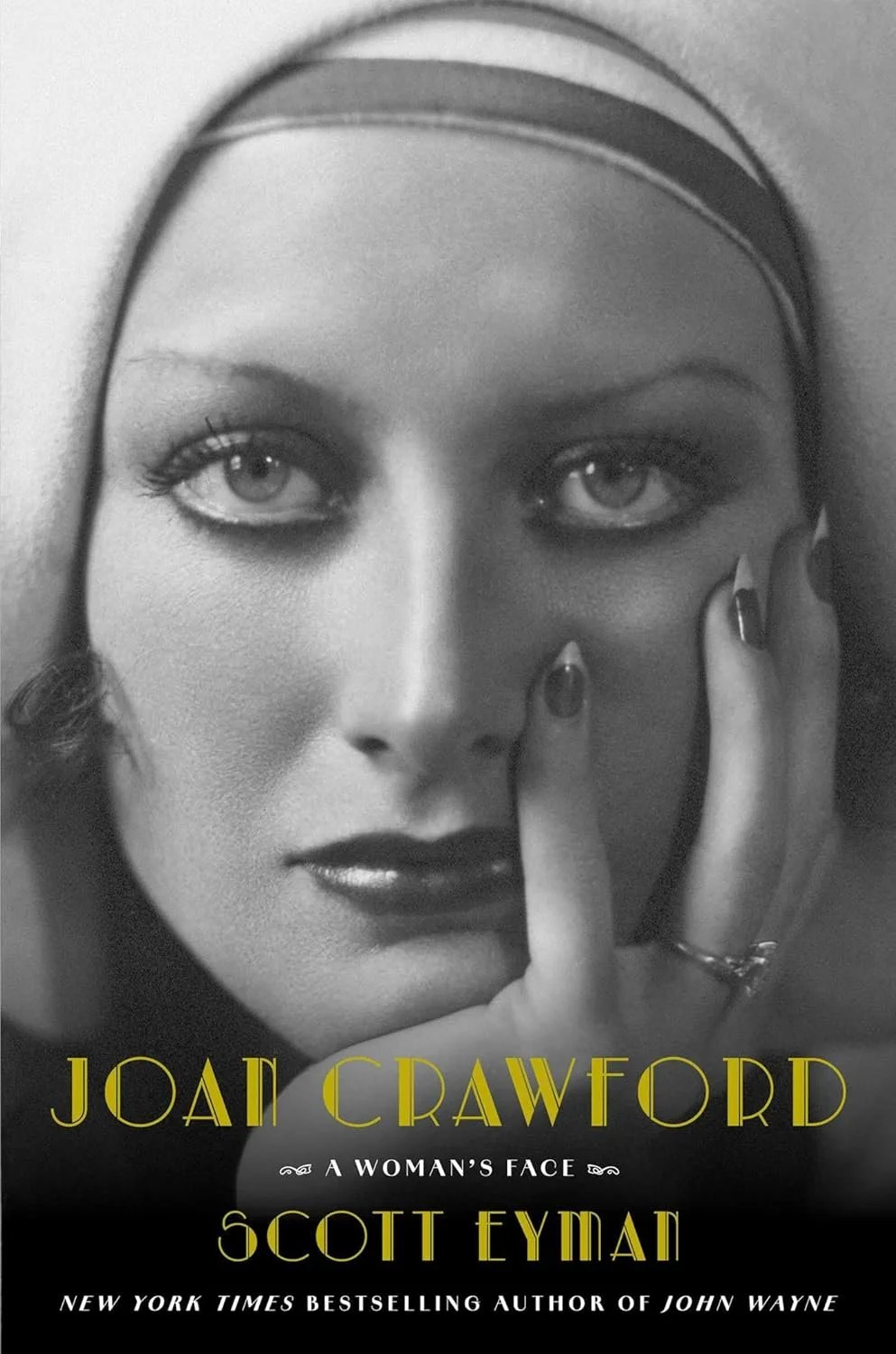

Joan Crawford: A Woman's Face by Scott Eyman

/Joan Crawford: A Woman’s Face

by Scott Eyman

Simon & Schuster, 2025

“When the makeup comes off for the last time, what’s left?” This question, posed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz upon Joan Crawford’s forced retirement from PepsiCo’s board of directors in 1973, brings the central concern of Joan Crawford: A Woman’s Face, Scott Eyman’s latest book, into sharp focus. For veteran Hollywood biographer Eyman, what’s left is a consummate professional who deserves to be known as much for her strategic self-invention as her unwavering loyalties and legendary hospitality.

