No More Giants

/Sondheim: Lyrics

By Stephen Sondheim

Edited by Peter Gethers and Russell Perreault

In March, Stephen Sondheim turned 90. Time was, this would have been an occasion for a big-ticket, star-studded tribute. But with a (we hope) temporary hold on public events, the celebration became a two-hour-plus streamed concert in a benefit for the Actors Fund: dozens of Broadway performers singing from their homes in casual clothes, with spare musical accompaniment, but blessed with an intimacy impossible to achieve In Carnegie or Avery Fisher Hall. The event was low-key, affectionate; celebratory, yes, but often elegiac, especially when some of his best songs melded with our current reality: “Take Me to the World.” “Not While I’m Around.” “No One Is Alone.”

And, here, “No More” from Into the Woods, where a distraught, emotionally destroyed fairy tale Baker confronts the despair of the unexpected and random loss inflicted upon his world:

No more giants,

Waging war.

Can’t we just pursue our lives,

With our children and our wives?

Till that happier day arrives,

How do you ignore

All the witches,

All the curses,

All the wolves, all the lies.

The false hopes, the goodbye, the reverses,

All the wondering what even worse is

Still in store?All the children . . .

All the giants . . .

No more.

In his nearly 70 years working in the theater, Sondheim has won 8 Tonys, 8 Grammys, a Pulitzer Prize, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, a Kennedy Center Honor, a perch the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and even an eponymous Broadway theater—an honor accorded to very few living figures. (And for those who chart such things, he’s a GOT, missing only an (E)mmy to achieve that much-coveted status.)

At the time of the New York pandemic shutdown, a revival of his first success, the 1957 West Side Story (his lyrics wed to Leonard Bernstein’s music), Dutch director Ivo von Hove reimagined the musical for Broadway in a radicalized, controversial video-driven version. A gender-bending “revisal” of his Company—the male protagonist Bobby of 1970 becoming Bobbie in 2020—was set to open on his birthday after a successful run in London. Both productions are in limbo as theaters remain dark. Still to come—but when?—is a reimagined film version of West Side Story (the first received the Oscar for Best Picture in 1961) from the fertile minds of Tony Kushner and Steven Spielberg. There are whispers of a film version of the 1973 Follies, and film director Richard Linklater has presumably begun the astonishingly formidable task of bringing the 1980 Merrily We Roll Along to the screen—a 20-year project. Since the musical unfolds backwards in time, with characters middle-aged at the beginning and young adults at the end, Linklater intends to capture the actors as they age over the next two decades. (Somebody please send me a note in the afterlife to see how that one fares.) A high-powered revival of Sunday in the Park With George, starring Jake Gyllenhaal and Annaleigh Ashford, sold out its run in New York three years ago and was set for a London stint this summer; that too has an uncertain future.

And oh yes, the books: two hefty collections of his complete lyrics—Finishing the Hat (2010) and Look, I Made a Hat (2011), with exhaustive annotations and directives by their creator that have rightly been heralded as among the most important theater texts of the modern era.

His work has also seeped into pop culture via recent films: characters singing impromptu versions of two songs from Company in The Marriage Story; a few bars of “Losing My Mind” sung by Daniel Craig in Knives Out; and “Send in the Clowns” adding an additional layer of creepy to The Joker, as sung by drunken Wall Street bros on the subway.

And now this, a tidy compendium of some of his best lyrics in one of Everyman’s Library Pocket Poets series—handsomely designed, adorned, as is custom, with a ribbon bookmark. With this inclusion, Sondheim shares the Everyman shelf with Dickinson, Stevens, Yeats, Byron, and dozens of others of singular and proven merit. (The only other contemporary songwriter so honored—so far—is Leonard Cohen.)

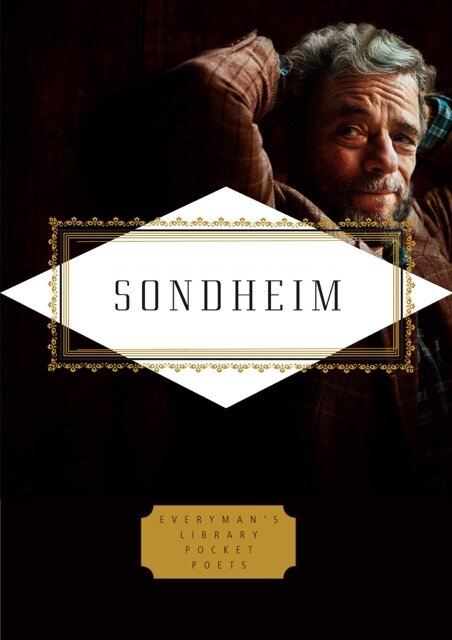

I like to imagine that Sondheim’s reaction when he was told of this project fairly mirrors his front cover photo. Whereas the back cover shows him in his late 20s—brash, confident, a bit cocky—on the other side is Sondheim as graybeard—weathered and wrinkled, scowling, a skeptical eyebrow. Biblical prophets were cheerier. For he has always resolutely insisted that song lyrics are not poetry, nor should the two be confused. “Lyrics, even poetic ones, are not poems,” Sondheim writes in Finishing the Hat. “Poems are written to be read, silently or aloud, not sung.”

