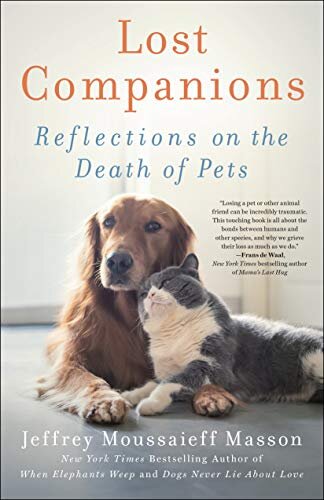

Lost Companions by Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson

/Lost Companions: Reflections on the Death of Pets

By Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson

St. Martin’s Press, 2020

It’s such an easy and banal thing to write sentimentally about the death of beloved pets that you marvel it took Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson so long to devote a book to the subject. Beginning in 1994 with When Elephants Weep (written with Susan McCarthy) and progressing on through such books as Dogs Never Lie About Love, The Pit Who Sang to the Moon, and The Nine Emotional Lives of Cats, Masson has sold millions of copies of books specifically dealing with the emotional side of the human-nonhuman connection, and no aspect of that connection is more emotional than the end of it.

Humans have been memorializing this particular trauma for millennia (an ancient Roman tomb inscription read, “I am in tears carrying you to your final resting place as much as I rejoiced bringing you home in my hands 15 years ago”), always noting, with seemingly evergreen wonder, that the pain of grief in such moments is often as intense as anything humans feel when mourning their own kind.

Masson’s animal-emotion books are downright radioactive with evergreen wonder, the perpetual astonishment of a human encountering trademarked “human” emotions in non-human animals. And simple math suggests that his books have awakened this sense of wonder in a core audience of readers who previously thought non-human animals were Cartesian flesh-robots with no feelings of any kind. The persistence of this bloc is puzzling, since billions of humans have had pets in the last 150 million years, and virtually every human who has ever had a pet knows that they aren’t unfeeling wind-up toys. But given the fact that millions of chickens, cows, pigs, dogs, and other animals are still farmed in horrific conditions for food all over the world, every reminder of this kind is probably doing the work of the angels.

When it comes to writing about animals, Masson isn’t a particularly deep thinker, and Lost Companions is a good example. “There is no greater challenge than facing the death of a beloved intimate,” he writes at one point, “whether it be your mother or father, your child, your friend, your spouse, or the animal you have come to love like any member of the family.” As a premise, it’s tough to argue with something like this.

Argument is of course not the point in any Masson book; these are books about connection, not contention. Masson has here assembled anecdotes from people who’ve experienced the loss of beloved pets - not just dogs and cats, but also horses, birds, and even an enormous crocodilian - and he layers out those anecdotes with his own anodyne observations, which more often than not take maddeningly circular shapes - “some say this, others say that, and this may be good, or it may be bad,” and so on, as when he talks about euthanizing a dying pet:

I just do not see myself putting [his beloved dog] Benjy’s head into my lap, watch him look up at me with complete trust, and then nod to the vet to go ahead and give him the final injection. I just don’t see how I can stand it. It is not for me like a dear relative who has begged you to do just that. He is a dog who cannot consent. The decision must be mine and I just cannot be sure what he would say if he could. Maybe, yes, he would say the time has come. But maybe, too, he would beg me to wait just one more day, or one more week. Maybe, he, too, envisages simply not waking up and would, just like me, much prefer that. I am just a little bit uncomfortable with how easy it seems to some to take a dog or cat for a final vet visit. I say some, because I realize that for most people this is one of the most difficult decisions of their life. There are times when it is selfish to do it and others when it is selfish not to do it.

This is meant to be comforting, surely, although it’s difficult to imagine any dog or cat owner finding it “easy” to take their pet to that final vet visit. The moment is entirely harrowing: you are ending your friend’s life because you cannot solve their suffering, and you know what you’re doing but, as Masson points out, they don’t. There are no ethical escapes from the process - you can’t let them suffer any longer, particularly not in a selfish search for some statistically-unlikely “dying in their sleep” scenario, so you have no choice but to bundle them into a car and pay a professional to give them a quick, painless death. And the desolation of the moment after is public - you must stagger back through the waiting room and back into the day’s sunlight, feeling certain that the amputation is visible to everybody. And when you get back home, the food bowls are still there, the toys are still there, and the memories are still echoing everywhere.

Lost Companions will bring that process and all the attendant emotional states before the reader in dozens of incarnations, dozens of moments that will strike all of those readers as devastatingly recognizable. It’s not the first book of its kind, obviously, but it might reach a larger audience than any of the others - and it’s bound to comfort them.

—Steve Donoghue is a founding editor of Open Letters Monthly. His book criticism has appeared in The Boston Globe, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, and The American Conservative. He writes regularly for The National, The Vineyard Gazette, and The Christian Science Monitor. His website is http://www.stevedonoghue.com.