated as humans, do not have an escape from human misery.

The second part of the poem adopts the style of a Baromasi, which were poems composed and sung by women all over north India. These songs articulated the female experience by associating it with the different seasons of the years. The reigning theme was of the pain and suffering that was inevitably part of being a woman. By writing in the Baromasi style, Chandrabati successfully transforms Sita into the everywoman – the representative of womanhood in India, rather that of the unattainable womanhood codified in the epics.

Chandrabati’s Ramayan goes as far as to criticize Ram for his actions, which is very rare among the over 300 versions of the Ramayana that exist. When Ram decides to exile Sita, doubting her faithfulness to him, Chandrabati’s words bristle with rage:

As forests burn with wild fires,

As rivers overflow with floods,

Ram raged wild, insane,

Eyes hibiscus red, blood rushed to Ram’s temples,

Nostrils breathed fire, the crown of his head was about to crack.

In the fire that Kukuya had kindled that day,

Sitadevi would burn along with Ram

And the city of Ayodhya would burn as well,

Abandoned by Lakshmi the kingdom would be destroyed

Paying heed to others’ words lead to your own destruction.

Chandrabati says, poor Ram, you have totally lost your mind.

Chandrabati’s Ramayan performs many subversions at once. By comparing the goddess with the everyday woman, it problematizes the status of women in India. With that, this story about articulating Sita’s misery also becomes a representation of solidarity and power, a song that allows women to communicate and find community across the barriers of time and place.

Lakshmi Ajikumar is a PhD student in women's writing living in Chennai, India.