Case closed? Not for Peter Gethers, the editor of the Hat books, as well as this new volume. In his introduction, he takes us to the OED: “A piece of writing in which the expression of feelings and ideas is given intensity by particular attention to diction (sometimes involving rhyme), rhythm, and imagery.” On the other hand, bolstering Sondheim’s point, there’s this from Robert Gottlieb and Robert Kimball, who co-edited Reading Lyrics in 2000, an anthology of American song lyrics: “Reading song lyrics is very different from reading poems. A lyric is one-half of a work and its success or failure depends not only on its own merits as verse but on its relationship to its music.”

Just so. This is an issue about which reasonable people can disagree. Whether you can hum the music that supports these words as you peruse the printed lyrics or instead simply appreciate the words themselves, you’re most likely in for a treat.

In the good ol’ days, musical theater lyricists—Oscar Hammerstein II, Lorenz Hart, Frank Loesser among them—were memorialized and glorified with gorgeous coffee table tomes (the best of them by Knopf), stuffed with every lyric from every production, as well as unpublished songs, annotations, and historic photographs; truly essential cultural endeavors. Cole Porter was the first to be so celebrated, in 1983, his with a forward by John Updike. (Porter was also rewarded in 2006 with his own mini by the Library of America, a petite volume stuffed with his smart, effervescent lyrics.)

Of late the mission to memorialize these great works has slowed and shrunk, with only Oxford’s Alan Jay Lerner volume to add to the list—most welcome. but decidedly down market in size and extras compared to its predecessors. Hopefully, the work of Sheldon Harnick, Dorothy Fields, and E.Y. Harburg are waiting in the celestial wings for their own deluxe treatments, but hopes are slim that they’ll be treated as extravagantly. (Of course, pop/folk/rock/rap songwriters are well-represented in print: you can study the complete works of the Beatles, Joni Mitchell, Patti Smith, Bernie Taupin, Paul Simon, Jay-Z, etc. in beautifully designed hardbound tomes that treat them as poetry. Lyrics as literature? Just ask Bob Dylan.)

This volume is a Whitman’s Sampler, a tasty selection drawn from almost every one of Sondheim’s projects, from his first, Saturday Night, written in the early 50s but unproduced in New York until decades later, to his much fussed over, revised, and irritatingly retitled and retitled and retitled again take on Wilson and Addison Mizner—finally unveiled as Road Show in 2008. There’s one from the TV show, Evening Primrose and two from the film Dick Tracy. (Missing is his song from the Warren Beatty film Reds, the exquisite “Goodbye for Now,” and “I Never Do Anything Twice,” from the 1976 film The Seven Percent Solution, a minor masterpiece of dirty innuendo (see below).

Gethers offers no explanation or annotation for his choices, thereby opening the floodgates to the likes of me and other Steveadores (yes, it’s a thing; better than Sondheimites) to question, criticize, argue, and second guess. As for my opinion (thanks for asking), I applaud the inclusion of unquestionable masterpieces: “The Miller’s Son,” “Marry Me a Little,” “The Road You Didn’t Take,” “A Little Priest,” “A Bowler Hat,” and perhaps his greatest song, “Finishing the Hat, “ the subject of a recent PBS episode of “Poetry in America,” where actors and scholars dissected its form and content. In it, the painter George Seurat wrestles with his dual passions, as creator and lover:

And when the woman that you wanted goes,

You can say to yourself, “Well I give what I give.”

But the woman who won’t wait for you knows

That however you live,

There’s a part of you always standing by,

Mapping out the sky,

Finishing a hat,

Starting on a hat,

Finishing a hat . . .

Look, I made a hat

Where there never was a hat.

And I’d wonder at the inclusion of three songs from “Do I Hear a Waltz,” written with Richard Rodgers, from a musical Sondheim shrugs off as a wasted year of his life. And why the version of “Putting It Together” written for a Streisand album instead of the original? And why not at least one of the extended “one-act play” songs: “Chrysanthemum Tea,” from Pacific Overtures; “A Weekend in the Country” from A Little Night Music; “Barcelona” from Company; “Franklin Shepherd Inc.” from Merrily We Roll Along? And I miss “Take Me to the World,” “Love I Hear,” “Now You Know,” “Take Me to the World.” And one more: an enthusiastic vote for “I Never Do Anything Twice,” in which an old Edwardian bawd asserts her predilection for sexual diversity. The litany of her lovers includes this saucy genuflection to a member of the clergy:

And then there was the Abbot

Who worshipped at my feet

And who dressed me in a wimple and in veils.

He made a proposition

(Which I found rather sweet)

And handed me a hammer and some nailsIn time we lay contented,

And he began again

By fingering the beads around our waists.

I whispered to him then

“We’ll have to say Amen.”

For I had developed more catholic tastes.”Once, yes, once for a lark.

Twice, though, loses the spark.

As I said to the Abbot,

“I’ll get in the habit,

But not in the habit.”

You’ve my highest regard

And I know that it’s hard—

Still, no matter the vice

I never do anything twice.Unless . . .

No, I never do anything twice.

But in the main, Gethers selections are unimpeachable, even when provocative. He and Everyman have given us fans and fanatics an early stocking stuffer, a parlor game prompt, a primer for the uninitiated, and a splendid birthday gift to the still-vital nonagenarian. Not to mention a cultural benediction bestowed on very few in the musical theater—whether he likes it or not. As Gethers writes, the lyrics within “can only belong to the genius, demons, love, and yes, poetry that all live inside Stephen Sondheim.”

And the old bawd says, Amen.

—Michael Adams is a writer and editor living in New York City. He holds a PhD from Northwestern University in Performance Studies. His doctoral dissertation examined the lyrics of Stephen Sondheim.