Rigorous research, driven by the author’s own “mosaic of documentation and memory” as well as new archival material provided by the actor’s estate and grandson Casey LaLonde, informs Eyman’s treatment of Crawford. Eyman offers glimpses into the private world of a woman who pulled herself out of poverty to experience a great many loves in her lifetime, whether they be her passionate love affairs with movies, fashion, or men, including her well-known tryst with Clark Gable and her newly exposed relationship with the married newspaper publisher Charles McCabe.

Of the many biographies that have been written about Crawford, what stands out about Eyman’s treatment is its vast cast of characters. Joan Crawford reads like a people- rather than performance-first biography: a treatment that is refreshing on the one hand for its tight yet detailed portraits of major and minor figures in her orbit, but slightly unsatisfying on the other due to its uneven pacing. Crawford’s four husbands (actors Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Franchot Tone, Philip Terry, and Pepsi-Cola chairman Al Steele) are naturally featured, but their presence never assumes dominance over the narrative. One of Eyman’s strengths is the attention he pays to the other confidants, colleagues, and creative luminaries in Crawford’s life, including figures such as actors Myrna Loy and Barbara Stanwyck, interior designer extraordinaire Billy Haines, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer costume designer Adrian, and producer Paul Bern. A perhaps unexpected yet greatly warranted appearance is Disney artist Mary Blair. Blair, who produced concept art for animated films including Saludos Amigos (1942) and Cinderella (1950), is best known today as the designer of the “It’s a Small World” theme park attraction. What is not often cited in stories told about Blair or Crawford is the connection between them: it was Crawford who ultimately urged Pepsi to sponsor the project for the 1964 World’s Fair, creating the conditions to cement Blair’s status as a Disney Legend.

Readers may wish certain productions were discussed more evenly or in more detail. In addition to Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962), a film Eyman describes as “often imitated, never duplicated,” one key exception is his kaleidoscopic coverage of the production of George Cukor’s 1939 film The Women. While even new generations of movie enthusiasts are quick to recall Crawford’s rivalry with Bette Davis (thanks, in part, to the first season of the series Feud), she was also fiercely competitive with Norma Shearer, the queen of the MGM lot and widow of “boy genius” producer Irving Thalberg. Crawford’s casting in The Women, for instance, “inevitably watered down Shearer’s dominance,” and Shearer ultimately granted Crawford, as well as Rosalind Russell, co-star billing. Eyman also recalls the moment when Shearer, arriving for the first day of shooting, finds that Crawford, like a chess player attempting to control the board, had rearranged the co-stars' trailers to position her own ahead of Shearer’s.

While Eyman addresses these famous feuds in detail, his tone tends not to read as gossipy tabloid fodder. Further, while audiences might have assumed that an aging Crawford was pathologically jealous of pretty, young actresses making their big breaks, she demonstrated a sincere capacity for mentorship. Take, for example, her support of Warner Bros. contract player Eleanor Parker: by recommending the young actor pursue a role in the John Cromwell film Caged (1950), Crawford opened the door for Parker’s first Oscar nomination.

The biography’s choppy transitions may prompt readers to savor this biography, pausing between its anecdotes and slowly consuming its profiles in bits and pieces. One of the more questionable examples of authorial whiplash comes from Eyman’s pivot from a discussion of Franchot Tone as an outdoorsman with left-wing inclinations who shared with his future wife a serious dedication to his career to the writer Budd Schulberg. Schulberg, author of the Hollywood novel What Makes Sammy Run?, wrote for The Hollywood Reporter that Crawford was nothing short of “sex at the ready.” Schulberg’s coverage, like Eyman’s, does not reduce its subject to her beauty or sex appeal. Rather, both encapsulate the notion that when it comes to Crawford, “it was not the physical but the mental power that came through, the mind of a superachiever.”

Eyman thus presents a sympathetic portrait of a star intended to right the wrongs done to Crawford with the publication of Mommie Dearest, the 1978 memoir written by her daughter Christina, which “created an entirely new narrative” that ultimately “made her a camp joke.” Even readers who begin skeptical of Crawford’s talent will likely find themselves persuaded by Eyman’s account of her relentless work ethic, devotion to honing her craft, and deliberate evolution of her personal brand. While Eyman gently pushes back to recognize MGM’s role in the matter, the screenwriter Frederica Sagor Maas sums up Crawford’s commitment perfectly: “No one decided to make Joan Crawford a star. Joan Crawford became a star because Joan Crawford decided to become a star.” Almost fifty years after her death, a star she remains.

Gabrielle Stecher Woodward writes essays and criticism on the stories we tell about creative women. Her book reviews have appeared in publications including Harvard Review, American Book Review, and Necessary Fiction. Explore her portfolio at www.gabriellestecher.com.